2023-12-05 09:25:00 Tue ET

stock market trust managerial entrenchment corporate governance rent protection stock ownership asset management business judgment investment legal protection investor protection asset specificity berle-means stock ownership dispersion

Abstract

We design a model of corporate ownership and control to assess Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse incumbent stock ownership. Berle-Means convergence occurs when legal institutions for investor protection outweigh in relative importance the firm-specific protection of shareholder rights. While these arrangements are complementary sources of investor protection, Berle-Means convergence draws the corporate outcome to the socially optimal quality of corporate governance. High ownership concentration creates perverse incentives for inside blockholders to steer major business decisions to the detriment of both minority shareholders and outside blockholders. Our analysis sheds skeptical light on high insider stock ownership with managerial entrenchment and rent protection.

Keywords: dynamic convergence of Berle-Means incumbent stock ownership dispersion; law and finance; corporate governance; investor protection; managerial entrenchment; rent protection.

Research Question/Issue: This study provides a new mathematical analysis of the non-linear relation between stock ownership dispersion and legal protection of investor rights. This analysis shines new light on whether international divergence from wide stock ownership dispersion serves as a (sub)optimal corporate outcome.

Research Findings/Insights: We design a model of corporate ownership and control to assess Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse incumbent stock ownership. This convergence occurs when legal institutions for investor protection outweigh in relative importance the firm-specific protection of shareholder rights. While these arrangements are complementary sources of investor protection, Berle-Means convergence draws the corporate outcome to the socially optimal quality of corporate governance. High ownership concentration creates perverse incentives for inside blockholders to steer major business decisions to the detriment of both minority shareholders and outside blockholders. This analysis sheds skeptical light on high insider stock ownership with managerial entrenchment and rent protection.

Theoretical/Academic Implications: This study offers a new mathematical model of the dynamic evolution of both corporate ownership and governance structures over time. This model is general enough to encapsulate both arguments for and against Berle-Means convergence as special cases. In the context of equilibrium interplay between inside blockholders and minority shareholders, the model predicts that the former obtain a positive rent from their large blocks of stock by steering major corporate decisions at the expense of both minority shareholders and outside blockholders (while the latter maintain a neutral utility threshold). Insofar as incumbents seek and secure economic rent in the corporate game, this equilibrium interplay persists as a deviation from the social optimum. Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse incumbent stock ownership may or may not materialize due to the unilateral tilt of both legal and firm-specific asset arrangements for investor protection. These analytical results contradict Leland and Pyle’s (1977) central thesis that incumbent stock ownership sends a positive signal of firm-specific investment project quality as a natural response to information asymmetries between corporate insiders and minority shareholders. To the extent that both firm value and incumbent ownership vary together endogenously, this common simultaneity leads to an ambiguous empirical nexus after one adequately controls for a unique array of exogenous productivity parameters (Coles, Lemmon, and Meschke, 2012).

Practitioner/Policy Implications: High incumbent stock ownership may create perverse incentives for corporate insiders to steer major business decisions to the detriment of both minority shareholders and outside blockholders. For this reason, the unique set of best practices in corporate governance should include competitive forces that lead to Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse stock ownership. These forces help prevent managerial entrenchment and rent protection within each corporation.

Adolf Berle and Gardiner Means’s (1932) seminal work serves as the canonical qualitative basis for the separation of corporate ownership and control. Their primary thesis has set the mainstream foundation of corporate governance research for legal scholars, practitioners, and economists over 90 years. In line with this Berle-Means thesis, corporate control over physical assets responds to a centripetal force and concentrates in the hands of only a few incumbents, whereas, corporate ownership is centrifugal, splits into small units, and passes from one person to another (Berle and Means, 1932: 9). In the Berle-Means image of the modern corporation, executives and directors gain their income primarily from the effort that these incumbents put into business decisions, but not from the return on their stock investment in the enterprise. To the extent that corporate structures evolve in response to competitive pressures in the capital markets, the Berle-Means thesis predicts gradual convergence toward diffuse equity ownership as the most efficient form.

