2023-07-28 11:28:00 Fri ET

stock market competition macrofinance stock return s&p 500 financial crisis financial deregulation bank oligarchy systemic risk asset market stabilization asset price fluctuations regulation capital financial stability dodd-frank andrei shelifer lucian bebchuk

Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried (2006)

Pay without performance: the empty promise of executive compensation

Harvard Law School corporate governance professors Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried criticize the standard view of executive pay that senior executive managers negotiate incentive compensation contracts with shareholders in accordance with shareholder wealth maximization. In stark contrast, Bebchuk and Fried argue that executive compensation seems to be more consistent with senior executive control of board approval subject to some outrage constraints. Bebchuk and Fried provide empirical evidence in support of this alternative viewpoint. In fact, senior executive managers often choose to camouflage incentive pay negotiations subject to major board oversight. From a positive perspective, much of the evidence on camouflage and managerial control of risk is quite persuasive. From a normative perspective, corporate governance reforms can dramatically improve executive pay systems in pursuit of better overall corporate performance. Overall, Bebchuk and Fried strive to connect the dots between executive pay and corporate stock return performance through their empirical study of performance pay sensitivity in Corporate America. The rather low performance pay sensitivity calls for corporate governance reforms. There can be different ways for economists and politicians to skin the cat, and all roads eventually lead to Rome. However, no one can build Rome in one day.

Bebchuk and Fried show that corporate boards have persistently failed to negotiate incentive pay contracts with senior executive managers under board oversight and supervision. Their in-depth empirical study of incentive pay practices such as stock option plans, cash dividends, and retirement benefits have mysteriously decoupled executive compensation from corporate stock return and operational performance. Senior executive managers can devise board mechanisms to camouflage both the dollar amount and performance insensitivity of executive pay. Managerial control and influence over executive pay can erode shareholder wealth due to increases in executive pay as well as some rare unique pay practices. These practices often dilute and distort managerial incentives away from shareholder value maximization. Bebchuk and Fried identify the basic problems with the current reliance on boards as the guardians of shareholder interests. In addition to independent directorships, boards should be made more dependent on shareholders with few arrangements that may inadvertently insulate both directors and senior executive managers from shareholder dismissal in the presence of managerial control and entrenchment. As Bebchuk and Fried suggest, the removal of special arrangements for managerial entrenchment can help enhance corporate governance, stock return performance, and operational efficiency in due course.

The fundamental economic welfare theorems suggest that business organizations often seek to maximize profits with efficient business decisions in the best interests of shareholders. In the classic principal-agent view of executive compensation, the long prevalent corporate governance arrangements can often help promote better economic growth and sustainable development in the modern democratic capitalist society when the dominant business form is the public corporation. An ideal model of corporate governance would involve senior executive managers whose interests accord with shareholder wealth maximization. However, information asymmetries and team coordination problems prevent most shareholders from close operational engagement in core business decisions such as mergers and acquisitions, capital investment expenditures, research and development innovations, capital structure choices, cash management schemes, and corporate payout policies etc. For these reasons, most shareholders often need to rely on the board of directors to oversee business judgment made by senior executive managers. So board representation serves as the major mechanism for corporate control, ownership, and governance. Because it is infeasible for shareholders to agree on all major business decisions, these shareholders delegate decision rights to senior executive managers through the careful selection of board members. These members, specifically independent directors, oversee and supervise business decisions and operations in accordance with shareholder wealth maximization. Principal-agent theory helps design optimal incentive pay contracts for senior executive managers to serve in the best interests of shareholders subject to board approval and oversight.

The principal-agent theory presumes that most incentive pay contracts often serve as an optimal response to the corporate climate. However, many CEOs and other senior executive managers have a great deal of control over their boards, and thus over their own pay decisions. An alternative approach to the principal-agent theory involves explicitly recognizing that the incentive pay contracts between CEOs and their corporations are not the same pay contracts that would occur if CEOs tried to bargain at arms-length with shareholders in pursuit of profit maximization. Senior executive managers often tend to extract enormous sums of money (or economic rent) through their control of core business decisions such as executive pay pacts and other private benefits of control.

