2023-12-10 09:23:00 Sun ET

stock market technology competition free trade fair trade multilateralism neoliberalism regulation compliance economic growth asset management finance federalism congress supreme court inclusive institutions

A given country is federal when both of its national and sub-national governments exercise separate and autonomous authority, both elect their own governors and legislators, and both tax their citizens for the non-exclusive and non-rivalrous provision of public goods (such as national defense, security, law enforcement, education, and infrastructure etc). Federalism requires that a constitution guarantees the administrative, legislative, and judicial powers of the national and sub-national governments. No one can change this constitutional guarantee without the consent of both national and sub-national populations.

America, Canada, Australia, India, Germany, and Switzerland etc generally serve as federal governance systems, but Britain, France, Italy, and Sweden etc do not. Although these latter countries have local governments, they depend on the national government for their powers. These non-federal countries are unitary in the basic sense that the national government can act alone to alter-and-even-abolish the local governments. In contrast, a confederal system exercises the administrative, legislative, and judicial powers of the national government in association with local units of government.

There are more than 89,000 separate governments in America, more than 60,000 of which have the power to levy their own taxes. In America, there are states, counties, municipalities (cities, boroughs, and villages), school districts, and special districts. However, only the U.S. federal government and 50 states receive sovereign recognition in the U.S. Constitution. All local governments are sub-divisions of states. In due course, states create, alter, or abolish these local governments and sub-divisions by amending state laws or constitutions.

The American Founding Fathers understood that republican principles would not suffice to protect individual liberty. These principles include periodic general elections, representative government, and political equality. In fact, these republican principles may make elites more responsive to popular concerns, but these principles cannot protect masses (or the weaker party) from government deprivations of liberty or property. The American Founding Fathers emphasized that the great object of constitution was both to preserve popular government, and at the same time, to protect individuals from unjust majorities with special interests. The dependence on American people is, no doubt, the primary control of government, but human history and experience have taught mankind the necessity of auxiliary precautions.

Among the most important auxiliary precautions built by the U.S. Founding Fathers to control government was federalism. In effect, federalism serves as a major source of constraint on big government. The Founding Fathers sought to construct a governmental system with the notion of opposite rival interests. Intense competition from alternative governments and rival bureaucrats helps constrain the incumbent governments and bureaucrats. Today, American federalism continues to permit policy diversity. Under American federalism, no uniform policy straitjackets the whole nation, and each U.S. state need not conform to the same laws, rules, and regulations. Specifically, Washington bureaucrats do not always know best about what corporations should try to accomplish in high technology in Silicon Valley, California.

Federalism helps better manage policy conflict. Permitting states and communities to pursue their own policies reduces the social pressures that would build up in Washington if the U.S. federal government had to decide everything. Federalism allows American citizens to decide many laws, rules, and regulations at the state and local levels of government. In effect, U.S. federalism avoids applying uniform national policies throughout the country.

Federalism disperses power. From the federal government to many state governments, the widespread distribution of power generally adds to the U.S. protection against tyranny. To the extent that political pluralism thrives in America, state governments have contributed to this success. These state governments further provide a political base for the survival of the opposition party when it has lost general elections.

Federalism helps increase political participation. This greater political participation manifests in the form of more people who run for political office. Throughout America, about one million people hold some kind of political office in states, counties, cities, townships, school districts, and special districts. These local leaders are generally closer to the people than Washington bureaucrats. Public opinion polls show that Americans believe that their local governments are more manageable and responsive to popular grassroots than the federal government.

Federalism often improves efficiency. State and local governments help reduce bureaucracy, red tape, delay, and confusion that would otherwise prevail if the federal government applied uniform policies throughout the country. Efficiency gains manifest in the day-to-day activities and operations that local governments run to deal with regional security, garbage collection, sewage disposal, street maintenance, and general infrastructure such as roads, ports, and other transportation hubs. A central federal government would not be able to cope with these state and local development matters in an efficient and cost-effective manner.

Federalism often helps encourage policy responsiveness. Multiple competing state and local governments are more sensitive to citizen views than a central monopoly government. The existence of multiple local governments with different packages of costs and benefits allows a better match between citizen preferences and public policy. People and businesses often vote with their feet by relocating to those states and communities that most closely conform to their own policy preferences. Greater mobility not only facilitates a better match between citizen preferences and public policy, but this mobility also encourages competition among states and communities to offer better public services at lower costs.

