2025-01-31 09:26:00 Fri ET

treasury deficit debt employment inflation interest rate macrofinance fiscal stimulus economic growth fiscal budget public finance treasury bond treasury yield sovereign debt sovereign wealth fund tax cuts government expenditures

In the broader context of economic statecraft, we delve into the current homeland industrial policy stance worldwide. This homeland industrial policy stance tends to tilt toward substantially improving the worldwide resilience of global supply chains for critical technological advancements such as 5G high-speed broadband telecom networks, semiconductor microchips, and artificial intelligence (AI) applications in health care, education, defense, social security, trade, finance, and technology. In support of significantly less wealth and income inequality, these macro trends help promote greater economic growth, employment, price stability, and robust macro-financial asset market valuation.

At the heart of the homeland economic science is the key idea that the government should reduce risks to the domestic economy due to many vagaries of free markets, unpredictable shocks such as the Covid pandemic crisis of 2020-2022 and Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, and key punitive sanctions of geopolitical opponents such as tariffs, quotas, and even embargoes. Several supporters and proponents argue that this homeland industrial policy stance helps reshape a safer, fairer, and greener world. However, a deeper analysis of fundamental forces shows that this current homeland industrial policy stance may lead to the opposite macro scenario with adverse consequences. These consequences manifest in the common forms of trade wars, fragile supply chains, efficiency losses due to fair trade protectionism, and short-run price pressures and energy shortages in light of geopolitical tensions. In essence, the current homeland industrial policy redivides the world into the U.S. and its western allies versus their trade rivals: Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. In response to the Russian invasion of Ukraine and another dual conflict between Israel and Hamas and the Palestinians, the U.S. and western allies impose severe sanctions to significantly weaken the worldwide networks of both trade and finance with Russia. At the same time, the U.S. and western allies introduce tariffs, foreign investment restrictions, embargoes, and many other trade penalties on China, Iran, and North Korea. All these economic efforts help global trade partners and western allies better align with the current world order of U.S. democratic rules, regulations, and institutions from the World Bank and International Monetary Fund (IMF) to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and World Health Organization (WHO). The new world order of fair trade helps key western governments accomplish non-economic policy goals such as national security, technological dominance, and global peace and prosperity in Eastern Europe, Middle East, and the Asia-Pacific region.

The new homeland industrial policy stance is a complex and rational response to 4 major external shocks. First, the world economy has increasingly become a new global fair-trade system that emphasizes macro-financial resilience over economic growth. If the U.S. subprime mortgage debacle and Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 broke confidence in the traditional model of economic world order, the global recession of 2020-2022 sealed the deal. During the pandemic years, global supply chains buckled and exacerbated world inflation by raising the costs of both imports and energy resources (such as oil and natural gas). A global system that had once seemed to deliver steady flows of efficiency gains turned into a fundamental source of macro-financial instability. The pandemic crisis encouraged people to believe in the economic power of more government intervention in global trade, finance, and technology.

Second, geopolitical tensions escalated into the Russia-Ukraine war and another dual war between Israel and Hamas and the Palestinians. In response to Russian aggression, the U.S. and western allies introduced economic sanctions through all worldwide networks of trade and finance against Russia. To the extent that Russia launched the biggest land war in Europe since 1945, several free trade advocates gave up the empty promise that economic integration would ensure regional peace and prosperity. In recent years, China and America continued to spar with greater ferocity and hostility in their zero-sum trade war. Specifically, the U.S. government unilaterally imposed on China a wide variety of hefty tariffs, embargoes, investment restrictions, and several other non-economic penalties and sanctions in support of the lofty cause of fair trade.

Third, global energy shortages emerged as another major shock. Vladimir Putin’s weaponization of Russia’s hydrocarbon resources has inexorably convinced many politicians that they should secure alternative energy supplies elsewhere. This idea would apply to not only alternative energy supplies worldwide, but also alternative strategic commodities more broadly, such as rare earths, uranium ores, and lithium mines. In addition, the current war between Israel and Hamas and the Palestinians exacerbated hefty price hikes, shortages, and bottlenecks in global supply chains and traditional energy resources, especially oil, coal, and natural gas.

Fourth, the widespread adoption of generative AI, or Gen AI, software applications might displace many knowledge workers worldwide. This new macro shock seems to compound the sense that the new economy outpaces the average person in the high-tech marathon. By historical standards, the current Gen AI revolution seems to exacerbate social disparities in both wealth and income in many rich and middle-income countries.

