2023-03-21 11:28:00 Tue ET

treasury deficit debt employment inflation interest rate macrofinance fiscal stimulus economic growth fiscal budget public finance treasury bond treasury yield sovereign debt sovereign wealth fund tax cuts government expenditures

Barry Eichengreen (2016)

Berkeley macro economist Barry Eichengreen compares the Great Depression of the 1930s to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. Eichengreen analyzes these economic episodes from a historical Keynesian perspective. Fiscal macro policies that increase aggregate demand would have promoted a much stronger and faster economic recovery from the Great Recession in each episode. On the other hand, neoclassical supply-side factors can further contribute to economic revival in each episode. The U.S. Treasury and Federal Reserve System would need to fund large fiscal stimulus programs and tax credits with substantial deficits to curtail the depth and duration of the Great Recession soon after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. The parallel fine distinction between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 provides plenty of intellectual justification for greater government expenditures.

From a neoclassic perspective, however, these economic episodes fundamentally differ in terms of productivity changes. The global economy has shifted onto lower steady-state growth paths after the respective recessions. Key post-crisis recovery returns to the longer-term trend of total output several years after each respective recession. Yet, no or low productivity growth remains a major concern among most OECD countries in the decade right after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. The new normal steady state seems to be different this time. Despite such different views on the macroeconomic root causes of these unique episodes, Eichengreen provides trenchant comparisons between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

In both episodes, macroeconomic policies and institutions promote greater public debt accumulation, risk tolerance, and unsustainably high asset return volatility. In effect, Eichengreen regards these macroeconomic policies and institutions as one of the major fundamental sources of the crises. The crises turn out to be practically relevant to the resultant recessions both in the 1930s and 2008-2009. Insufficient aggregate demand accounts for the economic depth and duration of both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

The Eichengreen thesis of Hall of Mirrors serves as a natural sequel to his previous book Golden Fetters (1992) on the Great Depression back in the 1930s. In Golden Fetters, Eichengreen indicates that worldwide monetary contraction serves as the exogenous consequence of the gold standard. The macroeconomic event can help explain the income and employment losses in the Great Depression of the 1930s. Better macroeconomic responses would require international coordination of more government expenditures with no or little deflationary bias.

In the more recent analysis Hall of Mirrors (2016), Eichengreen applies traditional Keynesian logic to reinterpret stark comparisons between the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009. The Keynesian concept of insufficient aggregate demand becomes the central primitive object in the in-depth analysis of both recessions. Fiscal stimulus policy measures such as the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 rely on no economic theory. Nonetheless, many economists would expect the fiscal stimulus programs to expand aggregate demand. These fiscal stimulus responses connect more closely with Keynesianism than modern research on monetary policy, inflation, and the business cycle. Both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009 are pathological events that move beyond the current scope of the real business cycle theory by Finn Kydland, Ed Prescott, Robert Barro, Robert King, Charles Plosser, Sergio Rebelo, and many more.

Eichengreen omits macro models from his book Hall of Mirrors. The omission limits the analytical contributions of the traditional Keynesian thesis on both episodes of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009. Key dynamic stochastic general equilibrium (DSGE) macro models help explain severe recessions because these macro models do not necessarily feature Pareto optimal results. Insofar as most asset markets clear in a Walrasian manner, these models serve as discipline devices that empower most economic researchers to determine whether several economic insights (such as monetary neutrality and intertemporal substitution) prove to be internally consistent in stochastic calibration and empirical work. What might seem to be an obvious argument outside of a macro model can be far from obvious within the same model. These macro models resist delivering what we want if the desirable results depart very much from sensible choices made by most economic actors. For instance, some economists argue that lower wealth can depress the global economy by reducing aggregate demand. However, most macro models indicate that lower wealth reduces the demand for all normal goods such as leisure and consumption. From time to time lower wealth tends to increase labor supply ceteris paribus.