Bebchuk and Fried adopt this alternative view of executive compensation due to both managerial power and rent extraction. Bebchuk and Fried delve into empirical evidence in support of the central hypothesis that executive pay practices cannot explain suboptimal core business decisions in accordance with shareholder wealth maximization. In Corporate America, CEOs can effectively set their own pay pacts subject to some outrage constraints by the market. These outrage constraints arise from the public reaction to extremely high CEO pay. To the extent that CEOs often have great sway over their own pay, the Bebchuk-Fried evidence often helps better understand executive compensation through this lens (instead of a principal-agent contract where shareholders can capture all the economic rent). CEOs and other senior executive managers often steer core business decisions such as executive pay contracts and other private benefits to the detriment of minority shareholders and sometimes even outside blockholders. On balance, managerial entrenchment and rent extraction better explain the Bebchuk-Fried evidence of low performance pay sensitivity in Corporate America.

In the classical principal-agent problem, the principal must delegate core business decisions to his or her agent whose incentives may or may not perfectly align with the best interests of the principal. A partial solution to this principal-agent problem is to apply incentive pay contracts that induce the agent to perform better business missions. Executive pay is a real-world example of a principal-agent problem since the shareholders (the principal) delegate virtually all core business decisions to the CEO and other senior executive managers (the agent). Incentive pay contracts so serve as a partial solution to this classical principal-agent problem in law, finance, and specifically corporate governance.

Optimal pay contracts can serve as a partial solution to the agency problem in most industrial business organizations. Even though most economists acknowledge that many important markets are indeed oligopolies of some sort, most of the economic models focus on perfectly competitive markets. Economists can apply the Bellman equation and recursive mathematical tools to solve the Euler first-order conditions for competitive equilibrium results in these complete and perfect markets.

Bebchuk and Fried challenge the presumption that arms-length optimal pay pacts represent the right way for CEOs and other senior executive managers to describe executive pay practices. In fact, the shareholders cannot contract with CEOs and other senior executive managers. Instead, the shareholders can only contract with most senior executive managers indirectly through the board of directors. Directors therefore act as an intermediary between shareholders and managers. Unless the board acts perfectly in the best interests of shareholders, executive pay contracts can differ substantially from those pay pacts that the optimal principal-agent model predicts in theory. In practice, many issues distort board preferences far away from the classic goal of shareholder wealth maximization. The CEO and other executive managers can capture the board of directors (who may or may not act in the best interests of minority shareholders). The incentive pay contracts between the CEO and the board are not likely to be the pay schemes that contribute to shareholder wealth maximization subject to the usual constraints in the principal-agent problem. Rather, the incentive pay contracts tend to reflect optimal economic rent extraction by the CEO and other senior executive managers.

Several reasons can help explain why the board is likely to consider CEO interests rather than shareholder interests. First, directors have incentives to keep their jobs. Directors make good money and sometimes receive substantial perks and private benefits of corporate control. Opposing CEO interests substantially increases the rare likelihood that top executive managers may not re-nominate defiant directors to the board. As a result, these defiant directors would lose these private benefits of corporate control. Second, the CEO and other senior executive managers can provide fresh benefits to directors in many ways. Bebchuk and Fried provide many cases where directors can receive substantial business opportunities for the CEO. Some CEOs can direct corporate investments and charitable contributions toward the relevant business organizations that some directors favor in fundamental ways. Third, some CEOs can apply influence on the corporations on whose boards these CEOs serve to help their directors acquire additional lucrative directorships. From this fundamental viewpoint, there are substantive reasons why most directors have incentives to cater to the wishes and interests of the CEO and executive managers. It is therefore unrealistic for most economists to expect the board to negotiate the best possible executive pay contracts in the best interests of minority shareholders. Shareholders sometimes sue the board, vote down managerial stock option plans, and put forward their own proposals. However, unless the shareholders hold large equity stakes and so acquire new seats on the board, these measures are unlikely to cause meaningful changes in core business decisions and executive behaviors. As Bebchuk and Fried suggest, none of the capital market forces and competitive product market threats are sufficiently powerful to push directorships and executive compensation practices toward the equilibrium pay schemes in the optimal agency theory. Bebchuk and Fried thus analyze and delve into the alternative managerial power view of executive compensation in Corporate America.