The brand-new homeland industrial policy stance tends to tilt toward substantially improving the worldwide resilience of global supply chains for critical technological advances (such as semiconductor microchips, 5G high-speed broadband telecom networks, and Gen AI software applications in health care, defense, social security, education, trade, finance, and so on). Drawing on the European experience of the 1950s and 1960s, many governments now hope to build up national champions in strategic industries in support of electric vehicles (EV), semiconductor microchips, Gen AI software applications, tools, robots, avatars, and virtual assistants. These governments apply huge subsidies and domestic-content rules and regulations to encourage production at home. Western governments seek to leverage economic policy instruments to weaken geopolitical adversaries. These instruments include hefty tariffs, embargoes, and even comprehensive bans and restrictions on foreign investments, especially if these foreign investments involve dual-use technological advancements for both civilian and military applications. With this economic policy leverage, these governments further pledge massive support for clean and green technology in the current global fight against climate change. Additional examples of economic policy leverage include the Inflation Reduction Act and the CHIPS and Science Act. In our view, however, this new homeland industrial policy stance may struggle to make global supply chains more resilient. The resultant economic policy levers may not suffice to reduce wealth and income disparities in support of greater economic growth, price stability, and maximum employment. The elusive quest of new homeland growth miracles may ultimately transform into a bad beauty contest for both winners and losers. In due course, these winners may turn out to be those chosen national champions in some strategic sectors.

In search of more robust and more resilient global supply chains, governments and companies both seek to protect themselves from major disruptions, whether these disruptions result from the deliberate weaponization by dictators (such as Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping) or the boom-bust vicissitudes of free markets. In practice, the fundamental support for more robust global supply chains may lead to dramatically higher costs than benefits. In many of the western countries, some politicians now attempt to decouple the world economy from Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. Others speak of strategically de-risking at least one-third of total trade from these authoritarian regimes. In the post-pandemic years, China-plus-one has become a new boardroom mantra. This mantra states that each business should supplement a Chinese supplier with a low-cost backup outside Mainland China. In some cases, reshoring global supply chains near U.S. friends and western allies can help attain these business goals.

Many multinational companies regard more robust and more resilient global supply chains as a vital lesson from the Covid pandemic crisis of 2020-2022. During these years, many goods and resources were in short supply. Specifically, these goods and resources included medical supplies such as masks, vaccines, and ventilators, semiconductor microchips, oil, coal, and natural gas. As a result, these shortages led to substantial price hikes up to 9.7% per annum in many parts of the world. In response to these price hikes, central banks raised interest rates to tame inflation. Some trade companies had a hard time reshoring their regional supply chains with raw resources. As global supply chains have become leaner and more efficient in the past few decades, they have also become extremely vulnerable to disruptions in the face of global shocks. From the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 to the more recent Covid pandemic crisis of 2020-2022, these global shocks cause near-term shortages, bottlenecks, and price hikes across multiple sectors at once.

Many technologists fear that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) may weaponize its massive supply chains to achieve political goals. Specifically, China may invade Taiwan as part of the CCP propaganda to reunify the island with the Greater China region. This invasion would force a complete shutdown of Taiwan’s semiconductor foundries. As Taiwan now produces about 65%-70% of the world’s semiconductor microchips, the prices would rocket everywhere for many high-tech products such as smartphones, computers, cloud servers, and data centers around the world.

Some business observers and media commentators consider vertical integration along the global supply chains. In many cases, vertical integration involves buying up upstream suppliers to ensure steady flows of intermediate goods and resources. In recent years, the American EV maker, Tesla, broke ground on a lithium refinery plant in the Corpus Christi area of Texas. As a fraction of total gross output, vertical integration continues to rise in a cost-effective manner. This business strategy has proven to be both sound and efficient in helping rebuild more resilient global supply chains.

Many multinational corporations seek new upstream suppliers and trade partners outside China. From 2018 to 2024, strategic imports from China to the U.S. and its western allies fell from more than 35% to only 25%. These imports included optical products, computer parts, and raw resources for some military weapons, missiles, and navigational systems. Today, Chinese imports are worth no more than 7% of the cost of goods sold in the S&P 500 stock market index. Some high-tech analysts believe that Apple may choose to shift 25%-35% of iPhone manufacturing capacity from China to India, Vietnam, and Indonesia in the next decade. This diversification helps derisk from China in support of more resilient global supply chains.

These macro trends can continue as many western companies shift their operating focus away from China. In fact, global greenfield foreign direct investment (FDI) to China has declined dramatically from almost 9%-15% in 2000 to no more than 3% in mid-2024. Some western countries, specifically, France and Germany, attempt to pull FDI money out of China on a net basis. In recent years, the U.S. and western allies continue to strictly enforce outbound-investment screening requirements to stop specific technological transfers to China in some strategic sectors.

It can be an enormous task for both governments and companies to decouple-and-derisk from China. Following France and Germany, Australia now seeks to divest enthusiastically from China. However, the recent data show that it takes more than 35 years for both the Australian government and companies to pull out only half of the total FDI that the Aussies maintain in China. After all, it can take a long time to wean Western consumers off Chinese-made products and supplies.

