2025-07-01 13:35:00 Tue ET

treasury deficit debt employment inflation interest rate macrofinance fiscal stimulus economic growth fiscal budget public finance treasury bond treasury yield sovereign debt sovereign wealth fund tax cuts government expenditures

We delve into the mainstream public policy implications of financial deglobalization in recent years. The U.S. and its western allies impose some economic sanctions on global trade and finance in relation to China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. In addition to these sanctions, hefty tariffs, embargoes, and foreign investment bans and restrictions further limit the macrofinancial clout of these countries. As the U.S. and its western allies cut off favorable trade relations with China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea, the current Russia-Ukraine war, the potential invasion of Taiwan by China, the relentless conflict between Israel and Hamas and the Palestinians, and several other geopolitical tensions exacerbate recent asset market fragmentation in the broader context of financial deglobalization. Even though the American dollar remains the dominant global reserve currency and global supply chains prove to be more resilient, global capital flows start to fragment in different directions in the particular context of financial deglobalization. The postwar world order of free trade continues to fall apart at a relatively slow and gradual pace.

The postwar global institutions that safeguard the old world order of free trade are either already defunct or deficient with a lack of longer-term credible commitments these days. The World Trade Organization (WTO) turns 30 in 2025, but continues to have spent more than 5 years in stasis due to western neglect. The World Bank seems to be caught between fighting world poverty and enriching the upper social echelon in new market economies with higher population dividends such as China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) confronts its identity crisis and remains stuck in the middle between global financial stability and green finance in support of better climate risk management worldwide. The World Health Organization (WHO) now needs to cope with the post-pandemic public health risks and threats worldwide, such as new variants of the corona virus. In recent years, the U.N. security council fails to secure world peace and prosperity due to the Russia-Ukraine war in Eastern Europe, the relentless conflict between Israel and Iran, Hamas, and the Palestinians, as well as the recurrent flash points in the North Korean peninsula, Taiwan, South China Sea, and wider Pacific Ocean. The International Court of Justice attempts to weaponize the U.S. and its western allies by issuing arrest warrants for President Vladimir Putin and others who launch wars against humanity, but the Court has little jurisdiction over Russia and Ukraine in Eastern Europe, the Gaza Strip in Middle East, and the Pacific first island chain from the North Korean peninsula and Japan to Taiwan and the Philippines.

The resultant fragmentation of free markets in new democracies imposes a stealth tax on the global economy, in the form of higher inflation or lower purchasing power for each marginal dollar. Unfortunately, human history shows that deeper financial deglobalization may inadvertently worsen the current tilt toward secular stagnation worldwide. Today, a similar rupture seems all too imaginable. The return of Donald Trump to the White House, with his zero-sum worldview, would probably continue the gradual and recurrent erosion of global institutions, norms, and principles all in support of both free trade and democratic capitalism. The far-flung fear of a second wave of low-cost imports from China would likely accelerate this global trend. Any outright war between America and China over Taiwan, or between the NATO and Russia, would further cause an almighty collapse of the world trade system.

Nowadays, it is fashionable for economists to criticize free-market globalization as the root cause of social disparities in wealth and income worldwide, global financial imbalances, as well as climate change risks (even the increasingly hefty economic costs of rare extreme weather events). However, the free trade achievements from the 1990s to the early-2000s help mark the high point of liberal capitalism and then continue to be a rare, unique, and inimitable episode of human history. Through a free ride on the transition to new market economies, China, Brazil, India, Indonesia, and the Philippines integrated into the world economy. As a result, many hundreds of millions escaped poverty. Also, the current infant mortality rate worldwide is less than half what the rate was back in the 1990s, due to greater clean water and food. The proportion of global deaths due to inter-state wars and conflicts has hit a post-war low, less than a thousandth of 0.2% today, down from almost 40 times as high more than 50 years ago. Today, many leaders and politicians hope to replace the old Washington consensus on free trade and market capitalism. The Washington consensus depicts a world economy where poor countries enjoy capital spending booms to catch up on economic growth and employment with rich countries. Due to economic and non-economic risks and issues such as climate change, extreme weather, pandemic disease control, credit contagion, and nuclear proliferation etc, many leaders and politicians attempt to close the economic gap between rich and poor countries through alternative means of trade, finance, and technology.

Indeed, the postwar world order of free trade achieved a merry marriage between the U.S. peace principles and strategic interests. At the same time, this new liberal world order further brought real economic benefits to the rest of the world. In some parts of the world, however, poor residents continue to suffer from the World Bank and IMF’s inability to resolve the sovereign debt crisis after the Covid-19 pandemic years. Several middle-income countries such as India and Indonesia hope to trade their way to riches, but these countries end up trying to exploit free-trade loopholes and opportunities due to financial deglobalization and asset market fragmentation. In practice, the global economy should remain robust, resilient, and predictable in integrating most prior trade blocs and regions into the new world order of fair trade. In due course, the fair-trade integration helps ensure global peace and prosperity with the long prevalent American-driven institutions, norms, and principles in favor of free-market capitalism, democratization, and the lofty pursuit of a good life.