It often becomes difficult for most macro economists to generate severe recessions within an explicit macro model if no structural changes impede the incentives and opportunities for trade, production, and capital investment accumulation etc. These structural changes relate to taxes, dividends, regulations, technological advances, and other efficiency gains. Some macro economists manage to engineer a severe recession with deflation through a macroeconomic taste shock that helps dampen current consumption in a standard macro model. With nominal price imperfections, the relevant margins of intertemporal substitution cannot adjust in a flexible fashion. Fully cutting off intertemporal substitution margins is the key to generating a severe and persistent recession in this particular economic environment. In the stochastic macro model calibration, the severe recession manifests in the form of persistent declines in economic output, consumption, employment, and capital accumulation (Eggertsson, 2011).

From the Great Depression of the 1930s to the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009, productivity changes differ considerably between these episodes. Productivity falls substantially during each severe recession and then gradually returns to the new normal steady state of total factor productivity many years later. A major difference between both episodes reveals that such productivity retrenchment persists by 7% below the long-term trend of total factor productivity even 7-8 years after the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009. In the years from 2009 to 2015, substantially subpar economic growth indicates a persistently weak global economy several years after the Global Financial Crisis.

Neoclassic studies of severe recessions often begin with the practical application of business cycle analysis. This analysis identifies a large productivity decline and a labor wedge that collectively account for the economic downturn (1920-1933 or 2008-2009). The labor wedge is the percentage change in the standard atemporal Euler first order condition that theoretically equates the marginal rate of substitution between consumption and leisure to the marginal product of labor. Plugging output, labor, and consumption data into the key Euler first-order condition with logarithmic preferences over consumption and leisure as well as a Cobb-Douglas production function yields a marginal rate of substitution that can be about 30% lower than the marginal product of labor. This quantitative result shows a large distortion to either the incentives or the opportunities for economic actors to trade labor services. Key structural changes in competitive forces and factors distort this first-order condition. As a result, antitrust competition rules and regulations have changed significantly since the 1930s.

One potential reason for the difference between the Eichengreen views of the New Keynesian macro models is that these New Keynesian models share relatively no or little with the classic Keynesian approach of Hall of Mirrors. The New Keynesian macro models rely on a complete suite of 3 main equations. First, gradual interest rate adjustments can cause first-order negative effects on the output gap. Second, there is a mysterious and inexorable trade-off between inflation and unemployment. Third, nominal risk-free interest rate changes respond to both changes in inflation and the output gap to the respective target levels. This modern Keynesian analysis of fiscal expansion relies on macro environments of a zero marginal propensity to consume in hard times. Fiscal expansion works well in practice by getting around the zero lower nominal interest rate bound. The fiscal expansion often depends on persistently lower real interest rates. An explicit macroeconomic framework would have helped clarify the Eichengreen views on the Hoover and Roosevelt antitrust competition policies. This Keynesian assessment of antitrust rules and regulations differs from the New Keynesian policy implications of the severe recession in each episode of the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis 2008-2009.

Through his thesis of Hall of Mirrors, Eichengreen places the primary blame for the severe recession on financial crises but not antitrust competition policies. This key thesis extends back to at least Friedman and Schwartz (1963) that financial crises might have contributed to the Great Depression of the 1930s. However, some data raise empirical questions about the quantitative relevance of these financial crises in practice.

One of the major issues is reverse causation. The Great Depression might be well underway before the financial crises. Friedman and Schwartz (1963) cite the first financial crisis as of November 1930 after a 35% decrease in industrial production. The financial crises might be consequences of the Great Depression of the 1930s (not the causes of the Great Depression). This economic insight further applies to the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

Another fundamental issue pertains to the size of the external shock in association with the financial crises. The Great Depression of the 1930s and Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 both result in substantial losses of bank capacity. As financial distress might serve as a major fundamental factor, most financial institutions and deposit takers would have strong incentives to preserve large core capital buffers instead of distributing cash dividends and share repurchases to bank shareholders. From this fundamental viewpoint, most banks and other financial institutions would need to hold substantially higher equity capital requirements in order to safeguard against extreme losses that might arise in rare times of severe financial stress. In summary, the large losses of bank capacity often tend to manifest in the substantial depletion of equity capital buffers for most banks and other financial institutions. In this fundamental view, bank capital declines exacerbate the adverse impact of the external shock in both the Great Depression of the 1930s and the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009.