Federalism encourages policy experimentation and innovation over time. Many Americans may perceive federalism as a rather conservative idea. However, federalism has long served as the instrument of progressivism. For example, the groundwork for the New Deal was built in state policy experimentation during the Progressive Era. Federal programs as diverse as income tax, unemployment compensation, countercyclical fiscal aid, bank deposit insurance, wage and hour legislation, Social Security, and food support all had antecedents at the state level. Much of the current liberal policy agenda (from health insurance and childcare to fiscal support of industrial research and development) has been the key policy priorities for various U.S. states. Specifically, the Affordable Care Act of 2010, often known as Obamacare, was the largest regulatory overhaul and expansion of U.S. mandatory health insurance coverage since Medicaid and Medicare in 1965. Under the Obama administration with Republican-led Congress, this non-incremental public health care policy reform applied to the entire country the prior policy experimentation of universal health care at the state level in Massachusetts (when Mitt Romney had served as Governor and Presidential Nominee in the Republican Party). The great progressive Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis used the compelling phrase, state-level laboratories of democracy, in defense of state experimentation with new solutions to social and economic problems.

Political conflict over federalism usually tends to follow ideologically liberal and conservative political cleavages. This political conflict focuses on the division of responsibilities between national and local governments. Generally, liberal proponents seek to enhance the power of the national government. These liberal proponents believe that the national government should exercise additional administrative, legislative, and judicial powers to enrich the social and economic lives of citizens with less discrimination, less poverty, more employment, and better health care. The federal government in Washington often has more powers and more resources than state and local governments have, and liberal proponents have turned to the federal government to cure the social and economic problems in America. A strong federal government can help ensure better uniformity of standards throughout the country. In reality, liberal proponents argue that state and local governments contribute to inequality in society by setting different services in health care, welfare, education, and other public functions.

Conservative proponents often seek to return administrative, legislative, and judicial powers to state and local governments. Adding to the powers of the federal government may or may not be an effective way of resolving the social and economic problems in America. On the contrary, conservative proponents argue that government is often the problem (but not the solution). Broadly, excessive regulation, burdensome taxation, and inflationary government expenditures combine to restrict citizen freedom with less effective incentives for economic growth, employment, and capital investment. In this conservative view, government should be kept small, controllable, and close to the people.

The case for centralizing policy decisions in Washington is almost always one of substituting the policy preferences of national elites for those alternative policy preferences of state and local bureaucrats. Even on constitutional grounds, national elites arguably better reflect the policy preferences of the American people. Rather, federal intervention becomes necessary only when the policy goals and priorities in Washington should prevail throughout the country too.

The federal government is more likely to reflect the long prevalent policy preferences of the strongest interest groups (than 89,000 state and local governments possibly can). The costs of rent-seeking at the federal level (or lobbying government for special subsidies, privileges, and protections) are substantially lower in Washington in relation to the benefits available from national legislation than the total costs of rent seeking at 89,000 sub-national centers. Moreover, the benefits of national legislation are comprehensive. A single act of Congress, a federal executive regulation, or a federal appellate court decision can achieve what would require the collective actions by hundreds or even thousands of state and local governments. Hence, the benefits of rent seeking at the federal level in Washington are substantially more than the costs.

The size of the national constituency permits interest groups to disperse the costs of special interests over a very broad constituency. Cost dispersal is the key to interest group success. If these costs become more diffuse, it would be irrational for individuals, each of whom might bear only a small fraction of these costs, to expend time, money, and energy to counter the claims of the special interests. Cost dispersal over the entire country better accommodates the strategies of special interest groups than the substantially smaller constituencies of state and local governments.

From the adoption of the Constitution of 1787 to the end of the Civil War of 1861-1865, the U.S. states were the most important units in the American federal system. Americans looked to the sub-national states for the provision of public services in response to most social and economic problems. State governments decided even the most controversial social issue of slavery at that time. Anti-federalists from Thomas Jefferson to John Calhoun, who defended slavery and secession, questioned the supremacy of the federal government in America.

The supremacy of the U.S. federal government was eventually set on the battlefields of the Civil War. For almost a half-century after this inland conflict, the federal government narrowly interpreted and exercised the trilateral administrative, legislative, and judicial powers, and the state governments continued to decide most domestic social and economic policy issues. In this dual federalism, the U.S. federal and state governments divided the vast majority of government functions and public services. The federal government concentrated attention on the trilateral powers in U.S. national defense, foreign diplomacy, trade, money, post office, infrastructure, and commerce across state borders etc. By comparison, state governments decided the important domestic social and economic policy issues such as education, health care, welfare, and criminal justice. This separation of policy responsibilities was like a layer cake, with local governments at the base, state governments in the middle, and the federal government at the top.

