2023-08-21 12:25:00 Mon ET

patent trademark copyright adverse possession asymmetric information becker bentham bona fide purchase rule coase collective action contract contractual interpretation corrective taxation criminal law damage deterrence disclosure regulation due care eminent domain fault-driven liability finders-keepers rule first-party insurance good title hold-out problem imprisonment incapacitation injunction justice law and finance liability liability insurance litigation moral hazard negligence rule original ownership rule posner product liability property law public enforcement risk risk aversion settlement trial social norm social welfare strict liability tort law trade secret law utilitarianism

Steven Shavell (2004)

Foundations of economic analysis of law

Harvard Law School professor and director Steven Shavell presents his economic analysis of law in terms of the economic properties and consequences of both legal doctrines and institutions. Shavell delves into both the jurisprudence and normative adequacy of the neoclassic economic analysis of law with respect to the costs and benefits of legal rules, procedures, and institutions. Shavell focuses on 5 essential fields of law: property law, liability for accidents, contract law, litigation, and public enforcement and criminal law. This economic analysis of law seeks to identify the ripple effects of legal rules on the behaviors of relevant economic actors. From the normative viewpoint, this standard economic analysis of law further helps assess whether these ripple effects are socially desirable. This economic analysis of law stipulates that most economic actors are rational decision-makers. Thereby, these economic actors maximize their personal lifetime utility in response to legal carrots and sticks such as economic incentives and criminal sanctions etc.

Shavell further connects the social desirability of legal doctrines and precedents to the first and second fundamental theorems of social welfare. The first fundamental theorem of social welfare states that complete markets lead to the Pareto optimal allocation of economic goods and services with complete information and perfect competition. In this basic sense, no further market exchange would make a person better off without making another worse off. The second fundamental theorem of social welfare states that any Pareto optimum can be a competitive equilibrium for some initial set of endowments. The competitive market exchange can support any socially desirable Pareto optimal outcome. In this new light, some redistribution of initial wealth helps preserve Pareto efficiency in accordance with Bentham (1789) utilitarianism and Becker (1968) and Posner (1972) economic analysis of law and society in the more general sense. However, some specific attempts for the social planner to correct the original distribution of economic resources may inadvertently introduce economic distortions such as public goods, externalities, and information asymmetries etc. In this rare and unique case, complete Pareto optimality may not be attainable with social welfare redistribution.

Shavell focuses on the analytical foundations of 5 major subjects in the economic analysis of law: property, torts, contracts, litigation, and criminal law enforcement (Cooter and Ulen, 2003). Shavell omits some specific areas of law and economics such as antitrust law, taxation, and corporate law. Economic incentives and carrots and sticks tend to differ dramatically between the 5 major subjects and most other areas of law and economics.

Property rights furnish incentives to work well in practice. With property rights, most economic actors maintain durable goods and services. These property rights make trade possible. If such property rights were absent, economic actors would spend time and effort trying to take property from one another. In this fundamental sense, property rights would arise when their advantages become sufficiently large.

Property rights comprise possessory rights (of property use) and subsidiary rights to transfer possessory rights. An owner of land may not hold complete possessory rights as others may possess an easement to pass on his or her land. Also, others may retain the contingent right to take timber, or the contingent right to extract oil from the land. A rental agreement constitutes a division of property rights over time. Trust arrangements for adults to serve as property guardians of children can divide both the possessory rights and subsidiary rights to transfer property ownership. In essence, this division of property rights can be quite valuable when different parties derive different benefits from these property rights. The Coase theorem shows that property rights often flow to the economic actors who obtain the greatest economic efficiency gains from property rights. In this fundamental sense, the initial allocation of resources should not matter in the absence of transaction costs.

When it is socially desirable for the government to acquire property for public use, the government either purchases property or takes property through the exercise of the power of eminent domain. In the latter case, the law usually requires that the government should compensate property owners for the intrinsic value of what has been taken from them. Due to common errors in the state determination of property value, as well as concerns about the selfish behaviors of government officers, state purchase would be better than state confiscation and expropriation with economic rent compensation. On the other hand, the state sometimes has to assemble many contiguous parcels such as roads and bridges, some hold-out problems inevitably stymie property acquisition by state purchase. In the alternative scenario, it can be socially desirable for the government to exercise the power of eminent domain to take property for broader public use.