In addition to the recent deglobalization of FDI flows away from China, another real problem is that many alternatives to China are not palpable. Although Vietnam and Thailand now collectively receive more greenfield FDI than China does each year, these alternatives to China have yet to establish democratic regimes in support of free-market capitalism. India is another alternative beneficiary of greater greenfield FDI flows, and India adopts the western democratic system in favor of free markets, foreign investments, and liberal ideas. Yet, economic inequality and poverty persist in India. These social disparities often deter and dissuade longer-term investments by western governments and multinational corporations. Likewise, Indonesia is not free from the same long prevalent socio-economic issues. Although Indonesia has enjoyed its democratic dividends since the fall of the Suharto authoritarian regime in 1998, democratic consolidation remains a work-in-progress in Indonesia today. Overall, these alternatives to China may not be palpable for western governments and companies to consider rebuilding new global supply chains there.

Although Chinese imports have declined dramatically in many markets worldwide, western countries continue to import a lot more from East Asian countries that rely ever more heavily on Chinese exports. Today, the U.S. spends more than 3 times as much on imports from the Vietnamese computer industry as the U.S. did in 2011. Over the same period, Chinese imports to Vietnam of machinery for PC production rose by 75%. Perhaps this long prevalent reliance on Chinese exports reveals the weakest link of the current global supply chains.

To make the current global supply chains more resilient, we would need to be able to re-shore alternative production capacity immediately to meet macro changes in global demand. We would further need to ensure that geopolitical rivals would not cause major disruptions at any point. In the hot pursuit of a supply-chain revolution, the world remains highly interdependent. Many governments and companies now pay much more attention to the progressively higher cost of keeping core business operations worldwide. In this broader context, the new homeland industrial policy may turn out to be an elusive quest of growth miracles at some historical junctures. No one can replicate these past successes and growth miracles elsewhere.

From North America to Europe, Japan, and South Korea, many governments offer generous state subsidies, tax credits, and other non-cash incentives to support the homeland production of semiconductor microchips, lithium batteries, solar panels, rare earths, and many other strategic commodities. These strategic commodities include nickel, aluminum, iron, uranium, palladium, titanium, oil, coal, and natural gas. In combination, these strategic resources support manufacturing capacity for airplanes, missiles, cruise ships, navigational systems, electric vehicles, flat-panel televisions, computers, smartphones, electronic appliances, and hydrocarbon and nuclear power plants. Overall, these ambitious state support plans and programs may soon collide with reality. It is hard for governments to create strategic sectors with long-term viable streams of sales and profits. The economic costs of industrial policy tend to be prohibitively high.

On the whole, industrial policy success are few and far-flung worldwide. In modern human history, many governments turn to the growth miracles of some East Asian tiger economies such as South Korea and Taiwan. In the 1970s, for instance, the South Korean government carved out the seminal industrial push in support of the Heavy Chemical Industry (HCI). During those years, the South Korean government provided hefty generous state subsidies, tax breaks, and research grants to boost HCI homeland production. As a result, all these state support programs eventually led to substantial HCI exports worldwide. From the 1980s to the 1990s, the South Korean government further played a vital role in rebuilding the homeland car sector. The net beneficiaries were the world-class carmakers Kia and Hyundai. Likewise, the Taiwanese government provided astronomical state subsidies, tax credits, and R&D guidance and collaboration in support of the homeland semiconductor sector from the mid-1980s to present. The net beneficiaries were Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC), MediaTek, Foxconn, Pegatron, ASE Group, AU Optronics, LITE-ON, UMC, and Siliconware Precision among many others. Indeed, both TSMC and Foxconn decided to diversify their global supply chains to America, France, Germany, and Japan in response to the broad demands and requirements by western governments. Government support and intervention seemed to play an important role, at least in the early stages of strategic sector development, for both South Korea and Taiwan.

However, government support and direction that can combine to help rebuild some strategic sectors with competitive advantages usually turn out to be ineffective and unsuccessful. State subsidies, tax breaks, and research grants tend to reward the winners to the detriment of the losers in the broader context of homeland industrial policy. Over many decades, the winners often turn out to be those chosen national champions in some strategic sectors. Even though these strategic assets result in better economic growth and full employment around the regional high-tech clusters and theme parks, the homeland industrial policy may inexorably exacerbate social disparities in both wealth and income. Today, economic inequality is a widespread and pervasive problem in both South Korea and Taiwan, although some may argue that economic inequality has become a global phenomenon in recent years.

