2023-12-08 08:28:00 Fri ET

federal reserve monetary policy treasury deficit debt employment inflation interest rate fiscal stimulus economic growth central bank fomc global financial cycle tax cuts government expenditures

Economists often praise as pluralism the interplay of special interest groups in public policy. Interest group theory portrays public policy as the equilibrium in the struggle between special interest groups. This equilibrium need not be the same as the majority preference. Pluralists often view this equilibrium as the best possible approximation of the public interest in a large and diverse society. In America, more than one-half of all personal income escapes taxation through various exemptions, deductions, and special treatments in tax laws. Tax laws treat different types of income differently. These different tax laws penalize work and investment and divert capital investment into non-productive tax shelters and an illegal black economy. The unfairness and inefficiency of these complex tax laws arise from special interest groups. Political considerations sometimes may or may not adequately reflect these special interests in tax policy pluralism.

Since 2010, the top marginal tax rate has been 39.6% in America. Slightly more than half of the U.S. population pays income taxes. The personal income tax is the federal government’s largest single source of revenue. Since 2010, there are 7 progressive personal income tax brackets: 10%, 15%, 25%, 28%, 33%, 35%, and 39.6%. These tax rates apply progressively to income levels (or tax brackets), which stick to annual dollar indices to reflect inflation. The federal income tax is the pay-as-you-earn deduction from the paychecks of U.S. employees except farm and domestic workers. This withholding system is the backbone of the income tax. Many Americans often feel surprise to learn that almost half of all U.S. personal income escapes taxation. The U.S. tax laws draw a distinction between gross income (which is each person’s total money income minus personal work expenses) and taxable income (the part of gross income subject to taxation). Federal tax rates apply only to taxable income. Federal tax laws allow many reductions in gross income in the calculation of taxable income.

An Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) requires U.S. taxpayers to compute a separate AMT tax in addition to their regular income tax. U.S. taxpayers must pay whichever tax is higher. The AMT has a broader definition of taxable income and so disallows many standard deductions. This minimum tax can help ensure that higher income taxpayers with many exclusions and deductions should pay a minimum tax. In addition to multiple means of tax avoidance (legal means of escaping U.S. taxes), an underground economy that facilitates tax evasion (illegal means of dodging U.S. taxes) usually costs the federal government many billions of dollars. Independent estimates of the size of U.S. tax evasion place the loss at 15% of all taxes due.

The federal personal income tax is highly progressive. Together with personal and standard exemptions for families and income tax credits for lower-income earners, the 7 tax brackets combine to remove most of the tax burden from middle-income and low-income Americans. Indeed, the lower 50% of U.S. income earners pay only 3% of all U.S. federal income taxes. However, the burden of Social Security payroll taxes falls mostly on these low-income and middle-income workers in America. The top 10% of income earners pay 70% of all personal income taxes, and the top 1% of U.S. income earners pay 39% of all personal income taxes in America.

The second largest source of federal tax revenue comes from social insurance payroll taxes. Social insurance payroll taxes include Social Security and Medicare. Employers pay half of these taxes directly and withhold half from wages for employees. The Social Security tax is regressive in the sense that this tax captures a bigger proportion of the income of low-income earners than the income of higher-income earners in America.

The corporate income tax provides only less than 10% of the federal government’s total tax income. Federal and state corporate income taxes amount to almost 21% of total corporate income in America. The U.S. corporate income tax is notorious for its loopholes. Key special interest groups represent specific industries, and lobbyists represent individual corporations. These proponents have inserted many exemptions, deductions, and special treatments into U.S. corporate tax laws that most corporate profits escape taxation. Who pays the corporate income tax in America? Economists differ over whether corporations bear the tax burden or whether the corporate income tax ultimately goes to consumers in America. It is quite difficult to draw conclusive evidence on the incidence of corporate income taxation.

U.S. tax laws are complex and unfair in treating various sources of income differently. Many tax exemptions, deductions, and special treatments often turn out to be loopholes that allow high-income high-net-worth entities with privileges to escape fair income taxation. Tax laws sometimes encourage tax avoidance and then direct investment away from productive uses and into inefficient tax shelters. High marginal tax rates can discourage work and investment. Economic growth often becomes subpar when people face income tax rates of 50% or more. These economic considerations can help explain the intermediate optimal range of personal income tax rates.

