2022-05-05 09:34:00 Thu ET

corporate finance fama and french graham and harvey baker and wurgler agency theory corporate payout cash payout dividends share repurchases financial constraints financial lifecycle lower propensity to disgorge cash

This corporate payout literature review rests on the recent survey article by Farre-Mensa, Michaely, and Schmalz (2014). Out of the conventional motives of why the typical firm makes cash payout in the form of both dividends and repurchases (cf. the agency, signaling, and tax stories), the cross-sectional evidence is most persuasive in favor of agency considerations. Some recent studies of the May 2003 dividend tax cut confirm that differences in the separate taxation of dividends and capital gains have at best a second-order impact on setting corporate cash payout. None of the conventional payout explanations can account for the secular changes in how corporate payout materializes over the past few decades. During this time, share repurchases have replaced dividends as the primary vehicle for corporate payout (Fama and French, 2001; DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner, 2004; Skinner, 2008). More recent theoretical and empirical developments of corporate payout literature focus on cash distributions of regular and smooth dividends and market-timing repurchases as an integral part of the firm’s larger financial ecosystem with important implications for corporate investment, capital structure, cash management, risk management, managerial rent protection, and corporate ownership and governance (e.g. Lambrecht and Myers (2012, 2015)).

Farre-Mensa, Michaely, and Schmalz (2014) summarize several primary empirical facts about corporate cash distributions. Corporate cash distributions entail substantial dollar amounts that reflect large wealth transfers in the economy. For instance, U.S. public firms pay $800+ billion in dividends and repurchases. For better exposition, the bullet points below sum up these empirical facts:

Fama and French (2001) empirically find that the fraction of public firms that pay out cash dividends has decreased substantially from 66.5% in 1978 to 20.8% in 1999. Part of this decline is due to a structural shift in the population of public firms toward small firms with low profitability and robust asset growth. This structural shift arises from an explosion of new lists from 3,638 in 1978 to 5,670 in 1997. The low profitability of these new lists explains at least part of the decline in the fraction of public dividend payers.

Furthermore, Fama and French (2001) run logit regressions to gauge the propensity for the typical firm to pay out cash dividends. After the econometrician controls for a unique set of firm characteristics such as profitability, asset growth, market-to-book, and size, the typical firm’s much lower propensity to pay out dividends explains half of the drastic decline in the fraction of public dividend payers. Specifically, the typical firm’s propensity to pay cash dividends declines by about 25% while the actual decline in the fraction of public dividend payers is nearly 50%. In essence, this lower propensity to pay out dividends is as important as the structural shift in firm composition in explaining the decrease in the proportion of public dividend payers.

Grullon and Michaely (2002) and DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner (2004) empirically report that the decline in the number of public dividend payers suggests an increase in the overall dividend concentration with a 22.7% increase in the real dollar amount of dividend payout by industrial firms from 1978 to 2000. Also, Grullon and Michaely (2002) propose the substitution hypothesis that many public firms nowadays successfully substitute cash dividends with share repurchases as the dominant form of corporate payout. DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner (2004) wisely observe that the large reduction in the number of public dividend payers occurs almost entirely among firms that pay relatively small dividends while there is a simultaneous substantial increase in cash dividend payout by the largest dividend payers. As a result, the increase in real dividend payout by large and more profitable firms at the top of the dividend distribution swamps by a broad margin the reduction in real dividend payout by small and unprofitable firms at the bottom of the dividend distribution. During the same time period, the aggregate increase in net income significantly outpaces the increase in real dividend payout and thus results in a systemic decline in both the dividend payout ratio and the dividend yield (Grullon and Michaely, 2002).

DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner (2004) find that NYSE firms pay the majority of industrial dividends. This empirical fact suggests the tendency for older and more stable firms that pay regular dividends to list their shares on NYSE. In contrast, young and risky firms that are less likely to pay regular dividends list their shares on AMEX and NASDAQ. Dividend concentration can arise from the recent concentration of corporate income supply (Linter, 1956; DeAngelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner, 2004). The top 25 dividend payers distribute more than 55% of the aggregate cash dividends. It is noteworthy that 14 of these top 25 dividend-payers are large, stable, and mature Dow Jones industrial firms. However, the vast majority of dividend non-payers are high-tech growth firms with high future income potential. In essence, DeAgnelo, DeAngelo, and Skinner’s (2004) empirical results help demystify the puzzle of *dividend disappearance* from Fama and French’s (2001) landmark study.