At the margin, helping one company with state subsidies and tax breaks may harm others. In the grand scheme of Made in China 2025, the CCP government provided substantial financial support to both tech titans and lean startups in some strategic sectors such as electric vehicles, renewable energy power plants, semiconductor microchips, 5G high-speed broadband telecom networks, and artificial intelligence applications in defense, health care, education, trade, finance, and technology etc. Yet, there is little statistical evidence of efficiency gains, productivity improvements, or increases in R&D expenditures, patents, and profits in those tech titans and lean startups. In China, these high-tech national champions now include Alibaba, Baidu, Tencent, BYD (the biggest EV maker in China and therefore a global rival to Tesla), ByteDance (the parent company of the video-sharing app TikTok), Xiaomi (a cost-conscious producer of smartphones, wearable devices, and electronic appliances in China), Huawei (a tech titan in semiconductor microchip design and high-speed broadband telecommunication), Lenovo (a global PC manufacturer in China), JD (an e-commerce hub in Mainland China), DJI (the world’s largest drone producer), Pinduoduo (a mainstream Chinese online retailer), and Meituan (a Chinese online shopping platform for consumer products and services such as travel, food delivery, and entertainment). Despite their wondrous successes, sales, and profits in recent years, these tech titans struggle to spread stellar fortunes outside the major cities along the east coast of Mainland China. Indeed, the total factor productivity across China has probably fallen since the new turn of the millennium.

In India, the government provides cash and non-cash incentives for each additional unit of production of high-tech consumer products such as smartphones and PCs. To the extent that India’s exports of these high-tech products soar, this government intervention seems to be a viable homeland industrial policy. However, these new fortunes may not trickle down the 4 major caste clusters of the social hierarchy in India. At this early stage of strategic sector development, there are no clear victors in India. After all, the new industrial policy successes and fortunes fail to eradicate corruption in India. Substantial social disparities in wealth, income, and health care quality still seem to persist in India.

As in the 1990s, government attempts to boost their home production of microchips now run into trouble. Dr. Morris Chang, the founder of TSMC, told the former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi that U.S. efforts to rebuild microchip manufacturing capacity at home would likely fail in due course. TSMC expects to delay the core operations of its first plant in Arizona until 2025 due to a statewide shortage of semiconductor specialists there. In this case, the U.S. homeland industrial policy stance seems to defy the basic economic law of comparative advantage across countries and even continents.

Economic costs emerge from another direction. As a result of deliberate retaliation, some of the most aggressive measures come from China. In recent times, the CCP government imposed export controls on gallium and germanium, 2 raw resources in support of some high-end military technology. Also, the CCP government placed 2 major American arms-makers, Lockheed Martin and Raytheon, on its blacklist of unreliable entities after these U.S. companies shipped military weapons to Taiwan, the latter of which China regards as part of its territory. In effect, China blocked the 2 U.S. entities from engaging in new investments and even trade activities in China, among some other restrictions.

Today there is no or little sign of a ubiquitous innovation boom worldwide. Although there are some steady international investments in intellectual-property products with patents and trademarks, the current dollar amounts of both R&D investments and expenditures are well below the pre-pandemic macro trends. Also, the current global productivity growth has been below the pre-pandemic norm in recent years. In the hot pursuit of high-quality economic growth, many governments should focus on not only the pace of growth, but also more importantly, the distribution of growth. In most cases, a more equal and more equitable society helps promote high-quality economic growth and employment with both price stability and robust asset market valuation. If governments can manage to substantially reduce social disparities in average income to boost the fortunes of both blue-collar and white-collar workers, perhaps it matters much less when real GDP per capita increases at a slower pace. Nevertheless, some free-market advocates and proponents still seem to overstate the progressive potential of homeland industrial policy.

In recent decades, many old-style jobs have disappeared in large numbers across different parts of North America and Europe. Also, health care and life expectancy improvements have continued to slow in many metropolitan regions of the rich and middle-income countries. Many economists blame these 2 major macro trends on an almighty surge in trade, especially trade with China. In the 25 years from 1999 to 2024, exports from China to the rich world rose at a 17% average annual pace. Rapid increases in imports from China cause higher unemployment and blue-collar job displacement, reduce labor-force participation, and further lower wages in local labor markets from North America to Europe. In some specific sectors with greater trade and import competition from China, western workers spend more time out of work than their peers in many other sectors.

Some other economists disagree. The long-term decline in western manufacturing employment arises largely from technological improvements, not necessarily trade and import competition from China. Because AI robots, machines, and computers usually help humans accomplish more today, these technological advancements help enhance total factor productivity gains with fewer workers. In the broader club of high-income and middle-income countries, manufacturing jobs remain 2 million below their pre-pandemic peak. In Brazil, Chile, China, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Turkey, the governments there pursue state manufacturing development with enthusiasm. However, these state schemes have so far created no more than 20% of additional manufacturing jobs that the governments envisioned to attract almost a decade ago. After all, technological advancements can dovetail with trade import competition from China to depict a more complete picture of the current homeland industrial policy stance.