A central issue in tax politics is the question of who bears the heaviest burden of a tax (i.e. which income groups should devote the largest proportion of their income to the payment of taxes). Progressive taxes usually require high-income groups to pay a larger percentage of their income in taxes than low-income groups. Proportional taxes require all income groups to pay the same percentage of their income in taxes. Regressive taxes require high-income groups to pay a smaller percentage of their income in taxes than low-income groups. Most taxes take more money from the rich than the poor. Whether a tax is relatively progressive or regressive depends on the percentages of income taken from various income groups. In America, a taxpayer with $400,000 in taxable income would not pay 35% of his or her total income in taxes. Rather, this taxpayer would pay approximately $119,000 in taxes (or about 30% of his or her total taxable income).

Many proponents defend progressive taxation on the baseline principle of ability to pay. The assumption is that high-income groups can afford to pay a larger percentage of their income into taxes. This assumption arises from marginal utility theory as it applies to money: each additional dollar of income is slightly less valuable to a person than all the preceding dollars. The government can tax additional dollars of income at higher rates with no or little violation of equitable principles.

Another general tax policy issue is universality. Under universal tax treatments, all types of income should be subject to the same tax rates, so corporate income should be subject to the same tax rates for personal income such as wages and bonuses. U.S. federal tax laws often distinguish ordinary income from capital gains (i.e. profits from the purchase and sale of property such as stocks, bonds, and real estate). The top U.S. marginal tax rate on capital gains is only 15%, whereas, the top U.S. marginal tax rate on personal income is 39.6%. As the real estate and asset market industries suggest, a lower rate of taxation on capital gains encourages better investment and economic growth.

In U.S. tax laws, thousands of exemptions, deductions, and special treatments often violate the principle of universality. Many high-net-worth people wish to retain all possible tax breaks through charitable deductions, child-care deductions, and home mortgage deductions. Key proponents of these popular tax treatments argue that they serve valuable social purposes (i.e. more charitable contributions, child-care subsidies, and home ownership stakes).

High tax rates discourage investment and economic growth. Excessively high tax rates may cause investors to seek tax shelters elsewhere. Around the world, some notable tax havens include Cayman Islands, Switzerland, Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Singapore, so forth. Many high-net-worth people use their money not to produce more business and employment, but rather to produce tax breaks for themselves. High tax rates discourage work and productive investment and then often tend to encourage tax avoidance (legal methods of reducing taxes) as well as tax evasion (illegal methods of reducing taxes).

In accordance with supply-side economics, tax cuts do not necessarily create government deficits. If the government reduces tax rates, the result may be to increase government tax revenue because more people would work much harder to start new businesses with greater profits. This additional economic activity would produce more government tax revenue even though tax rates were lower. Economist Arthur Laffer developed the Laffer curve of optimal taxation. If the government imposed a zero tax rate, the government would receive no tax revenue. Initially, government tax revenue would rise with marginal increases in the tax rate. But higher tax rates would discourage workers and businesses from productive employment. If this discouragement occurs, the economy and government tax revenue both decline over time. Laffer did not claim to know what the optimum rate of income taxation should be, but he and the Reagan administration believed that America had been in the prohibitive range of tax rates prior to the 1980s.

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 was one of the most heavily lobbied pieces of legislation in the history of U.S. Congress. President Reagan offered this reform bill as a trade-off: a reduction in tax rates in exchange for the elimination of many tax breaks. The baseline rate structure transformed 14 tax brackets from 11% to 50% down to only 2 tax brackets of 15% and 28%. The elimination of exemptions, deductions, and special treatments helped make up for lost tax revenue. However, powerful special interest groups fought hard against giving up their tax breaks in order to lower taxes. President Reagan finally succeeded in pushing Congress to reduce tax rates to 2 simple tax brackets of 15% and 28%. On balance, the special interest groups succeeded in retaining many of their favorite exemptions, deductions, and special treatments. The act prevented taxpayers from using passive losses from capital investments to reduce other income for tax purposes. In addition, this act eliminated many kinds of tax shelters. The real estate industry (of builders, developers, and mortgage lenders) succeeded in restoring deductions for vacation homes. The oil and natural gas industry succeeded in retaining most of their special preferences in the tax laws (such as depletion allowances and intangible drilling costs). The banking industry lost their fight to retain interest deductions on auto and consumer loans. The restaurant and entertainment industries restored 80% of their favorite tax deductions. State and local governments were successful in keeping exemptions from the taxation of interest income from their municipal bonds.