Skinner (2008) empirically finds that changes in the corporate income cross-section help explain changes in both dividend payout and share buyback from 1980 to 2005. Moreover, share repurchases increasingly substitute for dividends (both for dividend payers and sole share repurchasers). A special group of firms comprises profitable firms that pay both smooth annual dividends and regular repurchases. These firms dominate the distribution of both corporate net income and dividend payout, with well over half of these aggregates in the recent years. These firms commit to their regular dividend distributions mainly due to an implicit obligation to continue this dividend smoothing practice (Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely, 2005). While these profitable firms use both cash payout mechanisms, these firms increasingly substitute share repurchases for dividends. Over the biennial window, corporate income helps explain the variation in the level of stock buyback, and corporate managers time repurchases over this period (Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely, 2005; Peyer and Vermaelen, 2009). Share repurchases are flexible enough to boost earnings per share (EPS) (Bens, Nagar, Skinner, and Wong, 2003) or to distribute cash for the avoidance of potential agency conflicts (Jensen, 1986; Harford, Humphery-Jenner, and Powell, 2012).

Over the period from 1980 to 2005, firms that only pay dividends have declined from 13% to 7% of the number of firms and from 8% to 2% of all dividend and repurchase distributions. This evidence further supports the secular trend that repurchases substitute for dividends. Overall, Skinner’s (2008) empirical results accord with the substitution hypothesis that share repurchases have become the dominant form of corporate payout in comparison to cash dividends. The use of share repurchases as the dominant payout mechanism at least partly helps demystify the EPS dilution puzzle.

Biennial Lintner (1956) regressions of changes in dividend or total payout on both corporate income and past dividend or total payout suggest a structural shift in the empirical relation between corporate income and cash payout. Over the subperiods 1980-1994 to 1995-2005, the dividend mean-reversion is slow and steady at a rate less than –25% while the total payout mean-reversion has significantly increased in speed from –31% to –71%. While the typical firm pays a cash dividend of 9 cents per dollar of corporate income in 1980-1994 and a cash dividend of 17 cents per dollar of corporate income in 1995-2005 (p-value>0.27), the typical firm’s total payout increases from 26 cents per dollar of corporate income in 1980-1994 to 56 cents per dollar of corporate income in 1995-2005 (p-value<0.01). In this light, Skinner (2008) attributes this significant difference to the discretionary use of share repurchases. Total payout more closely tracks corporate income over time since the typical firm increasingly uses stock buyback to absorb the variation in corporate income. In sum, dividend payments increase smoothly over time and are largely independent of the variation in corporate income while share repurchases increasingly absorb this variation.

Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen (1995) examine the long-term firm performance after the major announcements of open market repurchases. The average abnormal 4-year post-announcement buy-and-hold return is 12%. For value stocks, the average abnormal return is 45.3% because these companies are more likely to repurchase due to temporary stock market undervaluation. For glamour stocks, the average abnormal return is insignificant because these companies are less likely to repurchase due to temporary stock market undervaluation. At least with respect to value stocks, the market errs in its initial response and appears to ignore much of the information content of share repurchase announcements.

Ikenberry, Laknoishok, and Vermaelen (1995) also examine the short-term cumulative abnormal return performance both before and around the major announcements of share repurchases. While the average abnormal return is significantly negative at –2.86% to –3.59% from 20 days to 3 days prior to the share repurchase announcement date, the average abnormal return is significantly positive at 2.33% to 4.25% in the 5 days around the repurchase announcement date. It is important to note Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen’s (1995) approach to matching sample firms with benchmark firms. The econometrician first sorts individual stocks into size deciles and book-to-market pentiles with NYSE breakpoints. Then the econometrician calculates the mean equally weighted portfolio returns for the respective size deciles or 50 size-book-to-market subgroups. The abnormal return is thus the wedge between each sample firm’s stock return and the stock return on the corresponding size and size-book-to-market portfolio (Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen, 1995; Nohel and Tarhan, 1998). While this method seems reasonable, some recent studies use the alternative approaches proposed by Lee (1997) and Chan, Ikenberry, and Lee (2004) who suggest the use of at least 5 control firms with the closest book-to-market ratio to avoid noisy point estimates (Barber and Lyon, 1996; Lyon, Barber, and Tsai, 1999) (cf. Chen and Wang (2012: 315)).