In some high-income economies such as Canada, France, Australia, New Zealand, and Singapore, the new jobs cater to high-skill knowledge workers. These workers design, develop, and then monitor AI robots, machines, and computers to service both domestic and overseas client requests. In these special cases, the high-skill knowledge workers are not members of the left-behind working class. Almost 85% of these high-skill knowledge workers retain tertiary education and even graduate qualifications. In the absence of higher education, any state-led expansion of the manufacturing sector would likely cause adverse ripple effects on both blue-collar and white-collar job creation, maximum employment, and economic growth.

In addition to the productivity gains for high-skill knowledge workers in the rich and middle-income countries, many others win in the third world too. During the golden age of free market capitalism and globalization from 1989 to 2004, global poverty and inequality fell sharply. Opening the Cold War borders with dramatically lower tariffs empowered all new WTO members to enjoy the sales, profits, and rewards of free trade. Western companies opened their world factories and plants for mass production in China, India, Indonesia, Brazil, Chile, Malaysia, Turkey, South Africa, and so forth during all these years. Although these western companies came under criticism, these offshore manufacturing jobs paid above-average wages with better workplace safety conditions. A rising tide lifts all boats.

Today, some aspects of the current homeland industrial policy stance can help the global poor. At a recent summit in Hiroshima, Japan, the G7 leaders affirmed their longer-run commitment to the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment, a $600 billion investment splurge worldwide. In effect, this G7 investment program now serves as a counterweight to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, an infrastructure program trying to pull poor countries into China’s economic orbit. Other economists point out that the recent rush to secure global supply chains with clean energy can perhaps increase the broader demand for strategic commodities. In turn, exporters can benefit from these macro trends in the right direction. Indeed, exports from the third world are now at least 35% to 55% higher than their pre-pandemic level. This impressive growth has been faster than the global average.

Since China became part of the WTO in 2001, the country’s integration into global markets has dramatically helped the middle kingdom pull 800 million people out of extreme poverty. Today, however, western leaders try to hobble China’s economic growth and technological progress and dominance in some strategic sectors (such as AI, 5G, cyber security, ground defense, naval support, cruise missile navigation, virtual reality, high-speed broadband telecommunication, semiconductor microchip design and mass production, and central bank digital currency (CBDC) etc). It may not be hard for us to imagine a new alternative macro trend where poverty in China progressively stops its recent decline, turns the tide, and then even rises as a result. In the corridors of power from Brussels to Washington, most western leaders would not pay much attention to this alternative macro trend in China. In response to hefty tariffs, embargoes, investment restrictions, and several other trade bans, barriers, and frictions from the U.S. and its western allies, China would probably resort to a major baseline backlash through the WTO and UN Security Council in due course. In this fresh zero-sum game of fair trade, the far-flung fear of retaliation helps deter any further strike in the first place.

In support of more resilient global supply chains, recent attempts by rich countries to produce more at home may deprive China and other East Asian tiger economies of lucrative employers. These recent attempts continue to reduce the vital transfer of efficient business management practices and technological advancements from the rich world to the poor. Since the third wave of democratization worldwide from the mid-1980s to 2000, this vital transfer has been one of the major sources of new income growth for Mainland China, Hong Kong, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam. In light of geopolitical tensions, these middle-income economies cannot resist the temptation to choose between further securing global supply chains for China and for America. In these East Asian tiger economies, the governments lack the fiscal firepower to provide state subsidies and tax credits on the massive scale of North America and Europe. For this reason, these economies may lose out on attracting fair trade and foreign direct investment (FDI). Some low-income countries and regions face the same fiscal problem. A recent World Bank study shows that a total shift toward reshoring global supply chains may cause 52 million people into extreme poverty by 2035. This poor population spans East Asia, Middle East, Eastern Europe, and Africa. In summary, the new homeland industrial policy stance may not help reduce social disparities in wealth and income in many rich, middle-income, and low-income countries and regions.

From carbon taxation to hydropower storage, the old proposals for climate change risk management have proven insufficient. Average global temperatures are hence on track to rise by more than 2 degrees Celsius well above the pre-industrial levels. The new homeland industrial policy stance spans not only reshoring more resilient global supply chains, but also further accelerating the green transition toward net-zero global carbon emissions.

