2022-04-15 10:32:00 Fri ET

mergers acquisitions corporate finance baker and wurgler managerial entrenchment jarrad harford corporate governance corporate investment corporate social responsibility rent protection ceo overconfidence board connections capital expenditures david hirshleifer ronald masulis andrei shelifer lucian bebchuk ulrike malmendier

This review of corporate investment literature focuses on some recent empirical studies of M&A, capital investment, and R&D innovation. This focus spans the empirical evidence in support of the misvaluation and q-theories of takeovers (Dong, Hirshleifer, Richardson, and Teoh, 2006), the effect of anti-takeover provisions on bidder returns around major acquisition announcements (Masulis, Wang, and Xie, 2007), the managerial entrenchment theory for M&A value destruction (Harford, Humphery-Jenner, and Powell, 2012), the complex nexus between CEO overconfidence and corporate investment (Malmendier and Tate, 2005, 2008; Hirshleifer, Low, and Teoh, 2012), and the relation between acquirer-target connections and merger outcomes (Cai and Sevilir, 2012; Ishii and Xuan, 2014). Some subsequent discussion touches on the central theme of stock-market-driven acquisitions in behavioral finance (Shleifer and Vishny, 2003; Baker, Pan, and Wurgler, 2012). The literature review paints several coherent tiles in the complete mosaic of corporate investment management.

Dong, Hirshleifer, Richardson, and Teoh (2006) document evidence in support of the misvaluation and q-theories of takeovers. The misvaluation theory holds that market inefficiency has important effects on takeover activity. These effects stem from the bidder’s efforts to profit by buying undervalued targets for cash at market prices below their fundamental values, or by paying equity for targets that are less over-valued than the bidder (Shleifer and Vishny, 2003). Moreover, the q-theory of takeovers focuses on how acquisitions deploy target assets. High market valuation reflects that a firm is well run with good growth opportunities. Therefore, relative market values are proxies for growth opportunities for both the bidder and the target. Takeovers may be designed to take advantage of better acquirer investment opportunities with minimal wasteful target engagement. Alternatively, takeovers may be viewed by the incumbents of an inefficient bidder as an opportunity to expand their domains of control. Dong, Hirshleifer, Richardson, and Teoh (2006) establish several empirical regularities that bolster both the misvaluation and q-theories of takeovers:

Dong, Hirshleifer, Richardson, and Teoh (2006) and Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) confirm Loughran and Vijh’s (1997) study of acquirer returns around takeover announcements that stock acquisitions attract negative abnormal bidder returns around merger announcements while cash acquisitions attract positive abnormal bidder returns around merger announcements. Bidder and target market values (price-to-book or price-to-residual-income) significantly correlate with means of payment, mode of acquisition, target premium, target hostility, offer success, and bidder and target returns around takeover announcements.

A body of corporate governance literature suggests a negative nexus between anti-takeover provisions (ATPs) and both firm values and long-term stock returns (Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick, 2003; Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell, 2009). ATPs give rise to higher agency costs through some combination of inefficient investment, lower operational efficiency, and managerial self-dealing behavior. Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) directly investigate the impact of a firm’s ATPs on its investment efficiency, or specifically, the shareholder wealth effect of its corporate acquisitions. Acquisition announcements made by firms with more ATPs in place yield significantly lower abnormal bidder returns than acquisition announcements made by firms with fewer ATPs.

Moreover, Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) examine the separate impact of external or internal corporate governance mechanisms such as product market competition, board composition such as board size and independence and CEO-chairman duality, as well as operating performance (as a proxy for management quality). Firms that operate in more competitive industries make better acquisitions with larger abnormal bidder returns, as do firms that separate the positions of CEO and chairman of the board.

Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) can identify an important channel through which takeover defenses erode shareholder value. ATPs allow corporate incumbents to make unprofitable acquisitions without facing a serious threat of losing corporate control. Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) also contribute to the literature on corporate governance by highlighting the importance of the market for corporate control in providing managerial incentives to increase shareholder wealth. This contribution expands the array of corporate governance mechanisms and so pertains to the empirical studies of Bebchuk and Cohen (2005), Cremers and Nair (2005), and Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell (2009).