In this paper, we design and develop a model of corporate ownership and control to assess the theoretical plausibility of Berle-Means convergence toward dispersed incumbent stock ownership. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first mathematical analysis of whether Berle-Means convergence is optimal. Further, this analysis delves into whether Berle-Means convergence is desirable from the social planner’s perspective. A subsequent analysis explores the equilibrium interplay between inside blockholders and minority shareholders.

The core analytical results suggest that Berle-Means convergence occurs when legal institutions for investor protection outweigh in relative importance firm-specific asset protection of investor rights. While legal and firm-specific asset arrangements are complementary sources of investor protection, Berle-Means convergence toward dispersed incumbent stock ownership draws the corporate outcome to the socially optimal quality of corporate governance. High incumbent stock ownership creates perverse incentives for inside blockholders to steer corporate decisions to the detriment of minority shareholders.

In the current study, we extend and generalize Yeh, Lim, and Vos’s (2007) baseline model of Berle-Means convergence with the constant elasticity of substitution (CES) production function in comparison to the Cobb-Douglas special case. While the first proposition remains the same in this more general CES production function, several new analytical results include institutional complementarities, socially optimal incumbent equity ownership stakes, and persistent deviations from Berle-Means stock ownership dispersion in equilibrium. The latter result is an equilibrium subpar outcome in the corporate game with information asymmetries between inside blockholders and minority shareholders. These novel propositions serve as the theoretical basis for subsequent empirical analysis. The appendices provide the complete mathematical derivation.

Our analysis rests on the fundamental concept that corporate insiders can often steer key business decisions at the detriment of minority shareholders. The corporate governance literature is replete with examples of deliberate use of managerial power that leads to a deterioration in firm value. For instance, incumbents may engage in earnings management prior to major corporate events such as initial public offerings (Teoh, Welch, and Wong, 1998a), seasoned equity offerings (Teoh, Welch, and Wong, 1998b), stock-for-stock mergers (Erickson and Wang, 1999; Louis, 2004), and open-market repurchases (Gong, Louis, and Sun, 2008). Also, corporate managers tend to opportunistically time the stock market through equity issuance when the firm’s market value is high relative to its book value or past market values (e.g. Jung, Kim, and Stulz, 1996; Pagano, Panetta, and Zingales, 1998; Baker and Wurgler, 2002; Huang and Ritter, 2009). In addition, abnormal stock returns tend to arise as a result of corporate events that are associated with asset expansion or contraction (e.g. Loughran and Ritter (1995), Ikenberry, Lakonishok, and Vermaelen (1995), Loughran and Vijh (1997), Titman, Wei, and Xie (2004), Anderson and Garcia-Feijoo (2006), Fama and French (2006), and Cooper, Gulen, and Schill (2008)). Incumbent blocks of stock further facilitate this managerial rent-protection mechanism that drives business decisions to benefit inside blockholders (e.g. Bebchuk, 1999; Bebchuk and Roe; 1999; Dyck and Zingales, 2004). In this context, the desire for retaining private benefits of control may induce incumbents to introduce corporate arrangements such as poison pills and board classifications to insulate directors and executives from the influence of outside blockholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Bebchuk, Coates, and Subramanian, 2002; Bebchuk and Cohen, 2005; Bebchuk and Kamar, 2010; Bebchuk and Jackson, 2012; Bebchuk, 2013; Bebchuk, Brav, and Jiang, 2015). In summary, both managerial power and entrenchment are essential ingredients in our analysis of the equilibrium interplay between inside blockholders and minority shareholders. This interplay can shed light on whether the Berle-Means image of the modern corporation is sustainable near the social optimum.

This study provides a theoretical model of the dynamic evolution of corporate ownership and governance structures over time. This model is general enough to encapsulate both arguments for and against Berle-Means convergence as special cases. In the context of equilibrium interplay between inside blockholders and minority shareholders, the model predicts that the former obtain a positive rent from their large blocks of stock by having both corporate power and influence to steer business decisions while the latter maintain a neutral utility threshold. Insofar as incumbents seek and secure economic rent in the corporate game, this equilibrium interplay persists as a non-trivial deviation from the social optimum. Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse incumbent stock ownership hence may or may not materialize due to the unilateral tilt of both legal and firm-specific asset arrangements for investor protection. In summary, our mathematical analysis sheds skeptical light on high insider stock ownership with managerial entrenchment and rent protection.