Grullon and Michaely (2004) empirically assess the information content of share repurchases. Contrary to the implications of many corporate payout theories, Grullon and Michaely (2004) find that repurchase announcements do not precede an improvement in operating performance. However, share repurchasers experience a significant reduction in both systematic risk and cost of capital relative to non-repurchasers. In accordance with the free cash flow hypothesis (Jensen, 1986; Stulz, 1990; Nohel and Tarhan, 1998), Grullon and Michaely (2004) report that the stock market reaction to repurchase announcements is more positive among those firms that have a higher propensity to overinvest to the detriment of shareholders. While stock analysts tend to revise downward their expectations of operating performance metrics such as return on assets, return on cash-adjusted assets, return on sales, and cash-flow return on assets, many investors underreact to share repurchase announcements because these investors initially underestimate the decline in the cost of capital. In essence, the evidence contradicts the repurchase signaling hypothesis in favor of the free cash flow hypothesis (Nohel and Tarhan, 1998; Grullon and Michaely, 2004).

Peyer and Vermaelen (2009) empirically reject the hypothesis that the buyback anomalies due to market overreaction to bad news or temporary market undervaluation have disappeared over time (Lakonishok and Vermaelen, 1990; Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen, 1995). Open market repurchases are a key response to stock market overreaction to bad news such as significant analyst downgrades and pessimistic long-term earnings forecasts. Firms that experience the most negative market overreaction to bad news before the buyback announcement date enjoy the largest long-run abnormal returns post-announcement. A typical small firm with a low market-to-book ratio, a low prior return, and an indication of motivation for the buyback because of market undervaluation or best use of money is most likely to be undervalued relative to the peer firms.

Chen and Wang (2012) empirically investigate how the financial constraints of share repurchasers affect their post-buyback performance. This empirical study contrasts the prior research that sheds light on the significantly positive effect of share repurchases on subsequent stock return performance. For instance, Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen (1995) document positive long-run abnormal returns up to 4 years after major share repurchase announcements. Grullon and Michaely (2004) demonstrate that stock prices impound lower costs of capital only gradually while these post-buyback changes in systematic risk serve as a plausible explanation for the long-run upward stock price trend. Gong, Louis, and Sun (2008) suggest that deliberate earnings deflation around repurchase announcements is another key reason for the benign post-buyback abnormal stock returns for share repurchasers. Peyer and Vermaelen (2009) report strong empirical support for the long-term abnormal returns as a correction of market overreaction to bad news prior to major share repurchase announcements.

Even though these previous studies suggest that open market share repurchases enhance firm value, share repurchasers may suffer lower corporate liquidity after stock buyback. Specifically, lower cash balances and higher leverage after share buyback lead to a decline in corporate liquidity for share repurchasers. If share repurchasers are financially constrained before share buyback, lower corporate liquidity that arises from share repurchases can be pernicious. As it becomes difficult to finance future investment projects, such firms may be less competitive due to their underinvestment in the product market (Froot, Scharfstein, and Stein, 1993; Chevalier and Scharfstein, 1996; Campello, 2003; Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach, 2004). With less cash, these firms are more likely to suffer financial distress risk (Opler, Pinkowitz, Stulz, and Williamson, 1999; Kaplan and Zingales, 2000; Lamont, Polk, and Saa-Requejo, 2001; Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach, 2004; Whited and Wu, 2006; Denis and Sibilkov, 2010). Unlike financially un-constrained repurchasers, financially constrained repurchasers overall are likely to exhibit subpar post-buyback performance due to a decline in their corporate liquidity.

Chen and Wang (2012) use a set of metrics to examine how the financial constraints of share repurchasers affect firm performance after major repurchase announcements. The first metric is the Kaplan-Zingales (1997) index (Lamont, Polk, and Saa-Requejo, 2001; Baker, Stein, and Wurgler, 2003; Chen, Goldstein, and Jiang, 2007; Hennessy, Levy, and Whited, 2007). This metric gauges the wedge between the internal and external costs of finance. Financially constrained firms or equity-dependent firms should have higher Kaplan-Zingales indices and tend to face higher costs for financing their operational needs with external capital. To complement the use of the Kaplan-Zingales (1997) measure, Chen and Wang (2012) consider the cash flow sensitivity of cash (Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach, 2004), the Whited-Wu (2006) finan-cial constraints risk measure, and the cash flow sensitivity of capital investment (Fazzari, Hubbard, and Petersen, 1988). With 4,700+ share repurchase announcements from 1990 to 2007, Chen and Wang (2012) report that financially constrained firms repurchase shares under each metric of financial constraints risk. These firms display significant declines in cash and cash flow and significant increases in leverage after share repurchase announcements. Such changes result in substantial declines in corporate investment for these financially constrained firms.