As the largest and most readily observable form of corporate investment, acquisitions tend to intensify the conflict of interest between corporate incumbents and shareholders in large public corporations (Berle and Means, 1932; Jensen and Meckling, 1976). Incumbents may not always make profitable acquisitions. Often incumbents reap private benefits of control at the detriment of minority shareholders. Incumbents extract large benefits from their empire-building attempts, thus firms with abundant free cash flows but few profitable investment opportunities are more likely to engage in M&A and capital over-investments (Jensen, 1986; Lang, Stulz, and Walking, 1991).

By substantially delaying the takeover process and thereby raising the costs of a hostile acquisition, ATPs reduce the likelihood of a successful takeover and hence the incentives of potential acquirers to launch a bid (e.g. Bebchuk, Coates, and Subramanian (SLR 2002)). ATPs undermine the ability of the market for corporate control to perform its ex post settling-up function. The conflict of interest between incumbents and investors is more severe at firms with more ATPs or firms that are less vulnerable to hostile takeovers.

The IRRC publications cover 24 anti-takeover provisions from which Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick (2003) construct the governance index by adding one point for each provision that enhances managerial power. High G-index firms with more ATPs yield lower long-run stock returns and firm values (Gompers, Ishii, and Metrick, 2003). Bebchuk, Cohen, and Ferrell (2009) extend these results by creating a more parsimo-nious entrenchment index based on the 6 major provisions that are most important from a legal standpoint: staggered boards, poison pills, golden parachutes, supermajority requirements for mergers, and limits to shareholder bylaw amendments and charter amendments.

In the above context, Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) deduce the hypothesis of ATP value destruction: incumbents with more ATP insulation are more likely to engage in acquisitions that do not contribute to shareholder wealth maximization. Acquisition announcements made by firms with more ATPs in place produce significantly lower abnormal bidder returns than acquisition announcements made by firms with fewer ATPs. Each additional anti-takeover provision reduces bidder shareholder value by about 0.1%. As a typical dictatorship firm has 10 more ATPs than a typical democracy firm, the former underperforms the latter by about 1%, which is non-trivial relative to the mean cumulative abnormal return around the acquisition announcement of 0.215% (e.g. board classifications correspond to a mean shareholder value loss of $30 million).

Product market competition has a positive disciplinary effect on managerial behavior (Leibenstein, 1966; Hart, 1983; Shleifer and Vishny, 1997). Incumbents of firms that operate in competitive industries are unlikely to divert valuable corporate resources into inefficient uses. In more competitive industries, the margin for error is thin and any missteps can be quickly exploited by competitors. In turn, these missteps jeopardize firms’ prospects for survival. Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) use the Herfindahl-Hirschman index as a proxy for industry competition and the industry’s median ratio of selling expenses to sales as a proxy for product uniqueness (Titman and Wessels, 1988). Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) document a positive relation between product market competition and bidder return performance.

The board of directors serves as an important internal control mechanism. CEO-chairman duality, board size, and board independence are key characteristics that affect how effectively the board functions (Core, Holthausen, and Larcker, 1999; Hermalin and Weisbach, 2003). Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) find a negative nexus between CEO-chairman duality and bidder stock return performance. Separating the CEO and chairman positions helps rein in empire-building attempts by CEOs. As a consequence, these CEOs become more selective in their acquisition decisions that lead to greater shareholder wealth.

Less able CEOs make poor acquisitions and adopt ATPs to entrench themselves. A common practice is to measure bidder CEO quality by industry-adjusted operating income growth over the 3 years prior to the acquisition announcement (Morck, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1990). Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) find a positive relationship between bidder management quality and short-run stock return performance. Thus, CEOs of better management quality make better acquisitions in the best interests of shareholders.

Masulis, Wang, and Xie’s (2007) study of short-run abnormal bidder returns reinforces the prior evidence that firms with fewer ATPs generate better long-run shareholder value in comparison to firms with more ATPs (Cremers and Nair, 2005; Core, Guay, and Rusticus, 2005). Overall, Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) find empirical support for the hypothesis of ATP value destruction: incumbents with more ATP insulation are more likely to engage in acquisitions that do not contribute to shareholder wealth maximization. In essence, acquisition announcements made by firms with more ATPs in place produce significantly lower abnormal bidder returns than acquisition announcements made by firms with fewer ATPs.

Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007) find that excessive managerial entrenchment with takeover defenses has a first-order negative impact on bidder value. Harford, Humphery-Jenner, and Powell (2012) extend this logic and empirically demonstrate that a significant portion of merger value destruction arises from the avoidance of private targets with better ex post managerial entrenchment. When incumbents that receive better insulation from anti-takeover provisions target private firms, these incumbents primarily use cash. This cash payment effectively helps avoid both the potential creation and scrutiny of future blockholders. This rationale also applies to the acquisition of public firms. Incumbents that benefit from more takeover defenses prefer not to use stock when their companies acquire public companies with large blockholders. Nonetheless, target form is not the whole explanation for merger value destruction because on average incumbents that benefit from more takeover defenses make unprofitable acquisitions.

Harford, Humphery-Jenner, and Powell (2012) use the Heckman (1979) sample selection model to affirm that the binary flag for anti-takeover dictatorship has a significantly negative impact on the likelihood of acquiring private targets, acquiring private targets entirely with stock, or acquiring targets with at least 5% blockholder ownership. Harford, Humphery-Jenner, and Powell (2012) apply Officer’s (2007) proxy premium regressions of 5-day cumulative abnormal returns on the binary flag for anti-takeover dictator-ship, the dummy variable for all-stock takeover, the interaction between the dictatorship dummy variable and the proxy premium, and an array of control variables. Ceteris paribus, the dummy variables and the interaction term all carry significantly negative coefficients. This evidence suggests both overpayment and poor target selection as plausible explanations for merger value destruction.

All merger value destruction involves overpayment. Greater managerial entrenchment usually results in worse post-merger operating performance in the Healy-Palepu-Ruback (1992) regressions of industry-adjusted ROAs on the governance or entrenchment index and a set of control variables for the complete sample and different anti-takeover subsamples. This evidence suggests that substandard target selection, rather than only overpayment, explains most merger value destruction. In sum, incumbents that are secure with more takeover defenses often seek to preserve their entrenchment through deliberate target selection.

Malmendier and Tate (2008) provide empirical evidence in support of the view that overconfident CEOs overestimate their ability to promote shareholder value. As a result, these overconfident CEOs overpay for target companies and undertake mergers that destroy shareholder value. For this analysis, Malmendier and Tate (2008) consider both each CEO’s personal overinvestment in the company and his or her press portrayal. The former includes both binary indicators of Longholder and Holder 67 while the latter is a proxy for the market perception of CEO overconfidence with keyword press coverage in major business publications such as The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times, BusinessWeek, Financial Times, and The Economist. Furthermore, the first indicator variable, Longholder, identifies CEOs who, at least once during their tenure, hold an option until the year of expiration, even though the option is at least 40% in-the-money in its final year. The second indicator variable, Holder 67, is equal to unity if a CEO fails to exercise his or her options with at least 5 years of residual duration despite a 67% increase in the stock price (or more) since the grant date (and zero otherwise).

In effect, CEO overconfidence predicts more mergers and acquisitions when the CEO does not need to access external capital markets to finance the deal. In firms with large excess cash or spare risk-free debt capacity, only the overestimation of operational synergies has a first-order impact on the merger decisions of over-confident CEOs. This overestimation in turn results in a higher M&A premium. Malmendier and Tate (2008) report empirical evidence to substantiate the main predictions below:

Malmendier and Tate’s (2008) empirical study contributes to several lines of corporate finance literature. First, Malmendier and Tate (2008) contribute to the agency theory for mergers and acquisitions because corporate managers who hold abundant internal resources tend to be more acquisitive to the detriment of shareholders (Jensen, 1986; Harford, 1999). Unlike traditional empire-builders, however, overconfident CEOs believe that they act in the best interests of shareholders. As a consequence, these overconfident CEOs are willing to personally overinvest in their companies. While excessive acquisitiveness can result both from agency conflict and from CEO overconfidence, the relation to late option exercise (i.e. CEOs’ personal overinvestment in their companies) arises only from CEO overconfidence. CEO overconfidence serves as an alternative explanation for the origin of both agency costs and private benefits of control. In this light, standard incentive contracts such as stock compensation are unlikely to correct these overcon-fident CEOs’ suboptimal M&A decisions. Yet, overconfident CEOs do respond to financial constraints. Thereby, debt overhang or similar capital structure constraints can help discipline overconfident CEOs. In addition, independent directors may need to play a more active role in project assessment and selection to counterbalance CEO overconfidence.