Bebchuk and Fried present an alternative approach to executive pay on the basis of managerial power inside the corporation. From time to time, the CEO has a good deal of control over the board, and this control includes the power to set part of his or her own executive compensation. Outrage costs occur when both directors and senior executive managers bear costs from negative public responses to extremely high executive compensation. The main difference between the managerial-power and principal-agent stories is stark: The level of pay in the principal-agent approach is set so that the CEO receives at least his own reservation utility. In contrast, the level of pay in the managerial power story often tends to be set as high as possible, and the upper bound on pay due to broader public perceptions. The Bebchuk-Fried managerial power story differs substantially from the principal-agent predictions of clear incentive pay practices in accordance with shareholder wealth maximization. Stock options and other incentive pay practices can help justify high executive pay at a minimum of public outrage.

The observable incentive pay packages often cannot filter out fundamental factors that affect performance well beyond managerial control. Stock options are almost always a function of raw stock returns, so that during a stock market upturn, senior executive managers generally receive large returns from their stock options due to the market-wide systematic component of stock returns. Specifically, some public corporations can strategically reduce the strike prices on executive stock options. This common pay practice can be highly valuable when the stock options are out of the money. As senior executive managers can exercise their stock options when these call options substantially move in the money, these executive managers can receive large cash windfalls during a usual economic boom. Most senior executive managers structure their incentive pay packages so that these managers can often unwind meaningful incentives in executive pay programs. This pervasive practice helps explain the rather low performance pay sensitivity in Corporate America.

Although senior executive managers can have some leeway to gain liquidity on at least some of their stock options, Bebchuk and Fried argue that the quantity of key stock options sold can suggest that several incentive pay packages cannot provide as many incentives as one might suppose. Many senior executive managers have been able to hedge their stock options with collars. These collars are key derivative combinations that help lock in current stock price gains with no or few meaningful incentives in executive option pay programs. Overall, Bebchuk and Fried contend that the financial freedom for most senior executive managers to unwind incentives in stock option pay programs seems large enough. In this common unique fashion, incentive option pay programs are set up to transfer economic rents instead of real economic incentives for better executive performance.

Many executive pay practices are hidden. Bebchuk and Fried refer to this practice as camouflage. When senior executive managers set up their own CEO pay plans subject to some outrage constraints, these managers try to be careful to structure these executive pay programs in order to minimize outrage. From time to time, key CEOs and other senior executive managers camouflage executive compensation in the rare forms that most people cannot disclose in the press. For instance, senior executive managers typically receive supplemental retirement plans (SERPs) that go well beyond the retirement plans given to most employees. Many corporations cannot deduct the SERPs from corporate income taxes, so these funds are not tax efficient solutions to executive compensation. However, these retirement plans are a good way for senior executive managers to camouflage their private benefits of control over core business decisions. In most cases, these retirement plans do not show up in press reports of executive compensation. Most corporations sometimes allow senior executive managers (but not other employees) to defer compensation until retirement. This special treatment guarantees some optimal rate of return well in excess of several market rates. From GE to Enron, the optimal rate of return on executive retirement is 12% annual return. The present value of this return can be quite substantial, but sufficiently hidden that this return almost never enters press reports of executive compensation. Senior executive managers often extract rents in many other forms such as health care benefits, corporate jets, cars, apartments, security systems, business loans, and some other private benefits of control.

Bebchuk and Fried present empirical evidence in support of camouflage in several executive pay practices. The high level of camouflage in executive pay shows that both boards and senior executive managers wish to hide true compensation from the public. Optimal incentive pay contracts offer no good reasons why corporations would wish to hide executive compensation from press reports. The Bebchuk-Fried managerial power explanations provide good reasons for the pervasive executive pay practices in Corporate America. From their prescient and in-depth econometric analysis, Bebchuk and Fried find that executive pay often cannot help explain the subpar stock return and operational performance of most U.S. public corporations. The low executive performance pay sensitivity remains open to controversy.