From the mid-1990s to the early-2000s, the global financial order resembled a hub-and-spoke system. America dominated at the center of this global financial system. The recent Russian invasion of Ukraine prompted severe economic sanctions from the U.S. and its western allies to quash global links in trade and finance with Russia. The largest banks across Russia, Sberbank, VTB, Gazprombank, Promsvyazbank, and Russian Agricultural Bank, became the main targets of western sanctions after Putin launched the Russian war against Ukraine. To Muscovite bankers, financial deglobalization is alive and well. For trade and finance, the global system no longer involves Russian banks, insurers, and other non-bank financial institutions. These Russian bank examples reflect an epochal fundamental shift in the global financial system. From China and Russia to Iran and North Korea, many forces combine to reduce each dictatorial regime’s dependence on western capital flows, institutions, payment networks, and specifically, the American dollar. As a result, this financial deglobalization breaks the world into several unique trade blocs, zones, and asset market fragments.

In view of dramatic changes to the global economic geography over the past few decades, this financial deglobalization seems inevitable. In due time, asset market fragmentation arises on the current horizon. Indeed, the rapid rise of China causes its fair share of global economic output to balloon significantly in recent years, and many other countries have grown alongside China. Today, the 10 largest middle-income economies account for more than one third of global economic output. Due to this financial deglobalization, the mainstream financial centers of East Asia have spread from Hong Kong, Singapore, and Tokyo to Beijing, Shanghai, Dubai, Taipei, and Kuala Lumpur. This proliferation helps spread out massive wealth and income through new financial centers around the world. At the same time, this proliferation may inadvertently lead to larger social disparities in wealth and income, especially in rich and middle-income countries. A rising tide lifts all boats. As a result, greater economic inequality reflects the long prevalent fragmentation of financial markets. Financial deglobalization often tends to persist at the expense of poor members of human society. From better climate change risk management to renewable energy and extreme-weather disaster recovery, many governments seek to further reduce social disparities in wealth and income through greater state subsidies, tax rebates, and other economic incentives in support of net-zero carbon emissions worldwide. These state programs help better serve the new homeland industrial policy stance in favor of national champions in several strategic sectors such as semiconductor microchip design and production, 5G high-speed cloud telecommunication, virtual reality, artificial intelligence, green energy and transportation, and the metaverse. Despite financial deglobalization and asset market fragmentation, these economic programs help prepare global citizens for a better and brighter future in the grand pursuit of a good modern life.

In the old hub-and-spoke era of global finance, the U.S. monetary policy with mild interest rate adjustments, flighty institutional investors, and bank loan imbalances combined to export crises around the world (with some help from Europe). By stark contrast, the more distributive global financial system now looks like a firm fortress of asset market stability. Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, many new economies have become more robust and more resilient to any recurrent volatility. In the absence of market implosions in recent years, the Federal Reserve System has raised interest rates more rapidly than any episode since the 1980s. Many low-income and middle-income countries begin to build vital financial infrastructure of their own, as new national payment systems, wire wallets, and central bank digital currencies (CBDC) come online. In response to these competitive pressures and threats, incumbents strive to upgrade their own clunky digital architecture in a cost-effective manner.

Geopolitical tensions, or full-blown wars, may tug the global financial system apart altogether. In light of recent financial deglobalization, many countries and investors choose some particular trade blocs and never venture outside. The resultant global financial system would be subject to more volatile asset price fluctuations. Greater economic policy uncertainty further leads to subpar business decisions. Economic sanctions, trade protectionism, and a geopolitical realignment of capital flows can bring closer asset market fragmentation. Many countries are eager to escape from the U.S. orbit. All of these fundamental forces still cannot erode the American dollar dominance over global finance, although some alternative currencies tend to play a more prominent role in regional trade and infrastructure. The Chinese Renminbi serves well numerous middle-income and low-income countries as part of the Belt-and-Road Initiative. The Euro continues to be the largest common denominator for trade transactions within the European Union even after Brexit. The Japanese Yen, Deutsche Mark, and Australian dollar each serve the regional markets well enough. These alternative currencies may or may not dethrone the American dollar in trade and finance worldwide in due course. Yet, these alternative currencies can cause asset market fragmentation in particular, and financial deglobalization in general, to persist in the current decade.

The global financial system is not just an abstract concept, but a unique entity that touches virtually every aspect of modern economic life. The global financial system governs how states, companies, and individual investors access and attract capital flows. In a liberal view of the world, capital determines the recurrence and reversal of fortune for economic growth, peace, and prosperity in different parts of the world. Specifically, new national payment systems and CBDC wire wallets are vital to fair trade, finance, cross-border commerce, and even technological development. The global financial system allows a significantly broader pool of people to share in the world’s wealth creation. At best, the global financial system has kept close its new rivals and competitors. Several recent world crises help reshape the current global financial system. In practice, many fundamental forces come into play. In light of recent wars and other potential military conflicts, geopolitical considerations often trump economic factors, diplomatic concerns, and technological advancements. In due course, both market forces and non-market considerations help secure some fragments of the global financial system. As a result, broader market fragmentation further extends financial deglobalization. After all, we can draw some vital lessons from these long prevalent and persistent mega trends in the global financial system. In this new light, both financial deglobalization and asset market fragmentation can cause profound policy implications for global trade, finance, and technology.

