2023-02-21 08:27:00 Tue ET

stock market technology data antitrust global macro outlook competition bilateral trade free trade fair trade trade agreement trade surplus trade deficit multilateralism neoliberalism world trade organization regulation public utility compliance economic growth capital global financial cycle gdp output

Mark Granovetter (2017)

Society and economy: frameworks and principles

In his book on Society and Economy, Mark Granovetter delves into the intellectual origins of the global economy in a vital way that transcends disciplinary boundaries. Granovetter confines his attention to typical economic examples in the usual sense of pertaining to the production, distribution, or consumption of goods and services. This analytic approach represents the hardcore of economic activity and therefore departs substantially from the parallel goal of sociological imperialism.

Granovetter first focuses on the core economic activity, i.e. production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. This insistence on core economic activity can be viewed as a fundamental way for Granovetter to demonstrate the relevance of social relations in the pure business context. Social relations reshape economic trends, structural changes, and team interactions for better output and employment. The second basic principle relates to an insistence on the importance of intellectual holism. Granovetter differentiates his socioeconomic analysis from the traditional economic focus on costs and benefits. Also, Granovetter argues against the basic strategy of relying on a single simple explanation, model, or paradigm for economic phenomena. In this light, Granovetter indicates that our notion of model parsimony depends on null hypothesis development. The null hypothesis sometimes dictates and determines the level of analysis that we favor over time. Granovetter supports an intermediate position that economic choices often tend to arise from the broader context of social relations that most global citizens embed in the central fabric of modern democratic state rule of law. In the grand pursuit of self-interest and even self-realization, economic agents choose to trade off economic costs and benefits to live out the highest and truest expression of mankind. Most people strive to fulfill their own life purposes and legacies to help enrich the economic lives of others. In these social roles, economic agents consider their optimal choices of intertemporal substitution to spare their current consumption in return for better future economic growth, development, and capital investment accumulation. In this longer-run view, social relations shape economic trends, structural changes, and team interactions in the broader business context.

As a prolific economic sociologist, Mark Granovetter has published a pair of articles, Strength of Weak Ties (1973) and Social Structure and Economic Action (1985), in the American Journal of Sociology. These twin publications each have 30,000+ citations on Google Scholar. These economic citations compare favorably with The Market for Lemons by Nobel Laureate George Akerlof (1970) in Quarterly Journal of Economics.

How should the basic role of socialization adjust as people move across empirical contexts? In some specific contexts, the traditional economic analysis of both costs and benefits with its focus on self-interest may be okay. In other contexts, however, it would be reasonable to assess the gradual evolution of social relations when we study longer-term trends and empirical facts. From time to time, structural changes in social relations can often cause abrupt changes in tastes, preferences, and even technological advances. Most economic growth models such as Solow-Swan tend to view these longer-term technological advances as exogenous sources of macro economic momentum. From inclusive institutions to adaptive rules and regulations, better social infrastructure helps embed long prevalent social relations into several economic considerations of costs, benefits, and their trade-offs.

Recent empirical evidence delves into the robust relation between colonialism and subsequent social infrastructure. In the institutional view, geographical differences between subtropical and temperate regions at the time of colonization have caused Europeans to colonize with either extractive or inclusive institutions. Such different strategies of colonization affect subsequent institutional development and thereby economic growth. The chosen establishment of inclusive or extractive institutions serves as a major pivotal source of international differences in social infrastructure as well as economic growth nowadays. The geographic diseases environment can dictate the chosen colonial strategy. In particular, Europeans face extremely high mortality risks in tropical regions (especially from malaria and yellow fever), but the average death rates are substantially lower in temperate regions. In the subtropical high-disease environments, European colonizers establish highly extractive states or even authoritarian institutions in order to exploit natural resources from colonies with little settlement and private property protection. In the temperate low-disease environments, European colonizers choose to establish inclusive states or settler colonies with better socioeconomic development and democratic rule of law. This empirical fact prevails in the economic comparison of North America versus South America.

Granovetter moves onto the crucial role of mental constructs (such as social norms, values, and beliefs) and then discusses trust and power. Social networks matter in light of the fact that socioeconomic goals can involve known others as a significant element. This argument that social networks of known others often matter a lot has come to be identified as the social embeddedness perspective.

Granovetter discusses at least 3 dimensions of social networks that he defines as dyadic, structural, and temporal embeddedness. Dyadic influences often relate to pairwise social relations between economic actors. Immediate social relations and connections can cause behavioral changes over time. Structural influences locate economic agents within the overall social network of connections. Temporal effects reflect ongoing social relations as the vast majority of economic agents do not start fresh each day (but carry the baggage of previous social interactions from time to time). Built into basic cognitive equipment is a remarkable capacity to file away the emotional details and reflections of past social relations for long periods of time. In this particular context, temporal effects often refer to the path dependence of prior social relations. This path dependence extends its purview to the global history of social networks.