Moreover, Malmendier and Tate (2008) contribute to the growing strand of behavioral corporate finance literature. In efficient markets, corporate managers who suffer from systematic biases can often engage in suboptimal value diversion (Barberis and Thaler, 2003; Baker, Ruback, and Wurgler, 2006; Baker and Wurgler, 2012). In the context of corporate mergers and acquisitions, CEOs who maintain high personal exposure to company risk are more acquisitive, especially when their firms have abundant cash resources. As a result, these overconfident CEOs tend to conduct unprofitable mergers and acquisitions that destroy shareholder value. The negative impact of CEO overconfidence on M&A value creation complements the conjecture that CEO overconfidence accounts for corporate investment distortions (Malmendier and Tate, 2005). CEO overconfidence highly correlates with a greater sensitivity of corporate investment to cash flow, particularly among equity-dependent firms. These investment distortions reflect the dark side of managerial overconfidence.

Overconfident individuals often overestimate the net present value of uncertain endeavors, either because of a general tendency to expect good outcomes, or because these individuals overestimate their efficacy in bringing about success. Furthermore, people tend to be more overconfident about their performance on hard tasks rather than easy tasks (Griffin and Tversky, 1992). As a consequence, Hirshleifer, Low, and Teoh (2012) expect relatively overconfident CEOs to be especially enthusiastic about risky and talent- and vision-sensitive enterprises. Innovative R&D investment projects apply new business methods, offer new products or services, or develop new technologies. These relatively risky and intangible investment projects attract overconfident CEOs who are more likely to undertake these projects. Adopting innovative R&D investment projects may be viewed as indicative of superior managerial vision and competence. In accordance with this rationale, innovative R&D projects are likely to appel to self-aggrandizing managers.

Using both option and press measures of CEO overconfidence, Hirshleifer, Low, and Teoh (2012) report that firms with overconfident CEOs have greater stock return volatility, invest more in R&D innovation, obtain more patents and patent citations, and achieve greater innovative success for R&D expenditures. However, overconfident CEOs achieve greater R&D innovation only in innovative high-tech industries. The evidence lends credence to the bright side of CEO overconfidence that overconfidence helps CEOs exploit innovative R&D growth opportunities.

Hirshleifer, Low, and Teoh (2012) succinctly summarize the extant literature on the impact of CEO over-confidence on a variety of corporate outcomes:

Malmendier, Tate, and Yan (2011) empirically assess the role of managerial traits in explaining the time-invariant component of capital structure (Lemmon, Roberts, and Zender, 2008). Managerial traits such as overconfidence reflect the CEO's early-life experiences, for instance, military service and adulthood in the Great Depression. Malmendier, Tate, and Yan (2011) substantiate the main hypotheses below:

In summary, overconfident CEOs prefer internal finance over external finance and, conditional on raising risky capital, debt over equity. Also, CEOs who experienced the Great Depression early in life display a heightened reluctance to access external capital markets. With respect to some other aspect of early-life experience, CEOs with a military background choose more aggressive corporate policies such as higher leverage ratios. Complementary measures of managerial personality traits that arise from press portrayals confirm these results.

Having a board connection between two firms helps enhance both information flow and communication between the firms. This communication increases each firm’s knowledge of the other firm’s business and corporate culture. This information advantage in turn may lead to a better M&A transaction between the two firms. The information advantage may also affect the takeover premium and so the transaction price of the deal. Cai and Sevilir (2012) consider two types of board connections between the bidder and target firms. The first type is *first-degree board connection* where the bidder and target firms share a common director before the deal announcement. The second type is *second-degree board connection* where one director from the acquirer and one director from the target have been serving on the board of a third firm before the deal announcement. Cai and Sevilir’s (2012) Python web-crawling algorithm searches for both first-degree and second-degree board connections in both the acquirer’s and target’s proxy statements. In the full sample of 1,664 M&A deals from 1996 to 2008, 65 out of 156 board-connected transactions have first-degree board connections while the other 91 transactions have second-degree board connections.