Financial and economic institutions have grown stronger and better able to insulate some middle-income countries from the global financial cycle. From China, Russia, and Japan to India, Switzerland, South Korea, and Taiwan, these countries have stockpiled substantial foreign-exchange reserves to better defend their currencies from speculative attacks and macrofinancial crises. In recent years, central banks have become more independent, and these central banks often try to focus on the long prevalent mandate of price stability with some explicit or implicit inflation target (2% or the broader range of 1% to 3%). During the most recent inflationary surge, monetary guardians in Australia, New Zealand, Brazil, Chile, Hong Kong, Hungary, Peru, Poland, and South Korea started their own interest rate hikes well before the Federal Reserve System and European Central Bank did so. All these efforts help curtail recent dramatic increases in retail prices and wages worldwide.

These recent developments have steadily chipped away at the U.S. dominant role in the global financial system. Meanwhile, East Asian capital controls have helped stave off financial fragility and macro instability that might arise from volatile capital inflows in due course. In practice, these capital inflows provide a natural source of patient capital for the fast-growing high-tech sectors in the region. In East Asia, the central banks and treasuries there coordinate and orchestrate their monetary and fiscal stimulus programs in support of national champions in some strategic sectors. These state guardians can accomplish much in close alignment with the homeland industrial policy stance without cutting off the East Asian region from global finance. Foreign capital continues to flow in and out of this region. The trademark logos of multinational corporations continue to adorn the skyscrapers in Beijing, Hong Kong, Tokyo, Taipei, Shanghai, Seoul, and Singapore.

Less benign is the second fundamental force reshaping the global financial system. Today, the U.S. and its western allies increasingly apply and leverage hefty tariffs, embargoes, foreign investment restrictions, and economic sanctions as some new form of strategic weapons against China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Economic warfare is not new and dates back at least as far as an Athenian ban on trade with its close neighbor Megara in 432 BC. Trackable electronic payments and the U.S. greenback combine to grant America a greater sphere of influence over world trade, finance, and even technology. With the centrality of U.S. big banks, the American dollar remains the largest common denominator in the vast majority of global trade transactions, wire transfers, and capital flows across key regions and jurisdictions around the world. With this rare unique economic power, the U.S. and its western allies are now able to cut banks, or entire regions, out of the global financial system. As a result, many non-U.S. banks, insurers, and other financial intermediaries seek alternatives to the American-driven levers of global finance.

The U.S. government tightened its firm grip over foreign finance in the wake of the heinous terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001. As the Treasury looked for robust ways to counter terrorist finance in support of future attacks, the Treasury alighted on the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the long prevalent global financial co-operative system whose fast messaging services facilitate cross-border payments and wire transfers etc. SWIFT data can help track trade transactions, and this monitor mechanism further helps reveal links between terrorists and financiers. The same sort of financial alignment allows the Treasury to find some other ties too, especially between foreign banks and countries under American sanctions (China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea). The Patriot Act serves as another product of the 9/11 attacks, and then grants the Treasury the power to drive such foreign banks out of business.

The Treasury applied, leveraged, and deployed this novel financial weapon against Macau’s Banco Delta Asia (BDA) in September 2005, and then once again against Latvia’s ABLV Bank in February 2018. Both times the real target was North Korea. The Treasury accused these banks of allowing North Korea to break international law, in part by helping to fund the nuclear-weapons program. In time, the Treasury considered designating each bank a prime money-laundering concern. Under the Patriot Act, this step can ban U.S. banks from providing all correspondent accounts to BDA and ABLV. In due course, these banks can no longer move dollars through the American-driven global financial system. The prohibition would stop both banks from processing dollar transactions for their clients. As a consequence, the Patriot Act effectively shuts these banks out of international finance. For the vast majority of other banks worldwide, they would risk Treasury designation as money launders themselves if they continue to do business with BDA and ABLV.

In due time, global banks withdrew their funds from both BDA and ABLV en masse. Within weeks of the Treasury’s announcements, each faced a liquidity crisis, and its regulator seized bank management soon after the fateful Treasury designation. In response to the recent Russia-Ukraine war in Eastern Europe, the Treasury can dole out the same treatment to any foreign banks and other financial institutions in support of Russia’s military-industrial base. In the broader context of financial de-globalization and asset market fragmentation, the Patriot Act redivides the global financial system into the U.S. and its western allies versus Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea.

The U.S. and its western allies have several other ways of cutting off their enemies from vital parts of the global financial system. Since 2008, American banks can no longer facilitate dollar trade transactions on behalf of foreign banks from Iran. This ban further applies to offshore dollar trade transactions outside America. Since the Russian invasion of Crimea in 2014, the U.S. economic sanctions prohibit Russia’s biggest banks from raising debt or equity capital in America and Europe. After 2022, the U.S. and its western allies further forbid a far greater array of dollar transactions in relation to Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea. Banks, insurers, and other non-bank financial institutions from these regimes fail to secure their parts of the global financial system through SWIFT. All of these recent bans continue to have knock-on effects beyond the U.S. borders. Around the world, more than 70% of financial institutions follow the U.S. blacklist of foreign entities as a guide for future business ties.