Both initial and long-term stock price reactions to share repurchase announcements are significantly less favorable for financially constrained firms than for financially unconstrained firms. The 3-day abnormal returns for financially constrained firms range from 0.23% to 0.75% in contrast to 0.92% to 1.83% for financially unconstrained firms. Up to 4 years after the share repurchase announcement date, financially constrained firms experience average buy-and-hold abnormal returns of –5.96% to –1.40% per year in comparison to 1.12% to 1.52% per year for financially unconstrained firms. In essence, share repurchases yield subpar post-buyback stock return performance for those firms that face severe financial constraints.

Using the Altman (1968) Z-score to gauge distress risk, Chen and Wang (2012) find that after repurchase announcements financially constrained firms experience a significantly greater increase in distress risk than financially unconstrained firms. There is also a significantly higher increase in the fraction of firms with high default probabilities in the post-buyback period for financially constrained firms. These results indicate that financially constrained firms are more likely to suffer financial distress risk after the share repurchase announcement date.

Chen and Wang (2012) further find that top managers of financially constrained firms tend to hold more in-the-money stock options than top managers of financially unconstrained firms. These overconfident managers often overestimate the future returns on share repurchases and thus postpone their exercise of in-the-money stock options (Malmendier and Tate, 2005, 2008; Ben-David, Graham, and Harvey, 2007). Chen and Wang (2012) find that financially constrained firms with more overconfident managers appear to experience unfavorable post-buyback stock return performance. For this reason, Chen and Wang (2012) suggest that managerial hubris can help explain why financially constrained firms buy back shares even if their share repurchases do not improve shareholder wealth.

Open market share repurchases often correlate with stock undervaluation, but this signal about firm value sometimes misleads investors. Babenko, Tserlukevich, and Vedrashko (2012) conjecture that corporate executives who buy their firm’s shares prior to a major repurchase announcement add credibility to the signal about equity undervaluation. In accordance with this intuitive conjecture, Babenko, Tserlukevich, and Vedrashko (2012) empirically find that abnormal returns around share repurchase announcements positively correlate with past insider purchases. This result is more pronounced for firms that experience less efficient price discovery. In essence, insider purchases help predict post-announcement stock returns.

Bliss, Cheng, and Denis (2015) report significant reductions in both dividend payout and share buyback during the 2008-2009 financial crisis. Repurchase reductions prevail to a larger extent than dividend cuts. Payout reductions are more likely in firms with higher leverage, more valuable growth options, and lower cash balances (i.e. these firms are more susceptible to the negative consequences of an external financing shock). Firms appear to use the proceeds from payout reductions to maintain cash reservoirs for financing future firm investment opportunities. In this light, an external shock to the supply of credit (net of demand effects) during the financial crisis increases the marginal benefit of cash retention. Payout reductions in general, and repurchase reductions in particular, serve as a substitute form of corporate finance.

During the 2008-2009 financial crisis, the percentage of firms that either reduce or eliminate dividends increases from 6% in 2006 to 25% in 2009 while the percentage of firms that curb repurchases increases from 52% in 2006 to 89% in 2009. In contrast to cash dividends, share repurchases can be viewed as a flexible form of corporate payout. Bliss, Cheng, and Denis’s (2015) logit regressions of the indicator for payout reductions as well as panel regressions of payout reductions shed light on the evidence of payout reductions as a substitute form of corporate finance. This result echoes some recent studies of corporate cash and payout decisions (Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely, 2005; Campello, Graham, and Harvey, 2010; Leary and Michaely, 2011; Almeida, Campello, and Weisbach, 2004; Faulkender and Wang, 2006; Bates, Kahle, and Stulz, 2009; Harford, Mansi, and Maxwell, 2014; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 2000; Dittmar and Mahrt-Smitth, 2007; Harford, Mansi, and Maxwell, 2008):

Grullon and Michaely (2002) demonstrate the share repurchases have become not only an important form of corporate payout but also a reasonable substitute for dividend payout. Specifically, the internal finance that firms use to fund their share repurchases would otherwise have been used to increase dividend payout. Young firms have a higher propensity to pay cash through share repurchases. Further, share repurchases have become the preferential form of cash payout initiation. Although large and profitable firms appear to maintain their regular and smooth dividend payments, these firms exhibit a higher propensity to pay out cash through share buyback. These results indicate that firms have gradually substituted repurchases for dividends. The substitution hypothesis serves as a plausible alternative explanation for share buyback other than temporary market undervaluation.