In 1988, George H.W. Bush campaigned for the U.S. presidency with an emphatic promise to veto any attempts to raise taxes. President Bush’s pledge did not last through his second year in office. In a budget summit with key leaders of the Democrat-led Congress, President Bush announced his willingness to support a tax increase as part of a fiscal deficit reduction agreement. The resultant budget plan made deep cuts in national defense expenditures and token cuts in domestic expenditures, in addition to major tax increases. Democrats cheered the return to a more progressive tax rate structure. These Democrats ridiculed as trick-down economics the arguments by supply-side theorists that high marginal tax rates would impede economic growth.

President Bill Clinton’s plan to reduce fiscal deficits centered on key tax increases on upper-income Americans. Specifically, President Clinton successfully convinced a Democrat-led Congress to add 2 new top marginal tax rates of 36% and 39.6%. The Clinton administration further raised the corporate income tax from 34% to 35%. But the interest groups retained virtually all of their deductions, exemptions, and special treatments under the new tax regime. Key special interest groups targeted specific tax breaks for the elderly, education, child care, home ownership, investment income, or a wide variety of other industries. These tax breaks would receive strong special interest group support. In contrast, broad-brush tax reductions would not inspire the same kind of interest group enthusiasm in the common form of election campaign contributions to particular Congress members. Cynics might argue that politicians would deliberately enact high tax rates in order to inspire interest groups to seek new special protections by making campaign contributions for the comfort of lawmakers.

President George W. Bush came into office and then vowed not to make the same mistake as his father. President Bush strongly committed to reducing income taxes and believed that tax credits would help revive the economy. He believed that fiscal deficits were the result of slow economic growth. Tax reductions might temporarily add to fiscal deficits, but eventually better economic growth would increase tax revenues to help eliminate fiscal deficits.

In 2 separate tax-cut economic stimulus packages in 2001 and 2003, President Bush moved the Republican-led Congress to reduce the top marginal tax rate from 39.6% to 35%. Under this new tax regime, corporate stock dividends would be subject to the much lower 15% tax rate rather than the same top rates for wages and bonuses. Almost one-half of all American families owned stocks or mutual funds at the time, and this new tax break would be politically popular. Under the Bush administration, the tax laws made the standard personal deduction for couples twice the deduction for a single person. This change corrected the prior marriage penalty or a flaw in the tax code that had long plagued couples who filed joint tax returns. In addition, the Bush administration raised the tax credit for child care from $600 to $1,000. In fact, this change was politically popular with bipartisan support by many Democrats as well as Republicans. Finally, the Bush tax package chipped away again at the basic tax on capital gains (profits from the sale of investments held at least one year). The Bush administration reduced this tax from 20% to 15%, or a new tax rate that was much lower than half of the top marginal tax rate of 35% on wages and bonuses.

The Republican-led House and Senate approved the Bush tax package on largely party line votes. Most Democrats opposed the Bush tax package and so argued that this tax package primarily benefited the rich with little stimulus for the economy. Most importantly, the Bush tax cuts would add to the already growing annual fiscal deficits. Republicans argued that the Bush tax package benefited all U.S. taxpayers insofar as the rich paid more than 70% of the U.S. income taxes with some beneficial tax reductions. However, these Bush tax reductions would not have caused new major economic growth as the U.S. economy experienced the subprime U.S. mortgage credit crunch and Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 toward the end of the Bush administration.

President Barack Obama campaigned on a promise to reduce taxes on the middle class of 95% of U.S. taxpayers. He also pledged to raise taxes on upper-income Americans, or U.S. families with $250,000 household income or more each year. This combination of changes in U.S. taxation would make the tax code more progressive.