Standard models of financial crises by Bernanke, Gertler, and Gilchrist (1999) etc cannot generate labor supply declines. Neither can these macro models generate post-crisis productivity losses. Hence, we have no general theory of the behavior of the labor market of the decade from 2008 to 2017. Moreover, we lack a general theory of chronic productivity decline. This lack of theory suggests that fiscal policy responses to the severe recessions (cf. the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 and Payroll Tax Holiday) often reflect the neoclassic economic insights of expanding aggregate demand through industry subsidization. Eichengreen and many other proponents argue that these fiscal stimulus policies turn out to be quite effective with a fiscal multiplier well above one.

Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009, the Federal Reserve System and Council of Economic Advisors have consistently predicted higher economic growth than actual growth. These forecast errors arise as the natural result of the economy shifting to a lower steady-state growth path such that many aggregate covariates such as output, labor, and capital etc have not recovered to their pre-crisis trends. Standard macro models of financial crises usually cannot generate a lower steady-state growth path for the economy. For this reason, the models are not informative for understanding this gradual transition to low steady-state economic growth. The source of total factor productivity decline thus becomes a major open question for understanding the lack of economic recovery from the Global Financial Crisis.

Tech-savvy startups are important for U.S. economic growth. These startups tend to be the main source of considerable disruptive innovation. Further, these startups are responsible for a disproportionate share of net job creation in America. Net job creation tends to be negative during an average year in the U.S. economy across all incumbent firms. The lower startup rate has important public policy implications for most economists to better understand U.S. economic growth. A small share of startups can grow exponentially for future generations of tech-savvy startups. Most of these tech startups and unicorns specialize in the high-tech fields of information technology (e.g. Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Intel, Oracle, SpaceX, Tesla, and many more). In essence, the global economy has shifted toward lower interest rates and productivity gains in recent decades. Eichengreen attributes these long-term structural changes to insufficient fiscal stimulus not only in North America but also in many parts of Asia and Europe. In contrast, several other macro economists regard supply-side factors such as productivity growth, resource reallocation, tech entrepreneurship, and immigration etc as the main root causes of macro economic retrenchment. On balance, the law of inadvertent consequences counsels caution when push comes to shove.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

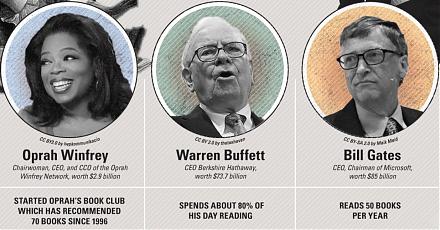

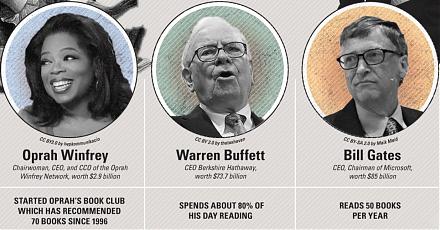

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2021-02-02 14:24:00 Tuesday ET

Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms the major stock market benchmarks such as S&P 500, MSCI, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq. We implement

2023-04-07 12:29:00 Friday ET

Timothy Geithner shares his reflections on the post-crisis macro financial stress tests for U.S. banks. Timothy Geithner (2014) Macrofinanci

2018-03-13 07:34:00 Tuesday ET

From crony capitalism to state capitalism, what economic policy lessons can we learn from President Putin's current reign in Russia? In the 15 years of

2023-07-28 11:28:00 Friday ET

Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried critique that executive pay often cannot help explain the stock return and operational performance of most U.S. public corpor

2019-01-27 12:39:00 Sunday ET

British Prime Minister Theresa May faces her landslide defeat in the parliamentary vote 432-to-202 against her Brexit deal. British Parliament rejects the M

2024-02-04 08:28:00 Sunday ET

Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms most stock market indexes from 2017 to 2024. Our proprietary alpha investment model outperforms the ma