Literature review

In this section, we review the relevant literature on Berle-Means convergence toward dispersed incumbent stock ownership. The Berle-Means thesis suggests that the inexorable separation of corporate ownership and control leads to a conflict of interest between incumbents and shareholders (Berle and Means, 1932; Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Fama and Jensen, 1983, 1985). As businesses grow in size and complexity and shareholders increase in number, incumbent stock ownership becomes proportionally smaller. Both corporate executives and directors derive income largely from the returns on their effort as incumbents, not from their equity investment in the corporation. As a result, the gradual dilution of incumbent equity ownership suggests a unique form of Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse stock ownership.

The literature provides polemic and divergent views of Berle-Means convergence. On the one hand, the neoclassical convergence hypothesis suggests that Berle-Means convergence arises as a natural result of competitive pressures in seeking to reduce agency costs and managerial slack. On the other hand, there are path-dependent forces that prohibit Berle-Means convergence. The reasons for this path-dependency include politics, managerial rent protection, asset specificity, and social norms of fairness and trust. For the practical purposes of this study, we attempt to encapsulate both sides of the debate in a simple model of corporate ownership concentration. This analysis motivates several testable hypotheses for subsequent empirical research and in turn has pivotal policy implications for corporate governance.

A prominent strand of literature suggests that most common-law countries outperform civil-law countries in promoting an amicable environment for financial markets to prosper in terms of market valuation (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1997, 1998, 1999, 2002; Demirguc-Kunt and Maksimovic, 1998; Acemoglu and Johnson, 2005; La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer, 2006, 2008). Also, several studies find evidence in support of a positive relationship between stock market development and several broad measures of economic growth (Levine and Zervos, 1998; Bekaert, Harvey, and Lundblad, 2005; Brown, Martinsson, and Petersen, 2013). The U.S., the U.K., and most other OECD countries with Berle-Means corporations represent a lion’s share of the value of the global stock market. In these economies, shareholders delegate the monitoring role to directors. Effective directorship imposes limits on self-interested managers’ attempts to divert corporate resources in a way that erodes shareholder value. This mechanism allows investors to rely upon directors’ judgment in monitoring management. In turn, the close alignment of shareholder and director interests helps reduce agency costs in pursuit of shareholder wealth maximization (Fama, 1980; Demsetz, 1983; Easterbrook and Fischel, 1991). Just as the founders of a corporation have incentives to employ state-of-the-art technology or efficient means of production, incumbents face incentives to build the ownership and governance structures that investors prefer. There can be an optimal nexus of contracts between incumbents and shareholders when directors and managers receive compensation in the form of stock-based pay (Jensen and Meckling, 1976; Jensen, 1986). This kind of executive compensation helps resolve the inherent conflict of interest between shareholders and incumbents. In this view, incumbents serve in the best interests of shareholders most of the time to receive better prices for corporate securities. Better investor protection encourages accurate stock price discovery, efficient corporate investment, and better access to external finance (McLean, Zhang, and Zhao, 2012). Competitive forces and market dynamics result in the natural selection of corporate arrangements in a Darwinian evolution. This dynamic characterization suggests that corporate ownership and governance structures should gravitate toward the most efficient form.

Since investors provide capital to corporations and delegate managerial power to incumbents, insofar as there are sound legal institutions that effectively protect shareholder rights, the primary role of investors is to offer liquidity to corporations. By holding small equity stakes, investors and some incumbents inject capital into more corporations and as a result reap risk-sharing benefits (Fama and Jensen, 1983, 1985; Coffee, 1991, 2001). Because shareholders can discipline management via a variety of corporate control mechanisms, dispersed stock ownership for both investors and incumbents is likely to survive the test of time in the stock-market-oriented model.