The increasingly tense economic rivalry between America and China is the third force reshaping the global financial system. Like Russia, China has set up its own payment networks and CBDC wire wallets. These alternative mechanisms are shut off from the U.S. and its western allies. As a result, these mechanisms help defang any future economic sanctions from the U.S. government.

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) continues to scrutinize inbound capital investments in relation to national security. In recent years, CFIUS reviewed 286 transactions, 2.5 times more transactions than about a decade ago. Further, CFIUS powers expanded to encompass global supply-chain security and technological leadership. Also, Britain started its own foreign investment screening regime in recent years for national security purposes. Specifically, Britain reviewed more than 850 transactions in accordance with the U.S. purposes of technological leadership in some strategic sectors, such as semiconductor microchip design and production, 5G high-speed cloud telecommunication, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, and the metaverse. In recent years, Japan followed suit to include the same strategic sectors as part of its foreign investment screening regime too. In a similar vein, the European Union now contemplates beefing up its own foreign investment screening rules in close alignment with America, Britain, and Japan.

In America, the Treasury vets foreign investments in some sensitive technological advances in semiconductor wafer design, quantum computing infrastructure, and generative AI with virtual robots, avatars, and other large language models (LLM). For the CFIUS and Treasury, the main countries of concern include China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. At any rate, national security and technological leadership collectively trump investment returns. The CFIUS and Treasury can only screen a relatively narrow range of strategic sectors (in accordance with the new homeland industrial policy stance). In many western countries, domestic political calculations may significantly ratchet up regulatory scrutiny, protection, and insulation against foreign investments.

The longer-term policy implications of such fragmentation may turn out to be fresh worries for the world economy. Free capital flows usually ensure higher investment returns for stock market investors and multinational corporations. Amid geopolitical strife, the reversal of these capital flows can cause all sorts of problems. The abrupt and sudden withdrawal of foreign capital often triggers crashes in asset prices and returns, threatens macrofinancial stability, and causes a near-term flight to higher-quality assets for the foreseeable future. Short-term capital shortages can further make countries more prone to external shocks, by removing the broader ability to diversify risks worldwide. In recent years, cross-border capital flows have declined precipitously. Today, residual capital flows increasingly re-orient along geopolitical lines.

Re-prioritizing national security above free-market investments now reshapes free capital flows across national borders. Global capital flows, especially foreign direct investments (FDI), have plunged precipitously, and now reorient along geopolitical lines. As some geopolitical blocs and regions pull further apart, it is quite likely for many states to make the world poorer than it otherwise would be. In recent years, the trade war between the U.S. and China seems to redivide the global economy into the U.S. and its western allies and trade partners vis-à-vis China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Geopolitical alignment often dictates and reinforces asset market fragmentation in the wider context of financial deglobalization.

Cross-border capital flows come from asset market portfolio positions, bank loans, and FDIs. All these types of capital flows fell soon after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, and these capital flows have yet to recover in the next few years. In fact, the decline in FDI became sharper after the onset of the American trade war against China. As a fraction of global GDP, global FDI had fallen from an average of 3.3% in the early-2000s to well below 1.5% in recent years. After Russia invaded Ukraine in Eastern Europe, cross-border bank loans and debt capital flows fell by 25% to 55% respectively to those countries that had supported Russia in UN votes. A recent IMF survey shows a strong positive correlation between free capital flows and significant decreases in economic policy uncertainty, primarily due to the slow, gradual, and progressive relaxation of geopolitical tensions between the U.S. and China.

The same IMF survey analyzes 300,000 new greenfield cross-border investments in the recent decade from 2015 to 2024. This survey shows a significant decline in FDI flows to China soon after its bilateral trade tensions with America ratcheted up in recent years. Specifically, China-bound FDI flows in some strategic sectors fell by more than 55%. Strategic FDI flows to Europe and East Asia fell too, but by no more than 15%. In comparison, strategic FDI flows to America remained relatively stable over the same data span. Around the world, average FDI flows declined by about 20%, but this decline was extremely uneven across different trade blocs and regions. The U.S. and its close allies and trade partners in Western Europe came out as relative winners. FDI flows to China and East Asia fell significantly by much more than the aggregate decline.

In recent years, geopolitical alignment plays a vital role in routing free capital flows. Another IMF study shows that the fraction of FDI flows between geopolitically close countries has risen significantly over the past decade. Also, geopolitical proximity is more important than the geopolitical sort. The same correlation with geo-political alignment is present for cross-border bank loans and equity capital flows. For these reasons, geopolitical alignment has become a vital non-market force in global trade, finance, and even technology.