Cai and Sevilir (2012) empirically find that both first-degree and second-degree board connections have a positive effect on the 5-day cumulative abnormal bidder return around the acquisition announcement. Specifically, the difference in average acquirer returns between the sample firms with and without first-degree board connections is a hefty 2.45% (p-value<0.05). Also, the difference in average bidder returns between the sample firms with and without second-degree board connections is 1.84% (p-value<0.05). In the presence of first-degree board connections, the average takeover premium is lower and becomes even lower when the first-degree board connection pertains to an executive director at the acquirer firm. To the extent that executive directors gain favorable information asymmetries and incentives to undertake the M&A deal at a lower price in comparison to outside directors, this result supports the view that first-degree board connections provide the bidder with a clear information advantage to acquire the target at a more attractive price. Furthermore, the takeover premium in first-degree connections is lower when the number of competing bidders is smaller. First-degree board connections thus allow the acquirer to have better bargaining power in deal negotiations by providing both directors with favorable information about the target and by limiting the degree of competition from outside bidders who lack material information about the target. In comparison to the information advantage of first-degree board connections, second-degree board connections result in a substantive improvement in post-deal operating performance with a 1.9% increase in industry-adjusted ROA. In essence, first-degree board connections benefit most bidders with lower takeover prices while second-degree board connections benefit most bidders with shareholder value creation in the form of a significant improvement in industry-adjusted ROA. Both types of board connections help attract positive bidder returns around merger announcements ceteris paribus.

In contrast to Cai and Sevilir’s (2012) evidence that professional board connections present at the time of the acquisition announcement have a positive effect on bidder returns, Ishii and Xuan (2014) find that social ties between the bidder and target firms have a negative impact on bidder returns. Incumbents who know each other through school or past work would not necessarily be better informed about the prospect of a deal between their current firms. Also, the social ties between incumbents of the acquirer and target firms significantly raise the likelihood that the target firm’s CEO and directors remain in their respective positions after the merger. An individual target director is more likely to be retained on the post-merger board if this target director has more social ties to the acquirer’s directors, officers, and senior managers. Acquirer CEOs are more likely to receive hefty bonuses and are more richly compensated for completing mergers with targets that are socially connected to the acquirer. Furthermore, acquisitions are more likely to occur between the acquirer and target firms that have strong social ties. In essence, social ties between the bidder and target firms lead to poor merger decisions with lower overall shareholder value.

Shleifer and Vishny (2003) derive and develop a unified field theory of mergers and acquisitions. In this theory, merger deals are primarily driven by the stock market valuation of both bidder and target firms. To the extent that the stock market may occasionally misvalue potential acquirers, potential targets, and their combinations, corporate managers can take advantage of these market price discrepancies through merger decisions. In practice, the stock market does not correctly react to the news of an M&A deal since acquirers that make cash tender offers earn positive long-run abnormal returns while acquirers that make stock acquisitions earn negative long-run abnormal returns (Loughran and Vijh, 1997). Rau and Vermae-len (1998) confirm that this pattern persists even after the correction for both size and book-to-market in the spirit of Fama and French (1993). Glamour bidders overpay more frequently with stock than do value bidders (Martin, 1996; Rau and Vermaelen, 1998).

Shleifer and Vishny’s (2003) theoretical model explains the ubiquitous empirical regularities of mergers and acquisitions. The main ingredients are the relative market values of both the bidder and target firms and the operational synergies that the market perceives to materialize from the merger. Several theoretical predictions of Shleifer and Vishny’s (2003) model accord with the empirical evidence on merger deals:

Salient but largely irrelevant reference point stock prices of the target firm play a key role in mergers and acquisitions through the prices, quantities, and likelihood of deal success (Baker, Pan, and Wurgler, 2012). The psychological motivation has key roots in the anchoring-conservative-adjustment estimation method (Tversky and Kahneman, 1974), the salience of initial anchor positions in negotiations, and the prospect theory tenet that the utility of an outcome is a function of the distance between the status quo and some reference point (Kahneman and Tversky, 1979). The 52-week high prices, for instance, serve as salient reference points for senior managers, directors, and outside investors in M&A valuation. In contrast to the individual cost bases of target shareholders, the 52-week peak prices are reference points that tend to be common among major corporate stakeholders. Target firm boards that discourage an M&A deal often point out that the bid is less than the recent peak stock price while target-firm boards that encourage an M&A deal often note when the bid compares favorably with the recent peak stock price.