The law must determine the terms and conditions for economic actors to become legal property owners such as wild animals and oil deposits. Under the key finders-keepers rule, economic actors have incentives to capture new property rights when the search efforts are optimal for property ownership. These search efforts include the attempts to explore wild animals and oil deposits etc. If many economic actors seek new property rights at the same time, these economic actors invest excessive amounts of resources in new property search. In the worst-case scenario, several economic actors over-invest their search time and energy to the detriment of others in the same search journey. In order to curb excessive search efforts, government regulations should limit the quantities of wild animals or oil deposits etc. The usual trade barriers such as tariffs and quotas can serve as effective policy instruments for the socially optimal allocation of property rights in light of both better economic efficiency gains and social welfare transfers.

In association with the sale of property rights, a basic common difficulty relates to establishing the legally valid title of property ownership. Good title is important and essential for trade because buyers often seek legal assurance that their purchase decisions lead to the rock solid acquisition of property rights. Under a registration system, good title means that the owner becomes the title holder in the registry. In effect, good title passes at the time of sale by an official property ownership change in the registry. Thus, buyers can assess whether they obtain good title by checking the registry. In the absence of registries, the law applies the original ownership rule. In this case, the buyer acquires good title only if the seller provided good title in the first place. Alternatively, the buyer can acquire good title as long as he or she had reason to think that the sale was legitimate under the bona fide purchase rule. This waterfall approach helps most economic actors determine property sales and legal ownership transfers.

The legal doctrine of adverse possession allows involuntary transfer of land. Some economic actor can become the legal owner of land if he or she takes possession of this land for open private use over at least 10 years. In practice, a prospective adverse possessor might be able to bargain with the legal owner to rent-or-buy the land. Sometimes there may be good reasons for allowing such land to remain idle. The law therefore induces most legal owners to spend some resources in policing illicit trespass incursions. The law also discourages potential adverse possessors. Global economic history shows that the law allows a seller of land to establish good title to multiple prospective buyers in a cost-effective and efficient manner.

When economic actors use property, these people may cause positive or negative externalities in the form of costs or benefits to others. It is often socially desirable for economic actors to use property for reasons more than their own self-interests. In the best likelihood of success, economic actors should strive to increase positive externalities with no or low negative externalities. This cost-benefit analysis serves as the long prevalent keystone of economic analysis of property law. From time to time, the socially optimal resolution of harmful externalities often involves the inter-dependent behaviors of both victims and injurers. Victims often alter their locations in order to reduce their exposure to economic harm and social damage. It is often Pareto optimal for victims to seek compensation from injurers if the former can use new technological advances to reduce the adverse impact of harmful externalities. For instance, victims install air and water filters to avoid pollution, and then injurers should compensate victims by paying for high-tech usage at reasonable costs. The basic tenet concerns both economic efficiency and social welfare redistribution.

Legal intervention can address harmful externalities. A major form of intervention involves direct regulation. Through direct regulation, the state restricts permissible behaviors. For example, the state can require factories to use smoke arrestors. In the form of an injunction, victims can enlist the state power to force injurers to take major steps to prevent harm. A cease-and-desist letter sometimes suffices to warn potential injurers. In most cases, financial incentives often induce injurers to reduce harmful externalities. Under the corrective tax system, injurers pay the government some dollar amount that would be commensurate with the likely economic harm of (for instance) discharging pollutants into a nearby lake or river. In accordance with the Coase theorem, victims can sometimes have the opportunity to make mutually beneficial agreements with injurers who cause the harmful externalities.

Information asymmetries sometimes arise when the government grants intellectual property rights. The official approval of patents for inventions, copyrights for written works, or trademarks for corporate brand logos can simultaneously involve some major social benefit and some major social cost. The social benefit results from the economic advantage of inventions, written works, or brand names etc. Meanwhile, the social cost often results from the creation of market power for new tech titans and unicorns to price products or services well above marginal costs. Patent and trademark laws help assess how the legal rules and doctrines reflect the trade-off between the major social costs and benefits of intellectual property infringement.