The distinction between the federal and state government responsibilities gradually eroded during the period from 1913 to 1964. The Industrial Revolution and 2 world wars transformed American federalism into U.S. cooperative federalism. In response to the Great Depression of the 1930s, state governors welcomed massive federal public infrastructure projects under President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal. In addition, the federal government intervened directly in economic affairs, labor relations, business practices, and agricultural imports and exports. Through its grants-in-aid, the federal government cooperate with the states in public assistance contracts, employment services, child welfare benefits, public residential housing services, urban renewal investment projects, highway construction contracts, and vocational education opportunities. In U.S. cooperative federalism, this merger of both federal and state government responsibilities was like a marble cake: as the inventor mixed colors in a marble cake, the U.S. federal and state governments mixed their public services and responsibilities in American cooperative federalism.

Over the years it was increasingly difficult to maintain the fiction that the federal government helped the states fulfill their domestic responsibilities. During the period from the mid-1960s to the early-1980s, America transformed the federal system into U.S. central federalism. By the time President Lyndon Johnson launched the Great Society in 1964, the federal system had set forth its own national goals. Almost all social and economic problems morphed into national problems in the American society. Under this central federalism, state governments responded to federal policy priorities in accordance with federal rules and regulations, which served as the conditions for federal grant money at that time.

In the 1980s, the Nixon administration further transformed the U.S. federal system into new federalism. This new federalism required inter-agency efforts to reverse the flow of power to Washington. In turn, this delegation returned many domestic policy responsibilities to state and local governments. President Ronald Reagan applied new federalism to design a series of proposals to reduce federal government involvement in domestic policy programs. Under his new federalism, the Reagan administration encouraged states and counties to undertake greater policy responsibilities themselves. These efforts included the consolidation of many categorical grant programs into fewer block grants from the federal government. As a result, this new federalism put an end to fiscal tax revenue allocation between the federal and state governments. The state governments became less reliant on federal tax revenue and grant programs.

From the mid-1980s to present, representative federalism prevailed in the American society. In this U.S. representative federalism, there need not be a constitutional division of powers between the federal and state governments. The states play the important role of electing U.S. senators, members of Congress, and the president. The U.S. retains a federal system because the national bureaucrats are periodically chosen from sub-units of government: the president through the allocation of electoral college votes to the states, and U.S. Congress through the allocation of 2 Senate seats per state and the apportionment of representatives on the basis of state population.

In the landmark 1985 Garcia decision, the U.S. Supreme Court removed all barriers to direct congressional legislation in domestic matters that the federal system traditionally reserved to the state governments. The case arose after Congress directly ordered the state and local governments to pay minimum wages to their employees. In a landmark precedent, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed earlier decisions that Congress could not legislate state and local government matters. The Supreme Court further dismissed arguments that U.S. federalism and the Tenth Amendment prevented Congress from directly legislating state affairs. The Supreme Court ruled that the only protection for state powers was to be found in the states’ important role in electing U.S. senators, members of Congress, and the president under U.S. representative federalism.

The Supreme Court rhetorically endorses a federal system in the 1985 Garcia decision, but then leaves it up to the national Congress, rather than the Constitution or the U.S. courts, to decide what powers the federal and state governments should exercise in due course. Since the U.S. retains representative federalism in domestic institutional arrangements, the U.S. Constitution must divide powers, not the Congress. In this federal system, the states’ role is a matter of constitutional law, not legislative grace. In favor of representative federalism, this decision rejects almost 200 years of the constitutional status of U.S. federalism.

The supremacy of federal laws over state laws permits Congress to decide whether there is preemption of state laws in a particular field by federal laws. In total preemption, the federal government assumes all regulatory powers in a particular field, airlines, railroads, copyrights, and business receiverships etc. Partial preemption usually stipulates that a state law is valid as long as this state law does not conflict with the federal law in the same field. For example, the federal Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA) of 1970 specifically allows the state regulation of any occupational safety or health issues. Once OSHA enacts new standards, these standards would supersede all state standards. Another form of partial preemption, the standard partial preemption, permits states to regulate activities in a field that the federal government already regulates, as long as state regulatory standards are at least as stringent as those standards of the federal government. A good example is the federal Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). All state environmental regulations should at least meet, or should exceed, EPA standards in practice.

In 1995, devolution became a popular catch word in America with new Republican majorities in both upper and lower chambers of U.S. Congress. Devolution meant passing down policy responsibilities from the federal government to the states, and the U.S. welfare reform turned out to be the key to devolution. Since the New Deal under the Roosevelt administration, low-income mothers and children had enjoyed a federal entitlement to welfare benefits. In 1996, President Bill Clinton signed the new welfare reform bill into law with congressional approval (after 2 earlier presidential vetoes). This legislation turned over responsibility for determining eligibility for cash aid to the states. As a result, this law ended the 60-year federal entitlement. States would place a 2-year limit and a 5-year lifetime limit on all cash benefits. This reform was a major and non-incremental change in U.S. federal welfare.