Like free trade, free capital flows should theoretically provide greater opportunities for both businesses and investors to enjoy better wealth creation. Long-run capital investments from multinational companies further boost technological innovations, corporate networks, and best practices and experiences in business management. Foreign capital flows help fund any gap in corporate finance for both multinational corporations and small-to-medium enterprises (SME). This wider dependence on FDI flows is especially acute in many countries where the regional financial system relies heavily on bank loans and debt capital issuances. If global capital is free to move across borders, investors would expect to see a generic decrease in the cost of capital worldwide.

Despite the vast scale of financial globalization over the past 35 years, with gross cross-border positions rising from 115% of world GDP in 1990 to 374% in 2024, it would be quite elusive to measure real gains in light of free capital flows. Empirical studies show that sudden inflows of foreign capital can cause financial crises. The sudden FDI flows often sow the seeds for subsequent financial crises in the forms of high inflation, sharp currency devaluation, and systemic bank failure resolution. Specifically, a recent IMF survey delves into more than 150 credit-boom episodes of unusually high capital flows across 53 middle-income and low-income countries from 1980 to 2024. About 20% of these credit-boom episodes led to systemic bank failures and crises within 2 years of the credit boom. Another 25% of these credit-boom episodes resulted in currency crises. Stock market crashes tended to be in sync with these financial crises. Sharpe declines in asset prices and returns usually clustered around these global financial convulsions. It is difficult for global investors to dismiss the strong correlation between sudden FDI flows and subsequent credit growth, high inflation, currency devaluation, and bank failure resolution.

Today, the global financial system seems to splinter into separate FDI blocs for the U.S. and its western allies vis-à-vis China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Several other high-population countries such as Brazil, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines have yet to demonstrate their own geopolitical alignment. The resultant hit to global GDP is almost 1% after 5 years, and more than 2% in the longer term. The lost world growth concentrates in the 2 main trade blocs between the U.S. and China. The other countries with no clear geopolitical alignment may stand a chance to benefit from greater global market integration. However, these residual countries may need to withstand short-term pains when they decide to join one of the major trade blocs, the American-driven Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) versus the China-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). In the meantime, the major difference between the CPTPP and the RCEP is that the CPTPP further contains major provisos in support of high foreign labor standards, net-zero carbon emissions for better environmental protection, intellectual property rights, and state subsidies, tax rebates, and several other incentives for state enterprises in some strategic sectors. When push comes to shove, geopolitical alignment can dictate how recent asset market fragmentation reinforces broader financial deglobalization.

It has been an easy call for the U.S. and its western allies to remove Russian banks from the major networks of SWIFT since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. This measure severs a vital artery connecting Russian banks to the global financial system. This measure effectively adds to a battery of economic sanctions against the Russian economy. Since the U.S. and its western allies imposed key economic sanctions against Russia in response to the Russia-Ukraine war, the vast majority of Russian banks have been unable to make cross-border retail payments and wire transfers in the American dollar.

However, the Putin administration had the prescience to prepare its own financial system for the worst-case scenario. Since Russia’s invasion of Crimea and eastern Ukraine back in 2014, Russian banks have been trying to develop their own unique payment systems. The System for Transfer of Financial Messages (STFM) serves as the Russian equivalent of the SWIFT interbank wire transfer system worldwide. In addition, Russian banks apply and leverage their own new card-payment system, Mir, to replace several western credit card providers such as Visa, Mastercard, and American Express. Although the American-driven sanctions cut off Russian banks from the global financial system since Russia launched a war against Ukraine back in 2022, Russian banks and corporate treasuries continue to facilitate cross-border transfers and transactions in alternative currencies with some help from Russia’s major trade partners China, India, Iran, North Korea, and Turkey. A friend in need is a friend indeed.

In China, the systemic banks have been developing their own Cross-border Inter-bank Payment System (CIPS) as a feasible alternative payment settlement system to SWIFT since 2015 (almost 2 years after China launched the ambitious Belt-and-Road Initiative). As of early-2024, more than 1,500 banks, insurers, and other non-bank financial institutions use CIPS. These banks represent no more than 15% of SWIFT global membership of more than 11,500 financial intermediaries. However, the current CIPS users include 30 Russian banks. As a result, this leverage further reduces the adverse impact of western sanctions on Russian banks because these banks can alternatively make cross-border payments in Chinese Yuan (Renminbi). Meanwhile, CIPS processes $70 billion cross-border payments and wire transfers per day. By comparison, SWIFT processes $35 trillion cross-border payments and wire transfers per day. Nonetheless, if the CIPS continues to grow its membership worldwide, network effects would harness the potential to prompt explosive growth in worldwide wire transfers and retail payments through the CIPS.

At the same time, China’s retail payment providers have grown to rival key western incumbents such as Visa, Mastercard, and American Express. The Chinese credit card network, UnionPay, is now the world’s largest network by transaction volume and is available as a low-cost credit card in 183 countries. The dual digital payment services, Alipay and WeChat Pay, now each collaborate with more than 80 million merchants worldwide. In comparison, Visa collaborates with 100 million merchants worldwide.

In India, the new Uniform Payments Interface (UPI) has been growing rapidly since 2016. Today, the UPI processes about $1.8 trillion cross-border payments and wire transfers per year, or more than 50% of total GDP in India. The UPI now accounts for more than 75% of India’s digital retail payments. A recent PwC survey suggests that this fraction can rise to more than 90% in the next few years (even as the total volume of digital retail payments quadruples in India).