The stock-market-oriented model creates a positive externality to investors and corporations. Investors spread their equity stakes across a portfolio of industries or corporations to reap diversification benefits. Corporations use equity and some other sources of funds to implement their valuable investment projects. Both parties are better off and experience a Pareto improvement. Further, there is an inevitable trade-off between liquidity and control (Coffee, 1991; Maug, 1998). Investors may voluntarily choose to forego their control over management and then retain the option to liquidate diffuse shares. Insofar as investors hold well-diversified stock portfolios, any specific loss can be offset by higher returns on other individual stocks for the median investor to perform well. Most investors’ preference for liquid equity stakes in turn leaves the effective monitoring role to directors. This preference for liquidity results in the rise of diffuse stock ownership for incumbents and minority shareholders (Coffee, 2001). Berle-Means convergence to greater stock ownership dispersion can be viewed as a step toward the efficient ownership structure.

The increasing globalization of financial markets is often viewed as another competitive force that drives convergence to the Berle-Means image of the modern corporation. Multinational corporations attempt to attain global scale to opt into high-quality regimes of securities regulation. The U.S. and U.K. landscapes are examples of regimes that enhance both transparency and fiduciary protection (Coffee, 1999, 2002). A key feature of the stock-market-oriented model is its adaptability to systemic changes. Deep and liquid stock markets that emphasize shareholder interests facilitate timely responses during a period of financial stress (Cunningham, 1999). These strong and responsive stock markets serve as an external monitor in the form of ubiquitous analyst forecasts or cross-border mergers and acquisitions (Gordon, 1999). Also, self-regulation can arise from a desire to emulate a set of best practices in corporate governance because many OECD countries with Berle-Means corporations have performed well in comparison to their East Asian and continental European counterparts, the latter of which deviate from the stock-market-oriented model (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1999; Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000). In addition, the recent evidence suggests that many non-U.S. corporations choose to cross-list on the U.S. stock exchanges to subject management to stricter disclosure requirements and governance standards in a way that reduces private benefits of control (Reese and Weisbach, 2002). In summary, the global trend of systemic adaptation and emulation represents another route for Berle-Means convergence toward diffuse fractional stock ownership.

Politics can confine the terrain on which the large enterprise may evolve (Roe, 1991, 2000). This confinement subsequently shapes the efficient form of corporate ownership to which the large enterprise adapts. Also, this confinement gives rise to specific power-sharing arrangements. For instance, U.S. populism suggests that no institution should have significant financial power (Lipset and Schneider, 1987; Roe, 1991; Acemoglu, Johnson, and Robinson 2001; Johnson and Kwak, 2010). This pervasive belief can be the root cause of anti-bank sentiment in America (Johnson and Kwak, 2010; Admati and Hellwig, 2012). The mistrust of financial power may have contributed to the unequivocal case for laws that limit financial institutions’ stock ownership (Black, 1990; Roe, 1991; Coffee, 1991, 1999, 2001, 2002). To satisfy the large corporation’s capital needs, fractional shares arise as a solution. This fragmentation of equity stakes promotes a shift in corporate power from financial institutions to incumbents (Roe, 1993, 1994). In turn, politics shapes the prevalent ownership structure, and this ownership structure affects the internal power-sharing arrangements in the corporate context. The Berle-Means separation of ownership and control is thus a natural reality in American corporations (Roe, 1998: 217, 241).

In Japan and Germany, however, investors are much more tolerant of financial institutions’ involvement in corporate affairs (Roe, 1993: 1936). Many of these financial institutions hold large blocks of stock to exert control and influence over management. Authority seems to be shared among incumbents and large shareholders in German and Japanese corporations (Roe, 1993: 1941-1946). The blockholder mechanism in Japan and Germany differs significantly from the U.S. Berle-Means image of the modern corporation. In light of the structural differences, the political theory of corporate finance implies a schematic process. Politics sets the asymptotes of financial institutions’ reach in stock ownership. These asymptotes impart the conditions for the separation of ownership and control. Thereby, political forces help shape corporate ownership and governance practices. To the extent that these forces appear to persist over time, complete Berle-Means convergence in corporate structures may not come to reality.