Since France and Germany brought in generous state subsidies for solar power in the mid-2000s, the global price of solar power generation has significantly tumbled as a result of both scale and scope economies and the current Chinese homeland industrial policy. Over the past decade, the amount of solar power generation has dramatically doubled in France and Germany each year. In America, the Inflation Reduction Act provides $400 billion to $1 trillion over the current decade to support solar power, hydrogen power production equipment, high-capacity lithium batteries, and many other types of renewable energy. Japan seeks to put $150 billion worth of both state subsidies and tax breaks toward its own Green Transformation policy. A recent survey by the International Energy Agency shows that many governments have dramatically committed well more than $2 trillion worth of state subsidies, tax credits, and other fiscal incentives to clean and green energy. With this worldwide green energy transformation, many governments aim to substantially reduce both the costs and prices of world energy. With better environmental protection, the new green energy transformation thus accords with the broader macro mandate of price stability, full employment, and robust and steady economic growth. This approach further accords with the lofty pursuit of high-quality economic growth as the current net-zero transformation helps reduce the hefty economic costs of extreme weather events, the latter of which have become more severe and less rare in recent years. In the positive light, the current homeland industrial policy stance may help achieve the first-best optimal outcomes in climate change risk management worldwide.

In support of this long prevalent net-zero transformation worldwide, state subsidies, tax breaks, and some other cash and non-cash incentives comprise large numbers of domestic content requirements as part of the current homeland industrial policy. For each American buyer to receive the complete $7,500 tax rebate for his or her electric vehicle (EV) under the Inflation Reduction Act, the vast majority of EV parts and components need to have been made in North America. Canada provides key financial support for EV makers that have chosen to set shop there. Many countries in Latin America spend much in a joint effort to start their own local green hydrogen power generation industry. In Britain, the opposition leader Keir Starmer promises that the Labor Party’s green energy transformation policies would create 200,000 jobs for Brits. This bold approach is part of an attempt to marry climate change risk management with social policy.

Any plan to free a modern economy from fossil-fuel dependence can create losers. To succeed politically, this plan must mobilize more powerful winners than losers. Millions more people who work on net-zero green energy can mean millions more people with sound and sufficient incentives to resist attempts by fossil-fuel interests to roll back the clock.

However, green state subsidies, tax rebates, and many other incentives may come with huge risks. At the outset, a business problem arises when foreign companies cannot sell raw resources, intermediate goods, and many other supplies to the U.S. domestic market. As foreign companies lose U.S. customers specifically or access to the U.S. market more broadly, these companies may lose both scale and scope economies altogether. In addition to the key loss of access to the American market, there is little room for trade diversion of the same raw resources and intermediate goods to many other foreign companies and markets. A recent survey shows that even though green energy providers benefit substantially from the new homeland industrial policy stance, most other producers and manufacturers lose out so much that the new Inflation Reduction Act may inadvertently slow the green transition on a global scale. When we mull over this net result in addition to green subsidies and domestic-content requirements outside the U.S. and Canada, the global drag may be even bigger. In the worst-case scenario, the current homeland industrial policy stance may help achieve only the second-best, or suboptimal, outcomes in climate change risk management.

Time is another concern. The world needs to decarbonize fast. Yet, it takes many years for countries to build up domestic capacity in green energy and transport. In more pragmatic terms, no one can build a battery factory overnight. U.S. governors and senators seem to indicate that they prefer building as much homeland capacity as possible over decarbonization as quickly as possible. If the homeland industrial policy stance insulates domestic companies from worldwide competition, they may try less hard to discover the latest disruptive innovations in green energy, transport, and solar, nuclear, and hydrogen power generation.

Do the pros of green subsidies outweigh the cons in the long run? It is hard to say at this stage of the global green transformation toward net-zero carbon emissions. Perhaps powerful green interest groups can beat fossil-fuel lobbyists at their own game. When many governments offer generous state subsidies and tax credits on green energy and transport, these fiscal programs may turn out to be inefficient to the extent that the cons ultimately outweigh the pros of green subsidies in due time. In that worst-case scenario, the current homeland industrial policy may or may not help achieve the first-best or optimal outcomes in climate change risk management. The new homeland industrial policy stance spans not only reshoring more resilient global supply chains, but also further accelerating the green transition toward net-zero global carbon emissions. In the meantime, the western governments seem to be trying to kill 2 birds with one stone, especially when the birds are moving targets that fly in different directions. In the best likelihood of success, these governments may eventually miss both birds when push comes to shove.

The new homeland industrial policy stance now tends to tilt toward reshoring more resilient global supply chains for critical technological advancements such as 5G high-speed broadband telecom networks, semiconductor microchips, and artificial intelligence (AI) applications in defense, health care, education, trade, finance, and cyber security. In support of less wealth and income inequality, these macro trends help promote greater high-quality economic growth, full employment, price stability, and robust macro-financial asset market valuation. In the meantime, many western governments face relatively bleak prospects for global peace, economic prosperity, and political stability.

A profound shift in the homeland industrial policy stance is now under way. Across the rich world, many governments offer generous state subsidies, tax rebates, and other cash and non-cash incentives to build some strategic sectors in green energy, electric transport, generative AI, high-speed mobile cloud telecommunication, and semiconductor microchip design and production. This current homeland industrial policy stance is probably the biggest policy shift worldwide in our lifetime.