The UPI allows each user to make fast and cost-free payments by sending a text message or scanning a QR code. In practice, the UPI has made modern life much safer, simpler, and cheaper for both businesses and consumers up and down the caste system in India. In support of India’s state welfare system, the UPI leverages a rare revolutionary digital-identity system to make fast and secure fiscal transfers, subsidies, tax rebates, and other cash incentives. In India, hundreds of millions of people can now receive direct benefit transfers to bank accounts with their unique digital identification codes, in lieu of physical cash transfers. No corrupt bureaucrat can siphon off such secure payments because the UPI streamlines the distribution of fiscal transfers and short-term social emergency funds, as during the Covid-19 pandemic years. Around the world, the UPI expands into many other countries with simple text messages and QR codes, such as Australia, New Zealand, Germany, France, Canada, USA, UK, UAE, Saudi Arabia, Brazil, Chile, Singapore, Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand, South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines.

Meanwhile, India continues to apply the technology behind its digital infrastructure to increase its influence abroad. Since 2018, India’s Modular Open Source Identity Platform (MOSIP), a non-profit organization in Bangalore, has made a new version of the codes in support of the UPI digital-identity system worldwide. This brave new digital public infrastructure can go beyond mobile payments to include health-care records, public-sector budgets, and public utilities such as clean water, natural gas, and electricity. India now attempts to make the UPI and MOSIP more interoperable across multiple alternative platforms worldwide. In due course, the resultant global connections can create a completely Indian-run alternative wire transfer system to SWIFT and CIPS beyond the control of either America or China.

The world economy now needs a level playing field for new competitive pressures, technological innovations, and asset market frictions in national payment systems. From the UPI to CIPS, these technological innovations serve as alternative service improvements to SWIFT. As a result, the recent proliferation of worldwide payment networks can benefit not only the countries of both origin and deployment, but also more importantly, the broader global financial system.

Yet, these mobile payment networks, digital identity systems, and fintech platforms further cause and reinforce the new risk of asset market fragmentation. Given their uses for evading the scrutiny of geopolitical rivals, governments may not resist the temptation to force domestic merchants and consumers to stick to their own fintech payment platforms, possibly with dramatically fewer and weaker positive network effects worldwide.

SWIFT continues to play a prominent role in linking up national payment systems. After all, the main obstacle to broad user adoption is technical because every new network applies its own standards and protocols for data encryption, authentication, security, and privacy protection etc. The deployment costs often rise substantially when big banks and tech titans seek to operate across multiple payment networks, since these institutions should maintain separate equity capital pools on each one. With multiple interoperable payment networks, digital identity systems, and fintech platforms, these institutions may become less able to net off transactions against each other. As a consequence, these institutions would need to move capital more often across countries, regions, and jurisdictions.

Outside America, the world has geopolitical, economic, and technological reasons to seek some strong alternative currencies to the U.S. dollar as the dominant global reserve currency. An erratic Washington can turn forecasting longer-run economic policy uncertainty, and thereby the American dollar’s relative strength, into a mug’s game. Politicians often engage in periodic stand-offs over whether the government should lift a cap on the national debt. As fiscal deficits accumulate on top of extant sovereign debt, the worst-case scenario triggers a short-term public-sector default. As a result, this default may endanger the current status of Treasury bonds as the safest high-quality asset class around the world. Over the past few years after the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, the Federal Reserve System strategically paces gradual interest rate hikes to help tame inflation in light of dramatically higher prices almost everywhere. Meanwhile, the FOMC is likely to launch the next wave of interest rate cuts in response to the fact that core inflation progressively returns to the medium-term target of 2% in the wider target range of 1% to 3%. In terms of macro mandate implementation, the new tide turns from hawkish interest rate hikes to dovish rate cuts as the world economy enters the next episode of the global financial cycle in accordance with American monetary policy adjustments.

Despite the incentives for non-U.S. countries, banks, and multinational companies to shun the greenback, no other contender has come close to snatching the crown as the dominant global reserve currency. As the American dollar’s dominance over its nearest rivals has grown stronger than ever, the global financial system seems to experience asset market fragmentation of the second tier of reserve currencies. These alternative reserve currencies include the Euro, Deutsche Mark, Japanese Yen, British Pound, Swiss Franc, and Chinese Yuan (Renminbi). These currencies now each seem to serve some specific geopolitical trade blocs, zones, and regions respectively.

Since the turn of the new century, the proportion of global currency trades with the American dollar has held steady at 85% to 90%. A huge part of this ubiquity derives from the long prevalent use of the greenback as the largest common denominator in global payments, trade transactions, and capital flows across countries, regions, and jurisdictions. Another part of this ubiquity arises from the fact that the American dollar continues to play a prominent role for many foreign-exchange dealers. The foreign-exchange market benefits substantially when the American dollar, a single global reserve currency, takes this linchpin-like role, because this currency allows separate pools of near-term equity capital for less liquid counterparts to be part of the bigger group of dollar assets. Frequent currency trades with multiple currencies would cause unnecessary but avoidable transaction costs, interest rate risks, and asset market frictions.