The size of private benefits of control plays a role in the determination of corporate ownership structure. Private benefits of control are those benefits that accrue to incumbents, who have effective control of the corporation, but not to minority shareholders (Reese and Weisbach, 2002). Examples include business connections, large office suites, corporate jets, executive retreats, and many other perquisites. Leaving corporate control up for grabs may attract attempts to acquire the company by rivals who seek to capture private benefits of control (Bebchuk, 1999). This phenomenon is more pronounced when private benefits of control are large. In these circumstances, incumbents may keep a lock on control by choosing to hold concentrated equity stakes (Bebchuk, 1999: 1-2; Dyck and Zingales, 2004). This concentrated ownership structure then serves as an antidote to potential takeover bids. In addition, the desire for keeping private benefits of corporate control may induce incumbents to introduce corporate arrangements such as poison pills and board classifications to insulate directors and executives from the direct influence of outside blockholders (Shleifer and Vishny, 1986; Bebchuk, Coates, and Subramanian, 2002; Bebchuk and Cohen, 2005; Bebchuk and Kamar, 2010; Bebchuk and Jackson, 2012; Bebchuk, 2013; Bebchuk et al, 2015).

According to the rent-protection theory, concentrated ownership tends to prevail in corporate regimes where private benefits of control are large. Examples are Brazil, Russia, India, and China (BRIC), Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Turkey (MINT). These regimes lack legal institutions that deter managerial rent protection. East Asian corporations provide another example of rent protection. More than two-thirds of East Asian corporations are under a single shareholder’s direction, and this dominant shareholder is usually a family group (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000: 82-84, 94, 110). In contrast, concentrated stock ownership is likely to wane in countries that have robust legal rules and institutions in place to curtail private benefits of control (Bebchuk, 1999: 3-4, 37).

Private benefits of control are usually higher in corporations that do not cross-list their securities abroad (Doidge, 2004; Reese and Weisbach, 2002; Doidge, Karolyi, Lins, Miller, and Stulz, 2009). When private benefits of control are large, corporate insiders face incentives not to subject the corporation to stricter disclosure rules and other listing requirements. Incumbents would retain a lock on control if the probable gain in the present value of cross-listing abroad falls short of the likely loss in private benefits of control. To the extent that private benefits of control create perverse incentives for incumbents to keep a lock on control by holding large equity blocks, the rent-protection theory suggests that cross-country differences in corporate ownership and governance are likely to persist over time.

In contrast to the neoclassical hypothesis that a corporation is a nexus of contracts between shareholders and incumbents, the team production theory suggests that a corporation can be viewed as a nexus of firm-specific investments (Blair and Stout, 1999: 247, 275). This theory suggests that a corporation is normally structured to promote stakeholder value instead of shareholder wealth. Each team member devotes highly specialized and irrevocable effort to corporate affairs. Employees carry out day-to-day operational tasks and assignments. Executives organize and oversee employee performance. Creditors and stock owners inject capital to support the corporation’s investment projects. As a hierarchical intermediary, the board of directors integrates all these endeavors to make the whole bigger than the sum of the parts (Rajan and Zingales, 1998). Each team member’s expertise has little value outside the joint enterprise, and nobody leaves this enterprise and realizes the value of his or her investment in full.

The above observation suggests that the individual investments are all complementary in nature. In the corporate context, the status quo tends to be one of multiple optima. If large adjustment costs are required for a corporation to move to an alternative optimum, continuance is often efficient (Bebchuk and Roe, 1999: 139-142). Hence, the extant ownership and governance patterns are only second-best options. For instance, Russian investors may prefer government control of large corporations because few legal rules protect shareholder rights. In this case, government control is a second-best option and thus serves as an alternative form of investor protection in Russia (Frye and Shleifer, 1997; Shleifer and Treisman, 2005). If a structural shift toward first-best structures (such as less government control with better legal protection of shareholder rights) requires substantial adjustment costs and then leads to third-best outcomes, it may be better to maintain the status quo. This rationale suggests that complementary corporate ownership and governance structures are likely to persist over time.