In the rich and middle-income countries, many governments believe that this new homeland industrial policy stance holds great promise. When global supply chains become more resilient in the absence of extreme disruptions, supply-side inflation would be reasonably low and steady. The global society would become more equal. Workers would have clear economic incentives to favor green energy in support of climate change risk management goals. The current homeland economic science might even shift the world out of its recent productivity slump.

Globalization failed to produce the global peace, economic prosperity, and political harmony that its fervent proponents had expected in the 1990s. Despite its recent vital participation in world affairs through the WTO, WHO, and UN Security Council, China seems ever further from becoming a new democratic regime. China still has subpar human-rights records in Tibet and Xinjiang, and China continues to menace Taiwan through both diplomatic and military means. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine reveals geopolitical tensions and vulnerabilities in Easter Europe. Also, the current conflict between Israel and Iran, Hamas, and the Palestinians further deepens long prevalent geopolitical cleavages in the Middle East. In recent years, this furtive de-globalization redivides the world into the U.S. and its western allies vis-à-vis Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. The history of great-power competition seems clear. Rising powers often choose to assert themselves through many military, diplomatic, economic, geopolitical, and technological ways and manners that incumbents tend to avoid by all means. This time may not be different, especially when history often repeats itself.

Overall, globalization had helped reduce extreme poverty for the poor in many low-income countries. Opening postwar global markets caused the fastest decrease in world poverty ever. Trade agreements often specified higher standards, conditions, and requirements in support of both workplace safety and environmental protection in poor countries. Under the current neoliberal world order, the average rate of fatal occupational injuries outside the rich world fell from well over 10 per 100,000 in the year 2000 to slightly above 3. Today, food is cheaper, and clothes are cheaper too. Through free trade networks and low tariffs worldwide, globalization reduces prices everywhere, boosts income per capita, and stops wars in some cases.

However, globalization did fail some people, especially blue-collar workers in the left-behind rural areas and regions of North America, Australia, Britain, and Europe. Wealth and income disparities have grown substantially by historical standards in these rich economies. Also, production growth has become weak and sluggish in the rich world. These fault lines exacerbate social issues from rural unemployment to a widespread lack of economic equality in health care, education, social security, trade, finance, and technology. In summary, the current homeland industrial policy seems to integrate domestic economic opportunities with foreign affairs. In addition to perverse incentives, carrots, and sticks, political misconceptions may lead states, cities, and companies to miss the multiple divergent policy goals.

In the current geopolitical world, it is quite reasonable for leaders, lawmakers, and many other politicians to focus on national security concerns. In practice, the vast majority of bilateral trade and investment relations between China and the U.S. are best left to private decisions. Yet, it would make much sense for the U.S. to restrict the bilateral trade and investment relations in some sensitive and strategic sectors, such as defense, finance, infrastructure, and technology. These restrictions would reduce the potential damage that China might do if the Chinese government turned hostile to the U.S. and its own western allies and trade partners. In pragmatic terms, American trade and investment restrictions should focus on some potential transfer of sensitive and strategic technological advancements in support of better national security and global peace and prosperity.

This legitimate policy goal should lead to narrow target investment restrictions on what genuinely constitutes dual-use technological advancements for both civilian and military applications. In practice, this approach produces a free-for-all version of both homeland industrial policy and trade protectionism. As a consequence, the critical global supply chains may become less resilient in response to some political concerns and considerations. The world may experience subpar economic growth in terms of total GDP, total factor productivity, and technical progress. To the extent that poor countries cannot match the fiscal firepower of rich countries, the current homeland industrial policy tilts in favor of the U.S. and western allies. This gradual development tends to recur at the expense of both middle-income and low-income countries. Away from global supply chains and free trade networks, these countries may grow more slowly. As a result, extreme poverty and economic inequality tend to persist in these countries over a longer time window. As the U.S. and its western allies attempt to decouple-and-derisk from China, the world economy needs to deal with the potential backlash from China and its nearest trade partners Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

The costs of the shift continue to compound significantly in due course. As the U.S. and western allies start to lose credibility in their joint cause of fair trade, the current shift seems to further erode the postwar multi-lateral free trade system worldwide. Indeed, the western governments encourage more trade protectionism with higher tariffs, quotas, embargoes, foreign investment restrictions, and other trade barriers. The adverse fiscal ripple effects of lower productivity gains further weaken global supply chains with pervasive price increases. In recent years, many central banks apply substantial interest rate hikes to tame inflation around the world.