Bens, Nagar, Skinner, and Wong (2003) empirically find that corporate managers steer share repurchase decisions to contain the effect of earnings per share (EPS) dilution. Corporate managers tend to increase the level of their firm’s share buyback when the dilutive effect of employee stock options (ESOs) on EPS increases. This behavioral pattern is more pronounced when EPS growth falls short of the target rate. In this light, the potential EPS dilution that arises from the collective exercise of ESOs strengthens the usual interpretation of corporate earnings management. This behavioral phenomenon serves as an additional reason for share buyback other than temporary market undervaluation.

Massa, Rehman, and Vermaelen (2007) empirically study the tendency of firms to mimic the repurchase announcements of their industry peers. Through share buyback, a firm sends a positive signal about its own financial capacity and a negative signal about the financial capacity of its competitors. These signals induce the industry peers to closely mimic the firm’s share repurchase decisions. In highly concentrated industries, a firm’s share repurchase announcement lowers the stock prices of the other peers in the same industry. In this light, share repurchases serve as a strategic reaction to the repurchase decisions of other firms in the same industry rather than an attempt to time the stock market due to temporary stock market undervaluation. In more concentrated industries, share repurchasers experience a lower increase in firm value in comparison to their counterparts in less concentrated industries in the post-announcement period. This micmicking hypothesis is another alternative explanation for share buyback other than temporary stock market undervaluation.

Becker, Ivkovic, and Weisbenner (2011) empirically examine demographic variation to assess the effect of local dividend clienteles on corporate payout. Most retail investors prefer local stocks while most older investors prefer dividend-paying stocks. Firms that are headquartered in areas where seniors constitute a large fraction of the population are more likely to pay dividends with more dividend initiations and higher dividend yields. Specifically, a one-standard-deviation increase in the fraction of senior population raises the likelihood of dividend initiation by 50% of the baseline effect. This marginal effect is equivalent to the marginal effect of a one-standard-deviation increase in the firm’s market capitalization or an increase in the number of years since the firm’s IPO from 6-10 years to 16-20 years. Determinants of the dividend initiation decision are particularly relevant because the typical firm initiates dividend payout to commit to a long stream of cash outlays (in contrast to a simple one-off repurchase commitment that can be easily reversed later) (Linter, 1956; Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely, 2005). Several psychological reasons help explain the empirical nexus between local demographic dividend demand and subsequent dividend initiation. For instance, Thaler and Shefrin (1981) point to self-control and regret avoidance motivations for investors to consume cash dividends to avoid the temptation to liquidate shares. Further, Shefrin and Statman (1984) stress the mental accounting hypothesis that investors tend to place dividends and capital gains in different mental accounts for different precautionary and speculative motives. In addition to this mental accounting hypothesis, Scholz (1992) suggests a tax clientele rationale. Because senior investors are inclined to cash out dividends for near-term personal consumption, these investors attend to the above root causes of both psychological motivation and differential taxation.

Michaely and Roberts (2011) empirically find that private firms smooth dividends significantly less than their public counterparts. The scrutiny of public capital markets plays an important role in explaining the propensity of firms to smooth dividends over time. Also, public firms pay higher dividends that tend to be more sensitive to changes in corporate investment opportunities than otherwise similar private firms. Private firms with greater stock ownership dispersion pay lower dividends than public firms with similar characteristics. Furthermore, firms that have transitioned from private firms to public firms increase their dividend payouts during the transition time. Michaely and Roberts (2011) carry out panel regressions in the form of the canonical dynamic dividend model by Lintner (1956), Fama and Babiak (1968), and Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely (2005).