Dense linkages and connections often help facilitate the sustenance of both social norms and values via joint agreement, common sense, and the path dependence of enforceable economic sanctions. Social networks help mediate between micro and macro levels. Granovetter further develops some of the fundamental ways that social networks relate to broader themes such as trust, power, norms, values, and beliefs etc. These broader themes contribute to the social fabric of most institutions in modern democratic societies and economies. Social roles, norms, values, and even expectations often help shape human behaviors (Akerlof and Kranton, 2000). In addition to human responses to socioeconomic incentives, altruistic motives can explain some specific behaviors over time.

Across many modern cultures, people seek the non-economic goals of sociability, approval, status, and power. These goals are available only in a social context via the social networks of others. Given the importance of social motives, it is common for economic relations that begin in a neutral impersonal way to develop social and non-economic content as people try to combine both social relations and economic trade-offs to help enrich the lives of others.

In the broader socioeconomic context, many people seek approval and admiration. Insincere approval is better than none but pales in comparison to approval without ulterior motive. In the normal course of social relations, economic actors often have to strike a better balance between instrumental values and consummatory norms. For example, people often go to a party to enjoy a good time for social connections; yet, information about jobs (or other economic costs and benefits) can pass among party goers.

In an economic view, people often tend to conform to social norms, values, beliefs, and expectations etc because these economic actors think the incentives, benefits, and rewards outweigh the costs. However, Granovetter feels that this instrumental view is inadequate. In many everyday contexts, people conform to social norms in spite of the immediate costs and benefits in accordance with societal expectations. Many people would probably assent to the proposition that self-interest represents the cement of society, until these economic agents reflect on the social implications. In reality, human emotions such as guilt and shame often help sustain social norms. Some social situations elicit strong emotional responses and so specific behaviors in light of key social relations. At the macro level, the social psychology of emotions serves as an important part of the fuller explanation for social norms, values, and beliefs. The relative strength of emotional responses depends on the social context in terms of the potential and actual reactions of others who observe what we have done. Significant others such as family members, neighbors, or coworkers would often constitute the social reference group. In the current neighborhood of contacts, many people leverage their social relations to make wiser economic trade-offs and decisions over time.

How do social norms from small close-knit communities scale up to the macro level of modern society? Granovetter suggests that social networks probably play a vital role by connecting small communities into the substantially larger reference group. Better social infrastructure often helps enhance economic growth and productivity through high education, skill transformation, and other human capital accumulation over time. In the specific context of economic development, Munshi (2014) shines fresh light on the important role of both caste and community networks in shaping economic events such as capital investment, school selection, and immigration.

Social norms of both fairness and trust help shape the path of corporate ownership and governance structures in time (Blair and Stout, 2001). In corporate governance, the rules of the game often depend on what most economic agents perceive to be fair. Stakeholders regard some distribution of corporate wealth and power as unfair if this distribution departs substantially from the terms of a reference transaction, which is the transaction that defines the benchmark for corporate interactions (Jolls, Sunstein, and Thaler, 1998). Due to cultural differences, the reference transaction varies from country to country. For instance, American culture often tends to resist central authority and hierarchy more than French culture (Bebchuk and Roe, 1999). Codetermination reflects the need for a fair go for key employees in Germany (Roe, 1993). Political connections matter a great deal to Chinese CEOs in several major corporate decisions, whereas, these connections generally have a negative effect on corporate performance in terms of post-IPO net profit growth or revenue growth (Fan, Wong, and Zhang, 2007). In East Asia, some large corporations often find it necessary to bribe senior bureaucrats to seek economic rent protection in the form of exclusive trade rights, commercial privileges, and even preferential government contracts (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000). Moreover, East Asian and Italian large corporations often view family involvement as an indispensable value driver (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000; Licht, 2001). All these social norms help set the social reference transactions or rules of the game. As a result, such social rules can help create certainty for better stakeholder interactions.

Firm-specific fairness norms help enhance the corporation’s efficiency due to more cooperation and less opportunism among its stakeholders (Cooter and Eisenberg, 2000). The gradual internalization of fairness norms incentivizes stakeholders to trust one another in the main nexus of firm-specific capital investments. How willing stakeholders are to trust others often shapes the initial ownership and governance arrangements in the corporate context (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1997). However, trust alone often cannot facilitate functional convergence toward the key Berle-Means image of the modern corporation with stock ownership dispersion. Because there can be substantial heterogeneity in social norms of both trust and power, what economic actors regard as fair in Japan may not be equally fair in Australia and New Zealand. In a similar vein, German codetermination may not be a suitable solution to the agency problem that U.S. companies face. To the extent that social norms of both trust and power differ from country to country, this divergence suggests that corporate ownership and governance schemes continue to differ over time. This persistent divergence sometimes reflects global differences in social norms and fair reference transactions.