In the Obama economic stimulus package of 2009, a major item was Making Work Pay: tax payments of $400 to U.S. workers with income under $75,000, and tax payments of $800 to U.S. workers with income under $150,000. Any workers who paid the Social Security payroll taxes would receive these tax credits. In fact, President Obama argued that these tax credits would partially offset the Social Security payroll tax. Later, Congress made these tax credits permanent. President Obama urged Congress to allow the Bush tax cuts to expire. This tax cut expiration would raise the top marginal tax rate from 35% to 39.6%. Americans generally believe in the merits of progressive income taxation: higher-income people can afford to pay larger percentages of their income in taxes (than lower-income people in America). However, deliberate attempts by government to use the tax code to equalize income violates traditional American notions of social fairness.

President Barack Obama recommended an increase in the capital gains tax rate from 15% to 20%. This tax change would still leave a significant tax preference for capital gains (profits from the sale of stocks, bonds, and real estate investments). In America, capital gains would be subject to a tax rate approximately half of the top marginal tax rate on wages and bonuses. In recent times, some economists such as Emmanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty argue that the differential tax treatments of wages versus capital gains might have contributed to larger disparities in both wealth and income in America and other rich countries. To the extent that the rich would attract more capital gains than wages and bonuses, sharper inequality would arise from the continuation of different tax treatments for various income categories (wages and bonuses versus capital gains). For this reason, progressive lawmakers such as Senator Elizabeth Warren and her Democratic colleagues would subsequently argue for a wealth tax on the rich to better balance wealth and income disparities in America. Nevertheless, special interest politics would make comprehensive tax reform an unlikely prospect for America. The subsequent Trump and Biden administrations would make incremental tax regime changes in response to the long prevalent special interests and ideological differences.

Modern tax policy pluralism praises the virtues of an interest group system. In this system, public policy represents the equilibrium in the group struggle and the best approximation of the public interest. However, it is clear that special interest groups often put broad segments of the American public at a disadvantage. Tax laws treat different types of income differently. These different tax laws penalize work and investment and so divert capital investment into non-productive tax shelters and an illegal underground economy. The social unfairness and inefficiency of complex tax laws emerge from special interest groups. Political considerations sometimes may or may not adequately reflect these special interests in tax policy pluralism. Incremental U.S. tax regime changes often serve as a natural response to the long prevalent special interests and ideological differences.

The new classic Sargent-Wallace unpleasant monetarist arithmetic analysis demonstrates that the central bank often cannot contain money supply growth, or high inflation, if the fiscal authority engages in endless government bond issuance to fund public investment projects for better economic growth and employment. In this case, the central bank temporarily loses its monetary policy independence due to a lack of fiscal prudence. As a net result, the central bank would eventually tolerate much higher inflation sooner or later as money supply growth (inflation) accelerates due to the gradual accumulation of fiscal deficits on the top of national debt. In effect, national debt caps would probably help constrain the positive fruits of macro policy coordination between the central bank and the fiscal authority.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh (online brief biography)

Co-Chair

AYA fintech network platform

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2017-08-13 09:36:00 Sunday ET

Several investors and billionaires such as George Soros, Warren Buffett, Carl Icahn, and Howard Marks suggest that the time may be ripe for a major financia

2017-04-25 06:35:00 Tuesday ET

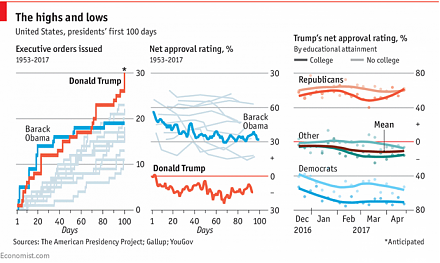

This nice and clear infographic visualization helps us better decipher the main memes and themes of President Donald Trump's first 100 days in office.

2017-03-21 09:37:00 Tuesday ET

Trump and Xi meet in the most important summit on earth this year. Trump has promised to retaliate against China's currency misalignment, steel trade

2019-02-21 12:37:00 Thursday ET

Apple shakes up senior leadership to initiate a new transition from iPhone revenue reliance to media and software services. These changes include the key pr

2020-04-24 11:33:00 Friday ET

Disruptive innovations tend to contribute to business success in new blue-ocean markets after iterative continuous improvements. Clayton Christensen and

2018-09-21 09:41:00 Friday ET

Former World Bank and IMF chief advisor Anne Krueger explains why the Trump administration's current tariff tactics undermine the multilateral global tr