Recent decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court suggest at least a partial revival of the original constitutional design of federalism. In 1995, the Supreme Court issued a first opinion in more than 60 years that recognized a limit on Congress’s power over inter-state commerce. This opinion reiterated and reaffirmed the Founding Fathers’ notion of a national government with only the powers set forth in the U.S. Constitution. The Supreme Court found that the federal Gun-Free School Zones Act was unconstitutional because this act exceeded congressional powers under the Interstate Commerce Clause.

The Supreme Court further invalidated a provision of a highly popular law of Congress, the Brady Handgun Violence Protection Act. In 1997, the Supreme Court decided that the law’s command to law enforcement officers to conduct background checks on all gun purchasers violated the very principle of separate state sovereignty. In 2000, the Supreme Court further held that the new Violence Against Women Act was an unconstitutional extension of federal power into the police powers of states. The Constitution requires a distinction between what is truly national and what is truly local. There is no better example of the police power, which the Founding Fathers undeniably left to the states and denied the central government, than the suppression of violent crime. The subsequent replacement of justices might reverse this current trend toward federalism by the Supreme Court.

Since 2010, health care (Medicare and Medicaid), welfare (income security), and education represent more than 80% of federal grants to state and local governments. Education is by far the most expensive public function of state and local governments. Education accounts for about 35% of all state and local government expenditures throughout America. Most of this money goes to elementary and secondary schools, but about 9% of nation-wide money goes to state universities and community colleges. In addition to education, welfare, health care, and transportation place a heavy financial burden on U.S. states and communities. In recent years, economic research shows that public policies tend to closely relate to the level of economic resources in a society. There is an empirically positive correlation between U.S. state government expenditures on education and state-level per capita income. Either state-level educational attainment helps attain better economic success, or greater state-level per capita income induces state governments to spend more on education. This virtuous cycle has been a long prevalent and pervasive economic phenomenon in U.S. federalism.

In her recent book, Primary Politics, Elaine Kamarck describes in detail the U.S. presidential election process. The U.S. presidential election process reflects the importance of American federalism during the U.S. establishment as an independent and separate sovereign nation in the 1780s-1790s. In America, both the presidential and congressional elections are state-run, as the U.S. founding fathers enshrined state authority over elections in the Constitution. In this broader context, U.S. state law governs the vast majority of technical aspects of U.S. elections, such as both candidate and voter eligibility, state administration of elections, and the state primaries.

The presidential election typically begins with state primaries. In each state primary (among Democrats or Republicans), voters choose each party’s presidential nominee. The primary results determine the allocation of delegates to each candidate. Within each party, delegates are individuals who vote on behalf of a group of people, and are often early supporters of a particular candidate, local party leaders, or party activists. Candidates accumulate delegates throughout the primary season that runs from January to June of the election year. After the last primary, the Democratic and Republican parties host national conventions. During these conventions, the parties officially nominate the presidential candidates who won the majority of delegates through the primary season.

During the general election, voters cast their votes for their preferable presidential candidate, although they indeed vote for the candidate’s slate of electors, who are generally chosen by the state party leaders. Americans elect the president through the Electoral-College process. The U.S. Electoral-College comprises 538 electors, and the presidential candidate who wins 270 electoral votes in November becomes the U.S. president-elect. In about mid-December, the Electoral College meets to confirm the election outcome in support of the new president. In accordance with U.S. federalism, this Electoral-College process differs dramatically from proportional representation in many western liberal democracies with parliamentary systems.

In terms of the presidential nomination process, the political parties control this process, and the Supreme Court protects this important role of Democrats and Republicans. Specifically, the Supreme Court has stated that the First Amendment’s freedom of association supports this important role of the parties. Over about 100 years, the presidential nomination process was a party-run system. In 1972, the state primaries began to select presidential candidates. However, this fundamental shift arose not from a change in law, but from a reform movement within the Democratic Party. This reform movement led to a basic change in party rules that connected primary results to delegate selection. Later, the Republican Party further adopted this change.

Nowadays, the parties select delegates through state primaries, although state party leaders can still select delegates in a different way. At each national convention, the delegates vote to confirm their presidential candidate on behalf of state voters. Through the primary season, the candidate who wins the majority of delegates becomes the party’s presidential nominee. The Federal Election Commission and state capitals attest and ensure that the presidential nominees’ names automatically appear on ballots.