Baker, Pan, and Wurgler (2012) empirically find that for 52-week peak prices of a typical size, a 10% increase in the 52-week high price highly correlates with a 3.3% increase in the offer premium after the econometrician controls for a variety of bidder, target, and deal characteristics. This effect of peak prices on M&A offer prices survives a unique set of control variables, robustness checks, and falsification tests. Further, higher offer prices significantly correlate with higher probabilities of deal success. An additional dummy variable indicates that the probability of deal success increases discontinuously by 4.4%-6.4% when the bidder makes an offer price even slightly above the target firm’s 52-week high stock price. In addition, the bidder’s announcement effect becomes more negative with the target firm’s distance from its 52-week peak stock price. The acquirer’s merger announcement effect is about 2.45% worse for each 10% increase in the component of offer premium that can be explained by the 52-week high stock price.

Merger waves coincide with higher recent stock returns and stock market values. The market’s 52-week high price relative to its current value is inversely related to the number of mergers and acquisitions. In effect, the evidence echoes the market-timing theories of mergers and acquisitions by Shleifer and Vishny (2003) and Rhodes-Kropf and Viswanathan (2004).

According to the novel view of stakeholder value maximization, corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities can have a positive effect on shareholder wealth because focusing on the common interests of other stakeholders increases their willingness to support a firm’s business operation. In turn, this support contributes to greater shareholder wealth (Coase, 1937; Cornell and Shapiro, 1987; Hill and Jones, 1992). Using a large dataset of mergers with KLD CSR scores, Deng, Kang, and Low (2013) examine whether CSR creates value for the acquirer firms’ shareholders. In comparison to low-CSR acquirers, high-CSR acquirers realize higher bidder returns around acquisition announcements, higher bidder-target portfolio returns around merger announcements, and greater increases in long-term operating performance in the post-merger period.

Because CSR investments are likely to increase the typical firm’s intangible assets, the full value of CSR might not be incorporated into the stock price around the merger announcement date. While high-CSR acquirers are likely to experience higher post-merger long-term stock returns than low-CSR acquirers, the post-merger improvement in firm performance takes time to materialize in due course. According to Deng, Kang, and Low (2013), mergers by high-CSR acquirers take much less time to complete and are less likely to fail than mergers by low-CSR acquirers. In this light, the CSR performance of acquirers is a major determinant of both merger default likelihood and ex post bidder-target performance.

In their empirical analysis of the relation between a firm’s CSR activity and merger outcome variables, Deng, Kang, and Low (2013) address the potential endogeneity of CSR engagement via 2SLS regressions in which both the religion rank of the state of the bidder’s headquarters and a blue-state dummy variable serve as relevant and exclusive instrumental variables. In essence, these instruments correlate with CSR engagement but not the merger outcome variables such as bidder stock return performance and merger default likelihood. Several control variables for product market competition, corporate governance, and managerial compensation echo the prior corporate finance literature (e.g. Masulis, Wang, and Xie (2007); Edmans, Gabaix, and Landier (2009)). The preponderance of Deng, Kang, and Low’s (2013) empirical results suggests that the typical firm integrates multiple stakeholder interests in the business operation to engage in profitable corporate investment activities. This evidence supports the novel view of stakeholder value maximization.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

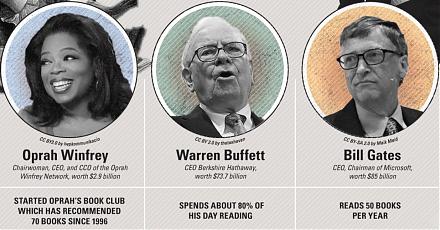

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2023-08-14 09:25:00 Monday ET

Peter Isard analyzes the proper economic policy reforms and root causes of global financial crises of the 1990s and 2008-2009. Peter Isard (2005) &nbs

2018-08-11 14:35:00 Saturday ET

The Trump administration imposes 20%-50% tariffs on Turkish imports due to a recent spat over the detention of an American pastor, Andrew Brunson, in Turkey

2025-10-06 10:27:00 Monday ET

Stock Synopsis: With a new Python program, we use, adapt, apply, and leverage each of the mainstream Gemini Gen AI models to conduct this comprehensive fund

2021-02-02 14:24:00 Tuesday ET

Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms the major stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq. We implement

2019-05-13 12:38:00 Monday ET

Brent crude oil prices spike to $70-$75 per barrel after the Trump administration stops waiving economic sanctions on Iranian oil exports. U.S. State Secret

2018-07-11 09:39:00 Wednesday ET

In recent times, the Trump administration sees the sweet state of U.S. economic expansion as of early-July 2018. The latest CNBC All-America Economic Survey