It there is a bright spot here, it is only insofar as every cloud has a silver lining. The current homeland industrial policy results in generous state subsidies, tax breaks, and other cash incentives in support of the global green energy transformation. In practice, this positive macro trend helps speed up the next transition toward green energy and transport worldwide. In the less carbon-intensive world economy, every global citizen can enjoy cleaner and greener air, water, and food in a cost-effective manner. Better climate change risk management can help enhance environmental protection with significantly lower economic costs of rare extreme weather hazards. The open controversy is whether these real benefits translate into both robust and steady economic growth, employment, price stability, and asset market valuation worldwide in the longer run.

As of mid-2025, we provide our proprietary dynamic conditional alphas for the U.S. top tech titans Meta, Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon (MAMGA). Our unique proprietary alpha stock signals enable both institutional investors and retail traders to better balance their key stock portfolios. This delicate balance helps gauge each alpha, or the supernormal excess stock return to the smart beta stock investment portfolio strategy. This proprietary strategy minimizes beta exposure to size, value, momentum, asset growth, cash operating profitability, and the market risk premium. Our unique proprietary algorithmic system for asset return prediction relies on U.S. trademark and patent protection and enforcement.

Our unique algorithmic system for asset return prediction includes 6 fundamental factors such as size, value, momentum, asset growth, profitability, and market risk exposure.

Our proprietary alpha stock investment model outperforms the major stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq. We implement our proprietary alpha investment model for U.S. stock signals. A comprehensive model description is available on our AYA fintech network platform. Our U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) patent publication is available on the World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) official website.

Our core proprietary algorithmic alpha stock investment model estimates long-term abnormal returns for U.S. individual stocks and then ranks these individual stocks in accordance with their dynamic conditional alphas. Most virtual members follow these dynamic conditional alphas or proprietary stock signals to trade U.S. stocks on our AYA fintech network platform. For the recent period from February 2017 to February 2022, our algorithmic alpha stock investment model outperforms the vast majority of global stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI USA, MSCI Europe, MSCI World, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq etc.

With U.S. fintech patent approval, accreditation, and protection for 20 years, our AYA fintech network platform provides proprietary alpha stock signals and personal finance tools for stock market investors worldwide.

We build, design, and delve into our new and non-obvious proprietary algorithmic system for smart asset return prediction and fintech network platform automation. Unlike our fintech rivals and competitors who chose to keep their proprietary algorithms in a black box, we open the black box by providing the free and complete disclosure of our U.S. fintech patent publication. In this rare unique fashion, we help stock market investors ferret out informative alpha stock signals in order to enrich their own stock market investment portfolios. With no need to crunch data over an extensive period of time, our freemium members pick and choose their own alpha stock signals for profitable investment opportunities in the U.S. stock market.

Smart investors can consult our proprietary alpha stock signals to ferret out rare opportunities for transient stock market undervaluation. Our analytic reports help many stock market investors better understand global macro trends in trade, finance, technology, and so forth. Most investors can combine our proprietary alpha stock signals with broader and deeper macro financial knowledge to win in the stock market.

Through our proprietary alpha stock signals and personal finance tools, we can help stock market investors achieve their near-term and longer-term financial goals. High-quality stock market investment decisions can help investors attain the near-term goals of buying a smartphone, a car, a house, good health care, and many more. Also, these high-quality stock market investment decisions can further help investors attain the longer-term goals of saving for travel, passive income, retirement, self-employment, and college education for children. Our AYA fintech network platform empowers stock market investors through better social integration, education, and technology.

Andy Yeh (online brief biography)

Co-Chair

AYA fintech network platform

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone’s first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2018-06-06 09:39:00 Wednesday ET

Donald Trump and Kim Jong Un meet, talk, and shake hands in the historic peace summit between America and North Korea in Singapore. At the start of the bila

2017-08-31 09:36:00 Thursday ET

The Trump administration has initiated a new investigation into China's abuse of American intellectual property under Section 301 of the Trade Act of 19

2023-12-08 08:28:00 Friday ET

Tax policy pluralism for addressing special interests Economists often praise as pluralism the interplay of special interest groups in public policy. In

2025-06-05 00:00:00 Thursday ET

Former New York Times team journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Charles Duhigg describes, discusses, and delves into how we can change our respective lives

2019-12-13 09:32:00 Friday ET

Saudi Aramco aims to initiate its fresh IPO in December 2019. Several investment banks indicate to the Saudi government that most investors may value the mi

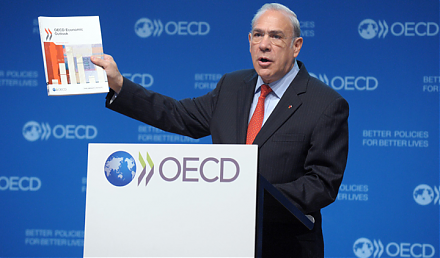

2019-03-27 11:28:00 Wednesday ET

OECD cuts the global economic growth forecast from 3.5% to 3.3% for the current fiscal year 2019-2020. The global economy suffers from economic protraction