Early primary contests such as the Iowa Republican caucus and the New Hampshire primary for Democrats are more of a beauty contest for presidential candidates to generate greater publicity by actively debating a wide variety of policy issues and ideas. Through the primary season, delegates pledge to loyally support each Democratic or Republican party’s nominee, and the candidates themselves are quite intent to be careful with their delegate selection for obvious reasons.

The U.S. constitutional presumption that states run elections means that Congress may not be able to set a national primary day. This specification would require impossible agreement between all 50 state legislatures, 100 Democratic and Republican state parties, and the 2 national parties. The parties often like to exercise control over the nomination process, and each state party has its own views on the appropriate timetable for its primary, even as some local primary differences persist. At the core of U.S. elections, state politics prevail over the country.

At this stage, the presumptive presidential nominee has often been the person who won the early primaries. In some years, the race goes on until the final primaries in June, as was the case with Reagan and Ford in 1976, Carter and Kennedy in 1980, and Clinton and Obama in 2008. The delegate count continues to be top-of-mind. Delegates tend to accumulate in large quantities from Super Tuesday in March of the election year. A presidential candidate must win a majority of delegates to secure the party nomination. Party law governs up until Election Day. When the Electoral College meets to confirm the new president-elect in mid-December, the Constitution applies afterwards.

Unfortunately, the nationwide popular vote plays essentially no role in the U.S. presidential election process, because the American founding fathers enshrined the Electoral College in the Constitution. Each state shall appoint electors in accordance with state legislature. Now 48 states choose to award all their electors to the winner of the state popular vote. Over the past 3 decades, the winner of the nationwide popular vote failed to win the presidency only twice (Bush in 2000 and Trump in 2016). These exceptions to the rule of thumb reflect some dramatic shifts in the distribution of U.S. population over the last few decades. Indeed, the U.S. population used to be relatively evenly spread throughout the country. However, much of the U.S. population now lives in the major coastal cities, as the U.S. agricultural revolution took huge swaths of middle America. The Electoral College has not changed to reflect these dramatic shifts in the distribution of U.S. population.

In America, it is relatively difficult for a third party to play a significant role in the presidential election process. Political parties are useful because they serve as a shorthand for people to understand what each party represents (topical policy issues, special constituent interests, ideological shifts, cultural values, and so on). Most Americans generally know what they get when they vote Democrat or Republican. The U.S. electoral system presents a challenge to a third party, because U.S. voters usually have no idea what third-party candidates represent. The U.S. has a first-past-the-post electoral system, whereby Americans cast their votes and the candidate with the majority of Electoral College votes wins the election. By contrast, third parties play a prominent role in several parliamentary systems. On the basis of proportional representation, the parliamentary systems allocate seats in government and legislature on the basis of each party’s vote share. As a result, this allocation gives third-party candidates more bargaining power to push through their agendas with cabinet slots.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2020-07-19 09:25:00 Sunday ET

Senior business leaders can learn much from the lean production system with iterative continuous improvements at Toyota. Takehiko Harada (2015)

2019-10-29 13:36:00 Tuesday ET

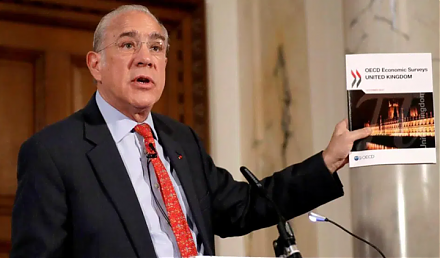

The OECD projects global growth to decline from 3.2% to 2.9% in the current fiscal year 2019-2020. This global economic growth projection represents the slo

2019-08-26 11:30:00 Monday ET

Partisanship matters more than the socioeconomic influence of the rich and elite interest groups. This new trend emerges from the recent empirical analysis

2018-06-25 12:43:00 Monday ET

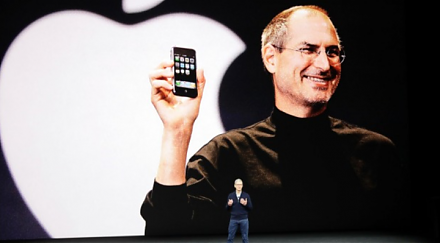

Apple and Samsung are the archrivals for the title of the world's top smart phone maker. The recent patent lawsuit settlement between Apple and Samsung

2025-06-05 00:00:00 Thursday ET

Former New York Times team journalist and Pulitzer Prize winner Charles Duhigg describes, discusses, and delves into how we can change our respective lives

2018-04-20 10:38:00 Friday ET

Allianz chairman Mohamed El-Erian bolsters a new American economic paradigm in lieu of the Washington consensus. The latter dominates the old school of thou