Economic actors and agents often need to appreciate social norms and institutions in the broader business context of both social relations and team interactions. Key social institutions refer to rather long prevalent features of economic lives of others that often help coordinate group behaviors in conventional economic events. In the institutional view of economic organizations, early technology adopters are careful about the efficiency aspects of new technological advances. Once these new tech advances (such as iPhones and iPads) become acceptable in the consensus view, widespread adoption begins to depart from economic consequences. Subsequent ubiquitous adoption arises from a pervasive sense that new technological practices somehow tend to be more legitimate. Granovetter advocates the institutional logic that both professional practitioners and consultants help spread the long prevalent use of new technological advances. These social institutions adopt new modes of technological practices on the basis of legitimacy of dominant economic structures (rather than what people regard as efficient in terms of their explicit consideration). In the example of iPhones and iPads, many users now consider their continual use and ownership of the smart mobile devices fresh social signals of status, trust, and power etc. Granovetter next turns to the stark comparison of Silicon Valley versus Route 128 in Massachusetts.

In Silicon Valley, small nimble lean enterprises permeate firm-specific boundaries. The lean startup mentality runs through many tech titans such as Apple, Facebook, Google, Hewlett-Packard, Twitter, Tesla, and so on. Numerous lean startup teams differ substantially from the relatively autarkic large corporations on Route 128. In this view of social institutions, Granovetter suggests that regional cultures arise out of team efforts that many economic actors coordinate to use different structural or normative patterns to solve specific problems in new technological advances and economic organizations.

As Granovetter indicates in his unique view of social norms and institutions, most economic actors and agents compare several different institutional approaches. At the same time, these economic actors and agents can transpose one institutional form from one domain to another. Such economic decision-makers mix and match and combine both social and economic elements from a wide variety of institutional approaches.

Granovetter reconsiders the hypothetical example of a Wall Street senior manager who serves as a smart and diligent financial analyst. This senior manager also has a suburban spouse and children, so there are social pressures on him to reallocate his time away from lower Manhattan to the family sphere. Granovetter analyzes an inherent social role conflict in this case. This conflict thereby draws attention to the intersection of double domains that make institutional demands on this Wall Street senior manager: economic work demands on the one hand and social norms and values for the family on the other hand. This basic example brings out an important overlap between social roles and institutions. The most important social norms and values often specify proper behaviors and responsibilities for its various social role incumbents: consumers, workers, and directors in the economy; parents, spouses, and kids in the family; and citizens and bureaucrats in the polity.

A practical example pertains to the South Korean social institutions of both family and kinship. The economic rise of Samsung, Hyundai, Kia, and LG etc reflects the social influence of primogeniture (the oldest son inherits all family business wealth in the gradual emergence of the chaebol). South Korean business men transpose social relations from the familial domain to the economic sphere of both business organizations and disruptive technological advances. In a fundamental fashion, the combination of social and economic interactions helps transform the South Korean economy in recent decades.

Mark Granovetter analyzes the intellectual origins of the global economy in a vital way that transcends disciplinary boundaries. Granovetter confines his attention to key economic examples in the usual sense of relating to the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. This main approach reveals the hardcore of economic interactions and therefore departs substantially from the parallel goal of sociological imperialism.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2019-06-30 12:37:00 Sunday ET

AYA Analytica finbuzz podcast channel on YouTube June 2019 In this podcast, we discuss several topical issues as of June 2019: (1) Federal Reserve h

2019-01-09 07:33:00 Wednesday ET

Apple revises down its global sales revenue estimate to $83 billion due to subpar smartphone sales in China. Apple CEO Tim Cook points out the fact that he

2017-10-03 18:39:00 Tuesday ET

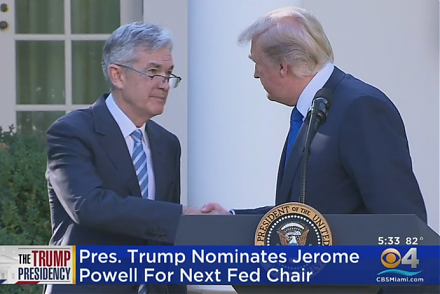

President Trump has nominated Jerome Powell to run the Federal Reserve once Fed Chair Janet Yellen's current term expires in February 2018. Trump's

2020-05-14 12:35:00 Thursday ET

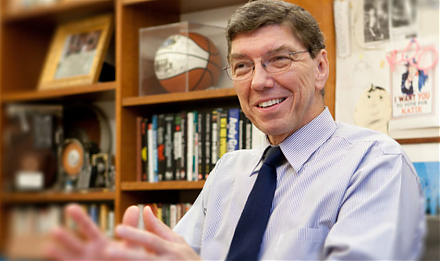

Disruptive innovators can better compete against luck by figuring out why customers hire products and services to accomplish jobs. Clayton Christensen, T

2018-06-10 19:41:00 Sunday ET

Apple enters a multi-year content partnership with Oprah Winfrey to provide new original online video and TV programs in direct competition with Netflix, Am

2019-11-19 09:33:00 Tuesday ET

American unemployment declines to the 50-year historical low level of 3.5% with moderate job growth. Despite a sharp slowdown in U.S. services and utilities