A distinct form of legal protection is trade secret law. Trade secret law comprises several doctrines of contract and tort laws that help protect a reasonable range of commercially valuable information such as client segmentation. As an alternative arrangement for intellectual property rights, the government offers rewards to both the creators and inventors of knowledge-intensive intellectual property. Specifically, the author of a new book would receive some royalty rewards from the government for writing the book (possibly on the basis of sales worldwide). This system would create incentives for the creation of intellectual property with no price distortions.

Tort law governs the legal liability for accidents with a duty of care outside contracts. Through tort law, society reduces the risk of harm by threatening potential injurers with having to pay for those harms and damages in the presence of clear causation. Legal liability for accidents often serves as a core device for compensating victims. Under strict liability, injurers must always pay for harm only when he or she proves to be negligent. In this fundamental sense, injurers tend to owe a standard duty of care chosen by the courts. In practice, this negligence rule serves as the dominant form of liability for accidents. Strict liability for accidents specifically applies to some dangerous activities (which may often cause unforeseen harms and damages).

Another extension of legal liability for accidents concerns product liability. Product liability refers to the liability of companies for harms that their customers suffer due to some knowledge of risk. Here the degree of liability for accidents creates some incentives for companies to reduce risk. If customer knowledge is imperfect, there is an essential and important role for companies to reduce the risk of harm and so legal liability for accidents.

In most cases, both potential victims and injurers share the risk of harm. Potential victims may face the risk of accident losses. Potential injurers may face the risk of legal liability for accidents. Sometimes potential victims can mitigate the former risk via first-party insurance for specific accidents, and potential injurers can avoid the latter risk via liability insurance. Because risk-averse economic actors tend to buy insurance, the financial incentives cannot function directly in association with legal liability for accidents. If potential injurers are risk-averse and many liability insurers can observe the levels of due care by injurers, these potential injurers can buy full liability insurance coverage. In this case, their insurance premiums depend on the levels of due care by potential injurers. Nonetheless, if most liability insurers cannot observe the levels of due care by injurers, many liability insurance policies with full coverage may inadvertently pose severe moral hazard. In the worst-case scenario of market failure, no one buys such insurance products. Instead, as we can deduce from the theory of insurance, the common amount of insurance coverage becomes partial. This partial insurance coverage leaves potential injurers with key incentives to reduce the risk of harm. Therefore, the liability rule leads to direct incentives for most potential injurers to take care because these injurers bear some risk after the partial purchase of liability insurance. Notwithstanding the moral hazard problem, the sale of liability insurance is socially desirable in most basic models of accidents. The presence of insurance suggests that the tort system cannot serve as a primary market mechanism of compensating risk-averse victims against harms and losses. In significant part, the legal justification for the tort system must relate to incentives that partial insurance creates to help reduce risk. Both strict liability and insurance can compensate victims, but the former often turns out to be more expensive than the latter. In most cases, it would be better for the government to complement the strict liability system with insurance in order to accomplish fair compensation.

A contract is a written specification of the terms, conditions, and actions by several economic agents at various times. A contract sets complete details if the contract provides explicitly for all possible terms and conditions. An incomplete contract can well cover all conditions by implication. In fact, most incomplete contracts cannot mention many life contingencies. Typically, incomplete contracts may not include conditions that would allow both parties to be made better off in the best likelihood of success. After all, incomplete contracts cannot necessarily result in Pareto sub-optimal economic outcomes. Sometimes it is impossible for both parties to foresee the best course of action ex ante under all circumstances.

Both parties make legally enforceable contracts in at least 2 baseline contexts. The first context concerns virtually any kind of financial arrangement. The necessity of contract enforcement is transparent in this context. In most financial arrangements, one party extends credit to another over a period of time, and contract enforcement prevents his or her credit from appropriation (which would otherwise make the core credit arrangements impossible in the first place). Financial contracts that allocate risk would generally be futile without enforcement because one of the parties would not wish to honor the contract terms when the risky outcome becomes known.