Social norms of fairness and trust help shape the path of corporate ownership and governance structures (Blair and Stout, 2001; Coffee, 2001; Licht, 2001). In corporate governance, the rules of the game often depend on what is perceived to be fair. Stakeholders view a peculiar distribution of corporate wealth and power as unfair if this distribution departs substantially from the terms of a reference transaction, which is the transaction that defines the benchmark for corporate interactions (Jolls, Sunstein, and Thaler, 1998). Due to cultural differences, the reference transaction may vary from country to country. For instance, American culture typically resists hierarchy and centralized authority more than French culture (Bebchuk and Roe, 1999: 168-169). Codetermination reflects the need for a fair go for employees in Germany (Roe, 1993: 1942-1943). Political connections matter a great deal to Chinese CEOs in several major corporate decisions, whereas, these connections generally have a negative effect on corporate performance in terms of post-IPO earnings growth, sales growth, or profit margin (Fan, Wong, and Zhang, 2007). In East Asia, some large corporations often find it necessary to bribe senior bureaucrats to seek protection in the form of exclusive trade rights, commercial privileges, and preferential government contracts (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000). Also, several East Asian and Italian large corporations regard family involvement as an indispensable value driver (Claessens, Djankov, and Lang, 2000: 82-84; Licht, 2001). All of these social norms of fairness set the informal reference transactions or rules of the game. These informal rules create certainty for stakeholder interactions.

Firm-specific fairness norms help enhance the corporation’s efficiency due to more cooperation and less opportunism among its stakeholders (Cooter and Eisenberg, 2000). The gradual internalization of fairness norms incentivizes stakeholders to trust one another in the nexus of firm-specific investments (Blair and Stout, 2001: 1807-1810). How willing stakeholders are to trust others shapes the initial ownership and governance arrangements in the corporate context (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, Shleifer, and Vishny, 1997b). Nevertheless, trust per se does not necessarily facilitate Berle-Means convergence. Because there can be substantial heterogeneity in social norms of fairness and trust, what is viewed as fair in Japan may not be equally fair in Australia, and similarly, German codetermination may not be a suitable solution to the agency problem that New Zealand corporations face. To the extent that social norms of fairness and trust diverge from country to country, this divergence suggests that corporate ownership and governance structures may continue to differ over time.

Synthesis and summary

The literature review has framed both sides of the debate on Berle-Means convergence. The neoclassical hypothesis and the path-dependence story both have their merits and thus need not be viewed as mutually exclusive. While the path dependence story suggests that the level of incumbent stock ownership concentration at any point in time depends on the initial condition, this static relation may not constitute the full picture. The neoclassical hypothesis may better describe the dynamic part of the picture that multinational corporations can adhere to higher standards of corporate governance by cross-listing their stocks abroad, by diversifying their portfolios via cross-border mergers and acquisitions, or by self-regulating corporate affairs in the presence of dispersed incumbent stock ownership. In light of this synthesis, we seek to develop a mathematical model to integrate both sides of the Berle-Means debate to depict a more holistic picture.

For complete details, the reader can delve into the full pre-print research article available on our AYA fintech network platform:

https://ayafintech.network/library/corporate-ownership-governance/

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

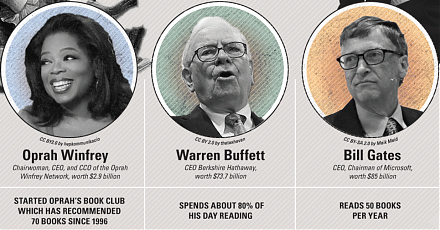

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2023-12-09 08:28:00 Saturday ET

International trade, immigration, and elite-mass conflict The elite model portrays public policy as a reflection of the interests and values of elites. I

2019-04-30 07:15:00 Tuesday ET

Through our AYA fintech network platform, we share numerous insightful posts on personal finance, stock investment, and wealth management. Our AYA finte

2023-04-28 16:38:00 Friday ET

Peter Schuck analyzes U.S. government failures and structural problems in light of both institutions and incentives. Peter Schuck (2015) Why

2019-07-25 16:42:00 Thursday ET

Platforms benefit from positive network effects, scale economies, and information cascades. There are at least 2 major types of highly valuable platforms: i

2023-08-28 08:26:00 Monday ET

Jared Diamond delves into how some societies fail, succeed, and revive in global human history. Jared Diamond (2004) Collapse: how societies

2019-01-09 07:33:00 Wednesday ET

Apple revises down its global sales revenue estimate to $83 billion due to subpar smartphone sales in China. Apple CEO Tim Cook points out the fact that he