In the meantime, central bank foreign-exchange reserves continue to show some common patterns in the currency split. Central banks use, apply, and leverage their foreign-exchange reserves to calm asset market turbulence during times of severe financial stress. For better diversification, central bank foreign-exchange reserves should comprise a reasonable mixture of alternative currencies for the major trade partners. All of these reasons, market forces, and incentives help ensure that the American dollar wins in both the pervasive use and allocation of foreign-exchange reserves for many central banks around the world.

In response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the American dollar preponderance has held reasonably well in the face of the western immobilization of the Central Bank of Russia’s foreign-exchange reserves. In response to the U.S. bilateral trade war against China, the Treasury rakes in hefty tariffs on imports from China in support of a stronger American dollar. The primary U.S. geopolitical rivals, specifically, Russia and China, might seek some alternative reserve currencies to the American dollar. Yet, no alternative long prevalent hard currencies can match the American dollar’s dominance, liquidity, ubiquity, and universality in global trade, finance, and even technology.

The American dollar looks durable in some other ways. Aggregate demand helps reduce interest rates on dollar debt. This rare unique feature makes the American dollar the first choice for multinational corporations and governments, both of which often need to borrow in foreign currencies to facilitate cross-border trade sanctions, payments, and capital flows. Today, the American dollar continues to be the largest common denominator for well more than half of cross-border bank loans and debt securities. Around the world, banks, insurers, and other financial institutions keep the common faith that the Federal Reserve System has more firepower than other central banks. This common faith ensures that the American dollar strengthens in a major crisis, even if the worst of the trouble emanates from America itself (as in the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis and subsequent Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009). The pervasive belief is that dollar assets, especially Treasury bonds, often serve as safer collateral than many other alternative currencies.

Recent efforts to promote whizzier alternative currencies seem to have faltered in both form and substance. From Bitcoin to Ethereum, cryptocurrencies are subject to extreme fluctuations in real-time asset market valuation. For this reason, these cryptocurrencies often fail to serve as reliable stores of value, proper mediums of exchange, and stable units of account in terms of the 3 vital functions for fiat money. The digital stablecoins that have overcome this deficiency through pegs to proper currencies can prove to be more useful. However, only those stablecoins that peg to the American dollar have dramatically gained widespread user adoption.

In the current modern era of digital revolutions, central banks gradually start to mint their unique digital currencies. Even if these central bank digital currencies (CBDC) take off, governments would need to ensure sufficiently high interoperability across multiple payment networks, low-cost convenience for fiscal transfers and domestic users, and distinctive competitive advantages over the American dollar. In the best likelihood of success, the American dollar would continue to serve as the dominant global reserve currency for the foreseeable future.

Geopolitical conflicts and tensions further continue to spur the recent asset market fragmentation of capital flows, payment networks, and financial institutions. A sole global financial system is neither necessary nor sufficient for worldwide peace and prosperity. As financial deglobalization and asset market fragmentation chip away at the vital roles of both the American dollar and government influence in the global financial system, both Beijing and Washington might regret losing positive bilateral business opportunities, connections, and dual representations in world affairs.

However, these recent developments can make economic warfare more feasible. At the same time, these recent developments often normalize the sense of conflict between some countries, regions, and jurisdictions. In addition to geopolitical risks, conflicts, and tensions, the new homeland industrial policy stance tilts toward tight control over state subsidies, tax rebates, and other economic incentives in support of national champions in some strategic sectors. Through hefty tariffs, embargoes, investment restrictions, and many other economic sanctions, trade protectionism may inadvertently exacerbate asset market frictions between both friends and foes abroad. Multinational corporations often throw up financial firewalls themselves as these companies adapt to each new wave of sanctions. Economic integration may not ensure global peace and prosperity. Moreover, if the U.S. and its western allies increasingly shoulder the costs of disengagement, the marginal cost of economic warfare continues to fall in due course.

In recent years, the Bank of England prescribes a new macro-financial stress test. An abrupt crystallization of geopolitical tensions can cause a sharp deterioration in market expectations of economic fundamental forces. Stock prices tank, volatility explodes, and investors scramble to de-risk their asset portfolios worldwide. As a consequence, some sovereign wealth funds start offloading American, British, and European government bonds and bills. This sovereign debt turmoil may lead to the next global financial crisis.

In both Beijing and Washington, policymakers would probably stiffen cross-border trade and investment barriers to prevent domestic companies from sending capital anywhere in favor of foreign rivals and competitors worldwide. Among geopolitical trade blocs, zones, and regions, capital flows would dry up further. The same logic further applies to global payments too. In effect, asset market fragmentation would inevitably divide the world into separate spheres of influence over global payments. This division would accelerate the faster exponential growth and user adoption of China’s CIPS and India’s UPI payment networks as alternatives to SWIFT. In time, these disruptive innovations export new open-source payment systems, and these payment systems interoperate with alternative currencies as fair substitutes for the American dollar, the latter of which remains the dominant global reserve currency.