In the second context, both parties make enforceable exclusive contracts with the provision of goods or services. No one else can purchase these goods or services on a spot market with a simultaneous exchange for money. Contract enforcement helps avert the hold-up problems, price distortions, and wrong risk incentives. Also, contract enforcement helps prevent the improper breach and underperformance. Sheer costs and information asymmetries may sometimes inadvertently distort this contract enforcement in practice.

The general legal rule of assent indicates that most contracts become legally valid when both parties agree to the substantive terms and conditions in a written form. This rule allows both parties to make enforceable contracts when these economic actors desire so. Also, this rule protects both parties from bearing legal obligations against their wishes. Mutual assent sometimes cannot be simultaneous, but assent contributes to mutually beneficial contract formation. Both the economic and social welfare consequences of disclosure obligations often depend on whether the major information is socially valuable for contract formation and mutual assent. All these disclosure obligations help the buyer and the seller draw clear and valid inferences from silence in the presence of contractual terms and conditions. The prospect of having to pay for harms and damages for breach of contract can often serve as an implicit substitute for more transparent terms and conditions. Both parties further have the opportunity to re-negotiate the contract with new terms and conditions in light of unforeseen circumstances.

When both parties breach the contract, they often have to pay damages as a result. The contractual terms often stipulate in advance the damages. Alternatively, some tribunal determines the damages in a fair and cost-effective manner. The prospect of having to pay damages provides incentives for economic actors to perform their contractual obligations. In accordance with their contractual terms and conditions, both parties can fulfill their own economic goals with proper contract enforcement. An alternative to the use of damages for breach of contract is specific performance. This alternative measure requires some party to satisfy his or her own contractual obligations. Specific performance cannot be the remedy for breach of contract over the provision of goods or services. It may be rather difficult for the courts to enforce contractual terms and conditions in such context due to the problems of monitoring the performance levels of both hard high-skill labor and product quality.

As a general rule, someone who has suffered harms and losses, the plaintiff, can sue when the costs of lawsuit are lower than the economic gains from the lawsuit. The probable economic gains include potential settlements and trial results. When the plaintiff wins the lawsuit, he or she gets compensation for harms and losses. If the plaintiff can afford the litigation costs, he or she chooses to launch the lawsuit. Shavell argues that the private incentive for the plaintiff to sue often misaligns with the socially optimal incentive for him or her to sue. The resultant deviation from the social optimum can be in either direction. On one hand, there can be a substantial divergence between both private and social costs that result in socially excessive litigation. On the other hand, the private and social benefits of litigation often differ dramatically such that a socially inadequate level of litigation emerges from lawsuit deterrence. Specifically, the plaintiff considers his or her private costs and benefits of lawsuit, but not the social costs and benefits of lawsuit. Therefore, the resultant private gains and losses can be larger or smaller than the social costs and benefits. The main implication of this private-social divergence is that state intervention must be desirable. The government can help correct the problems of excessive litigation (by imposing lawsuit taxation or banning litigation in some areas). Alternatively, the government subsidizes civil lawsuits in some other areas. The government has to weigh the ripple effects of lawsuits on injurer behaviors against the broader social costs of lawsuits.

Regardless of whether the legal system creates valuable economic incentives, the private motive for many economic actors to bring lawsuits may be quite large. This tendency can be a fundamental reason for social state intervention. In some other areas, the private incentive for most economic actors to bring lawsuits may be low. For instance, the damages per plaintiff may not be large enough to justify litigation, even though the value of deterrence can be significant. In this latter case, the state should encourage litigation via lawsuit subsidization.

A settlement is a legally enforceable contract and so involves compensation from the defendant to the plaintiff in return for the requirement that the latter agrees not to pursue his claims further. If both parties cannot reach a settlement, we assume that they go to trial. In this alternative case, some tribunal determines the outcome of their lawsuit. In practice, the vast majority of cases eventually settle between the plaintiff and the defendant.