As Bebchuk and Fried suggest, executive compensation turns out to be inefficient and excessive relative to some theoretical stock market benchmark. A realistic set of corporate governance reforms can probably help transform the status quo into a better equilibrium steady state. As senior executive managers effectively set their own pay subject to some outrage constraints, shareholders would be better off by trying to bargain new incentive pay practices with these senior executive managers through some direct corporate governance mechanism. Regulatory improvements can require setting up some new executive compensation oversight committee on the board of directors. The dual representation of both minority shareholders and independent directors suffices to help shareholders vote on arms-length executive pay negotiations. Bebchuk and Fried further encourage investors to pay executive stock options that filter out general market or industry movements. This filter helps make it difficult for senior executive managers to unwind incentives for better CEO performance. Moreover, Bebchuk and Fried encourage both regulators and market participants to make the structure of executive pay more transparent with granular and regular press reports. In another relevant strand of literature, Bebchuk and his co-authors argue that corporate governance reforms should focus on shareholder empowerment. Such reforms should empower shareholders to nominate their own representative candidates to independent directorships and important committees on the board of directors. For instance, several tech titans such as Apple, Amazon, Facebook, Google, Microsoft, Nvidia, SpaceX, and Tesla develop new committees and independent directorships for better data governance and privacy protection. As Bebchuk and Fried suggest, perhaps managerial control and influence over the board, and ultimately over their own executive compensation, can be an inevitable result of the Berle-Means (1932) public corporation with diffuse stock ownership.

Harvard Law School corporate governance professors Lucian Bebchuk and Jesse Fried criticize the standard view of executive pay that senior executive managers negotiate incentive compensation contracts with shareholders in accordance with shareholder wealth maximization. In stark contrast, Bebchuk and Fried argue that executive compensation seems to be more consistent with senior executive control of board approval subject to some outrage constraints. Bebchuk and Fried provide empirical evidence in support of this alternative viewpoint. In fact, senior executive managers often choose to camouflage incentive pay negotiations subject to major board oversight. From a positive perspective, much of the evidence on camouflage and managerial control of risk is quite persuasive. From a normative perspective, corporate governance reforms can dramatically improve executive pay systems in pursuit of better overall corporate performance. Overall, Bebchuk and Fried strive to connect the dots between executive pay and corporate stock return performance through their empirical study of performance pay sensitivity in Corporate America. The rather low performance pay sensitivity calls for corporate governance reforms. There can be different ways for economists and politicians to skin the cat, and all roads eventually lead to Rome. However, no one can build Rome in one day.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2018-01-15 07:35:00 Monday ET

Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin welcomes a weak U.S. dollar amid pervasive fears of an open trade war between America and China. At the World Economic For

2017-10-09 09:34:00 Monday ET

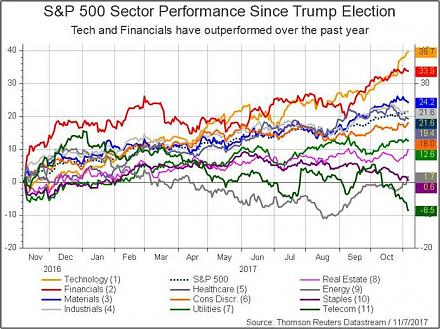

The current Trump stock market rally has been impressive from November 2016 to October 2017. S&P 500 has risen by 21.1% since the 2016 presidential elec

2017-06-15 07:32:00 Thursday ET

President Donald Trump has discussed with the CEOs of large multinational corporations such as Apple, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon. This discussion include

2022-05-05 09:34:00 Thursday ET

Corporate payout management This corporate payout literature review rests on the recent survey article by Farre-Mensa, Michaely, and Schmalz (2014). Out

2025-10-03 10:31:00 Friday ET

Stock Synopsis: With a new Python program, we use, adapt, apply, and leverage each of the mainstream Gemini Gen AI models to conduct this comprehensive fund

2019-11-23 08:33:00 Saturday ET

MIT financial economist Simon Johnson rethinks capitalism with better key market incentives. Johnson refers to the recent Business Roundtable CEO statement