Re-prioritizing national security above free-market investments now reshapes free capital flows across national borders. Global capital flows, especially foreign direct investments (FDI), have plunged precipitously, and now reorient along geopolitical lines. As some geopolitical blocs and regions pull further apart, it is quite likely for many states to make the world poorer than it otherwise would be. In recent years, the trade war between the U.S. and China seems to redivide the global economy into the U.S. and its western allies and trade partners vis-à-vis China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea. Geopolitical alignment often dictates and reinforces asset market fragmentation in the broader context of financial deglobalization.

As of mid-2025, we provide our proprietary dynamic conditional alphas for the U.S. top tech titans Meta, Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon (MAMGA). Our unique proprietary alpha stock signals enable both institutional investors and retail traders to better balance their key stock portfolios. This delicate balance helps gauge each alpha, or the supernormal excess stock return to the smart beta stock investment portfolio strategy. This proprietary strategy minimizes beta exposure to size, value, momentum, asset growth, cash operating profitability, and the market risk premium. Our unique proprietary algorithmic system for asset return prediction relies on U.S. trademark and patent protection and enforcement.

Our unique algorithmic system for asset return prediction includes 6 fundamental factors such as size, value, momentum, asset growth, profitability, and market risk exposure.

Our proprietary alpha stock investment model outperforms the major stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq. We implement our proprietary alpha investment model for U.S. stock signals. A comprehensive model description is available on our AYA fintech network platform. Our U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) patent publication is available on the World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) official website.

Our core proprietary algorithmic alpha stock investment model estimates long-term abnormal returns for U.S. individual stocks and then ranks these individual stocks in accordance with their dynamic conditional alphas. Most virtual members follow these dynamic conditional alphas or proprietary stock signals to trade U.S. stocks on our AYA fintech network platform. For the recent period from February 2017 to February 2022, our algorithmic alpha stock investment model outperforms the vast majority of global stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI USA, MSCI Europe, MSCI World, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq etc.

With U.S. fintech patent approval, accreditation, and protection for 20 years, our AYA fintech network platform provides proprietary alpha stock signals and personal finance tools for stock market investors worldwide.

We build, design, and delve into our new and non-obvious proprietary algorithmic system for smart asset return prediction and fintech network platform automation. Unlike our fintech rivals and competitors who chose to keep their proprietary algorithms in a black box, we open the black box by providing the free and complete disclosure of our U.S. fintech patent publication. In this rare unique fashion, we help stock market investors ferret out informative alpha stock signals in order to enrich their own stock market investment portfolios. With no need to crunch data over an extensive period of time, our freemium members pick and choose their own alpha stock signals for profitable investment opportunities in the U.S. stock market.

Smart investors can consult our proprietary alpha stock signals to ferret out rare opportunities for transient stock market undervaluation. Our analytic reports help many stock market investors better understand global macro trends in trade, finance, technology, and so forth. Most investors can combine our proprietary alpha stock signals with broader and deeper macro financial knowledge to win in the stock market.

Through our proprietary alpha stock signals and personal finance tools, we can help stock market investors achieve their near-term and longer-term financial goals. High-quality stock market investment decisions can help investors attain the near-term goals of buying a smartphone, a car, a house, good health care, and many more. Also, these high-quality stock market investment decisions can further help investors attain the longer-term goals of saving for travel, passive income, retirement, self-employment, and college education for children. Our AYA fintech network platform empowers stock market investors through better social integration, education, and technology.

Andy Yeh (online brief biography)

Co-Chair

AYA fintech network platform

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone’s first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2018-10-21 14:40:00 Sunday ET

President Trump floats generous 10% tax cuts for the U.S. middle class ahead of the November 2018 mid-term elections. Republican senators, congressmen, and

2020-05-21 11:30:00 Thursday ET

Most blue-ocean strategists shift fundamental focus from current competitors to alternative non-customers with new market space. W. Chan Kim and Renee Ma

2018-12-01 11:37:00 Saturday ET

As the solo author of the books Millionaire Next Door and Richer Than Millionaire, William Danko shares 3 top secrets for *better wealth creation*. True pro

2022-10-05 08:24:00 Wednesday ET

Precautionary-motive and agency reasons for corporate cash management Bates, Kahle, and Stulz (JF 2009) empirically find that public firms have doubled t

2017-10-09 09:34:00 Monday ET

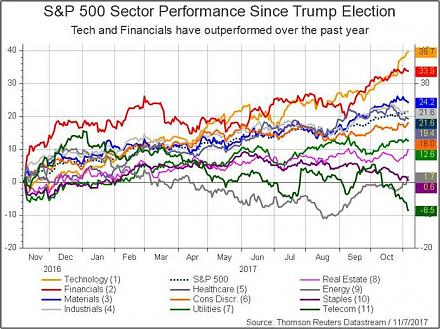

The current Trump stock market rally has been impressive from November 2016 to October 2017. S&P 500 has risen by 21.1% since the 2016 presidential elec

2017-04-01 06:40:00 Saturday ET

With the current interest rate hike, large banks and insurance companies are likely to benefit from higher equity risk premiums and interest rate spreads.