The plaintiff can continue spending on litigation as long as the lawsuit raises his or her probable returns from trial or settlement (net of litigation costs). The defendant can make his or her expenditures as long as the lawsuit helps reduce the probable total outlays. Both parties can continue to spend on litigation in order to rebut each other (until there is some room for mutually beneficial settlement). In practice, the courts often restrict the legal efforts that both parties can undertake in due course. Specifically, the courts can often limit the generic extent of discovery in the form of new evidence, mandatory information disclosure, or expert testimony.

Public enforcement often depends upon the team efforts of public agents such as inspectors, tax auditors, and police officers. When victims of harm naturally acquire knowledge of the identity of injurers, allowing private lawsuits for damages helps motivate victims to sue for justice. In this legitimate way, these victims harness the key information for the main purposes of public enforcement. When victims cannot know the true identity of injurers (or when it is difficult to find injurers), society tends to rely instead on public investigation and prosecution. This public enforcement is true of crimes and of many violations of environmental safety regulations.

If someone commits a harmful act, he or she obtains some gain and also faces the risk of being caught with legal sanctions. The sanctions can be economic fines and prison terms. Fines can be socially cost-effective because they are mere transfers of money, whereas, imprisonment is quite costly due to the expenses of operating prisons for criminal offenders who suffer some significant disutility. In an economic sense, fines are generally preferable to criminal prison terms as a common method of deterrence, since fines are socially cheaper sanctions for the state to impose on criminal offenders (Becker, 1968). So the state should employ fines to the greatest possible extent until the criminal offender runs out his or her wealth before the state imposes imprisonment. Imprisonment should serve as the criminal sanction of the last resort only if the harm turns out to be substantial in the presence of deterrence. Criminal liability depends on a strict assessment of whether the criminal act causes some socially undesirable harm. On the other hand, fault-driven liability can induce many people to behave properly. Fault-driven liability provides a major economic advantage when most people are risk-averse utility maximizers: if most people act responsibly, they cannot be found at fault and hence cannot bear the risk of getting caught with legal sanctions. In a similar vein, fault-driven liability is advantageous when the common form of legal sanctions is imprisonment. In effect, all these legal sanctions deter criminal offenses, induce most people to behave properly, and thus prevent many social costs and prison terms (Shavell, 1987). It is often more difficult for the state to implement fault-driven liability. The practical implementation often requires the state to determine optimal behaviors and fault lines.

Society sometimes reduces harm not only through deterrence but also by imposing legal sanctions to remove people from core positions where these economic actors are able to cause harm. In the legal jargon, these sanctions incapacitate economic actors. Imprisonment is the major incapacitative sanction. There are several other examples. For instance, people can lose their driver licenses due to some violation of traffic rules and regulations. Firms can lose their basic business rights to operate in some domains due to anti-competitive practices. It can be socially desirable for the government to keep someone in jail as long as the resultant reduction in crime from incapacitation exceeds the social costs of imprisonment (Shavell, 1987). It is unlikely for this condition to hold for a long period of time because the proclivity for people to commit crimes often declines dramatically with age.

The subject of criminal law often fits the theory of public law enforcement (Posner, 1985). Imprisonment can serve as the major punishment for criminal acts such as murder, robbery, forgery, and some other felonies etc. With fines alone, deterrence would be grossly inadequate for such criminal offenses. The likelihood of detecting many of these criminal acts is low, and the necessary fines for deterrence is high. However, the total assets of criminal offenders who commit these felonies are often insubstantial. Therefore, the threat of imprisonment is quite essential and important for deterrence. The incapacitative aspect of imprisonment is valuable because of the difficulty of deterring people who are prone to commit criminal acts.

Many of the doctrines of criminal law can help enhance social welfare. Specifically, the proportionality principle is the major criterion of justice in statutory interpretation processes (especially in criminal law) as a logical method of discerning the correct balance between the restrictions on some punishment and the severity of criminal behavior. Within criminal law, the proportionality principle helps convey the notion that the punishment should fit the criminal offense on a case-by-case basis. Fault-driven liability can prove to be socially desirable because this liability system leads to less frequent punishment than strict liability. In criminal law, the focus on intent as a precondition for legal sanctions makes sense with respect to deterrence since people who intend to cause harm are more likely to conceal their criminal acts. In a nutshell, prison terms should serve as commensurate sanctions with respect to socially undesirable criminal acts.