Michaely and Roberts (2011) find that the target payout ratio is 15% to 23% of total corporate income while the speed of dividend adjustment lands in the broad range of 0.83, 0.63, and 0.41 for wholly owned private firms, private firms with high stock ownership dispersion, and public firms. While private firms with high stock ownership dispersion pay lower dividends than public firms with similar characteristics, firms that have transitioned from private firms to public firms increase their dividend payments around the transition time. Furthermore, public firms are more reluctant to cut dividends than private firms. The scrutiny of capital markets induces public corporations to smooth their dividends much more than private firms regardless of their stock ownership structures.

Dittmar and Field (2015) find that corporate incumbents do time the market by repurchasing shares when the stock price is lower than the average price. Less frequent share repurchasers and firms that experience lower prior stock returns buy back shares at low market prices. After the econometrician controls for the Fama-French (1993) risk factors, repurchasers earn positive returns up to 36 months after the actual share buyback. This empirical pattern is more pronounced for infrequent repurchasers that appear to better time the market. Firms pay lower relative repurchase prices after a prolonged period of low abnormal returns (Peyer and Vermaelen, 2009). Dittmar and Field (2015) use analyst coverage and EPS forecast dispersion as proxies for information asymmetries in the relative repurchase price regressions. Smaller firms, firms with lower market-to-book, and firms with dramatic and volatile prior stock price run-down, often attain lower relative repurchase prices. As a result, firms with substantial stock market undervaluation are more likely to time the stock market through share buyback.

Lambrecht and Myers (2012) demonstrate how managerial rent protection can yield regular and smooth dividend payout. In their theoretical model, shareholders demand regular and smooth dividend payout to limit agency costs, but the costs of joint shareholder coordination allow corporate insiders to extract rent. Risk aversion and habit formation are present in the utility function for these corporate managers who desire regular and smooth economic rent that in turn requires regular and smooth dividend payout. While the level of dividend payout can increase as shareholder rights weaken, the degree of dividend smoothing behavior is primarily a function of the habit persistence of corporate managers while share repurchases are largely discretionary corporate payout events (Lintner, 1956; Fama and Babiak, 1968; Brav, Graham, Harvey, and Michaely, 2005; Campello, Graham, and Harvey, 2010; Leary and Michaely, 2011; Michaely and Roberts, 2011; Dittmar and Field, 2015).

Lambrecht and Myers (2015) further develop this theoretical model to introduce endogenous investment decisions. Even if corporate investment is highly lumpy or volatile over time, both dividend payout and managerial rent remain smooth. This smoothness can be at least partially achieved through pro-cyclical precautionary cash stockpiles that vary throughout the macroeconomic cycle. To the extent that corporate managers underinvest due to a lack of financial flexibility in the form of debt capacity or equity issuance when the firm experiences a severe macroeconomic downturn, this chain reaction triggers a first-order impact on the firm’s capital structure choice. Through the lens of managerial rent protection in corporate governance, this uniform field theory of corporate finance closely connects corporate investment, capital structure, cash resource development, and payout management in a coherent financial ecosystem.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2023-08-28 08:26:00 Monday ET

Jared Diamond delves into how some societies fail, succeed, and revive in global human history. Jared Diamond (2004) Collapse: how societies

2018-10-17 12:33:00 Wednesday ET

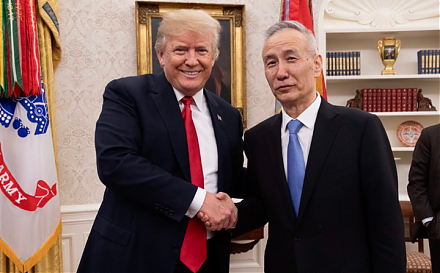

The Trump administration blames China for egregious currency misalignment, but this criticism cannot confirm *currency manipulation* on the part of the Chin

2019-03-05 10:40:00 Tuesday ET

We may need to reconsider the new rules of personal finance. First, renting a home can be a smart money move, whereas, buying a home cannot always be a good

2025-07-01 13:35:00 Tuesday ET

In recent times, financial deglobalization and asset market fragmentation can cause profound public policy implications for trade, finance, and technology w

2023-02-28 11:30:00 Tuesday ET

The Biden Inflation Reduction Act is central to modern world capitalism. As of 2022-2023, global inflation has gradually declined from the peak of 9.8% d

2017-02-19 07:41:00 Sunday ET

In his recent book on personal finance, Tony Robbins recommends that each investor should rebalance his or her investment portfolio *only once a year* to in