Harvard Law School professor and director Steven Shavell presents his economic analysis of law in terms of the economic properties and consequences of both legal doctrines and institutions. Shavell delves into both the jurisprudence and normative adequacy of the neoclassic economic analysis of law with respect to the costs and benefits of legal rules, procedures, and institutions. Shavell focuses on 5 essential fields of law: property law, liability for accidents, contract law, litigation, and public enforcement and criminal law. This economic analysis of law seeks to identify the ripple effects of legal rules on the behaviors of relevant economic actors. From the normative viewpoint, this standard economic analysis of law further helps assess whether these ripple effects are socially desirable. This economic analysis of law stipulates that most economic actors are rational decision-makers. Thereby, these economic actors maximize their personal lifetime utility in response to legal carrots and sticks (such as economic incentives and criminal sanctions etc).

Shavell further connects the social desirability of legal doctrines and precedents to the first and second fundamental theorems of social welfare. The first fundamental theorem of social welfare states that complete markets lead to the Pareto optimal allocation of economic goods and services with complete information and perfect competition. In this basic sense, no further market exchange would make a person better off without making another worse off. The second fundamental theorem of social welfare states that any Pareto optimum can be a competitive equilibrium for some initial set of endowments. The competitive market exchange can support any socially desirable Pareto optimal outcome. In this new light, some redistribution of initial wealth helps preserve Pareto efficiency in accordance with Bentham (1789) utilitarianism and Becker (1968) and Posner (1972) economic analysis of law and society in the more general sense. However, some specific attempts for the social planner to correct the original distribution of economic resources may inadvertently introduce economic distortions such as public goods, externalities, and information asymmetries etc. In this rare and unique case, complete Pareto optimality may not be attainable with social welfare redistribution.

Shavell focuses on the analytical foundations of 5 major subjects in the economic analysis of law: property, torts, contracts, litigation, and criminal law enforcement (Cooter and Ulen, 2003). Shavell omits some specific areas of law and economics such as antitrust law, taxation, and corporate law. Economic incentives and carrots and sticks tend to differ dramatically between the 5 major subjects and most other areas of law and economics.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

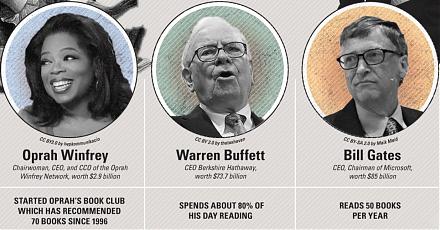

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2023-09-14 09:28:00 Thursday ET

Colin Camerer, George Loewenstein, and Matthew Rabin assess the recent advances in the behavioral economic science. Colin Camerer, George Loewenstei

2024-02-04 08:28:00 Sunday ET

Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms most stock market indexes from 2017 to 2024. Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms the ma

2019-01-02 06:28:00 Wednesday ET

New York Fed CEO John Williams listens to sharp share price declines as part of the data-dependent interest rate policy. The Federal Reserve can respond to

2019-07-15 16:37:00 Monday ET

President of US-China Business Council Craig Allen states that a trade deal should be within reach if Trump and Xi show courage at G20. A landmark trade agr

2019-07-27 17:37:00 Saturday ET

Capital gravitates toward key profitable mutual funds until the marginal asset return equilibrates near the core stock market benchmark. As Stanford finance

2017-10-03 18:39:00 Tuesday ET

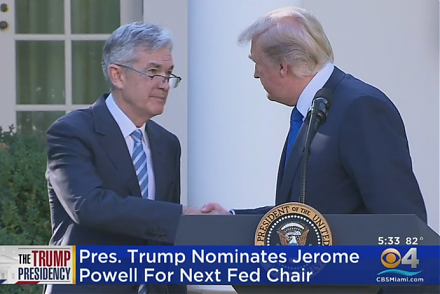

President Trump has nominated Jerome Powell to run the Federal Reserve once Fed Chair Janet Yellen's current term expires in February 2018. Trump's