2023-11-14 08:24:00 Tue ET

treasury deficit debt employment inflation interest rate macrofinance fiscal stimulus economic growth fiscal budget public finance treasury bond treasury yield sovereign debt sovereign wealth fund tax cuts government expenditures

Thomas Sowell (2019)

Discrimination and economic inequality

Thomas Sowell delves into how economists mull over the root causes of disparities in socioeconomic outcomes. In a negative light, Sowell cautions against particular government intervention in support of lower economic inequality. This government intervention may often inadvertently lead to negative consequences in the form of worse economic inequality in both wealth creation and income distribution. Several economic theories and policies can help move our global society toward equitable socioeconomic outcomes.

Thomas Sowell considers the common sources of economic inequality. In light of greater government intervention, Sowell first points out that not all inequality arises from discrimination. Sowell provides examples of how misattributing disparities to discrimination can result in subpar government intervention with wider disparities. Sowell further suggests that the government should stop trying to intervene in new markets. Here the government should allow the invisible hand of market forces to reduce economic inequality to efficient levels in the long run.

Sowell defines 3 key types of discrimination that can lead to disparities in economic outcomes. First, some discrimination sorts individuals accurately in light of relevant characteristics. Racial profiles often lead racial disparities in economic outcomes, and several other qualifications include gender, education, work history, and so on. Second, some discrimination sorts people on the basis of average group profiles. This statistical discrimination can often help gather enough information on relevant characteristics such as skills, risks, and information costs. Third, some taste-driven discrimination (or animus) occurs when decision-makers care about race itself but not race as a proxy for something else. Economists typically model this animus or taste discrimination as a cost to the decision-maker when he or she interacts with a person of color. The employer may derive negative utility from this interaction. In practice, Sowell compares and contrasts the uneven distribution of (un)favorable economic outcomes in the human population to the uneven distribution of natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and tornadoes etc. Economic success often requires many prerequisites such as effort, intelligence, education, practice, and life experiences in countries and places with good inclusive institutions.

Sowell cannot rule out the second and third types of discrimination, and he spends much time arguing that most disparities emerge from the first type of discrimination. Banks, employers, and universities etc apply this first type of discrimination to sort applicants into specific groups with relevant characteristics. These characteristics include race, gender, education, work history, many other qualifications, and so on. These differences in economic opportunities cannot result from both the fault and responsibility of schools, employers, and other institutions. Also, these differences in economic opportunities are not natural disasters either. The government should direct us to address childhood disparities as the root causes of adult disparities. In practice, neglecting this public policy implication serves only to deny our power to change the status quo. Understanding those causes of racial and other disparities is key for designing effective economic policies that can shrink those disparities in due course.

It is worth considering how and why discrimination persists in competitive markets. Many economists are familiar with the Becker model of taste-driven discrimination (Becker, 1957). This model predicts that most fair employers can take advantage of the prejudice of unfair employers to hire Black workers with lower wages and so higher profits as long as there are a sufficient number of fair employers in society. Over time, these fair employers drive unfair employers out of business. The racial gap in pay shrinks and disappears in due course. Variations in this Becker model can produce persistent racial disparities in wages and job opportunities (Charles and Guryan, 2011; Lang and Lehmann, 2012).

Adding search costs to new models of the recruitment process can further produce persistent disparities in wages and job opportunities. If even a few unfair employers exist in the labor market and it is costly to search for better job opportunities, Black job seekers may tend to accept lower reservation wages. These lower reservation wages lead Black job seekers to accept less desirable job offers. In turn, this labor recruitment process incentivizes fair employers to offer Black job candidates lower wages too. In equilibrium, racial disparities persist and result from this recruitment process. As a consequence, racial disparities can eventually result in sub-optimal investments in human capital accumulation. The recruitment biases can contribute to persistent and inefficient disparities that free market forces alone cannot shrink in due course.

In the academic job market specifically, high search costs suggest that even a few unfair employers can cause persistent disparities in pay and employment, even if there are no disparities in publication or other observable output. Several empirical studies show that women are held to higher standards in academic research output. Top journal articles by women tend to attract more citations than similar papers by men. In this positive light, these top journal articles by women are more meaningful and more significant contributions to the academic literature (Card and DellaVigna et al, 2020). From time to time, referees and editors push female authors to write more clearly than male authors in order to defend their ideas. This gender gap in writing quality widens over academic careers. Women respond by spending more time investing in this skill (whereas, men do not need to make this time investment). This tendency often lengthens the time for female authors to publish each research article. As a result, this common trend reduces the likelihood of tenure for women on the margin.

Many economic disparities arise from the other types of discrimination (statistical discrimination and taste discrimination (animus)). For instance, ban the box (BTB) policies prohibit employers from asking a prospective job applicant about his or her criminal record until late in the recruitment process. Each employer can run some background check before the employer hires the person. But then each employer has to justify each decision not to hire the job applicant if his or her criminal record is worrisome. From time to time, BTB policies cannot change employer concerns about hiring someone with a criminal record. By design, BTB policies now make it more costly to differentiate between otherwise-similar applicants with and without criminal records. After BTB policies come into effect, employers need to go through the full interview process with each job applicant, and make a conditional job offer before these employers ascertain whether the applicant has a criminal record that the employer perceives as worrisome. At that stage, if employers decide not to hire a job applicant due to his or her criminal record, these employers risk legal scrutiny of the decision of non-recruitment.

Ban the box (BTB) policies incentivize some job applicants without criminal records to get an occupational license that is off-limits to people with some convictions. In this way, these job applicants buy back the box that legislators ban in due course (Blair and Chung, 2018). As Sowell argues in the broader context of labor markets, the government often has to consider the likely endogenous behavioral response to any policy change.

The ripple effects of BTB highlight important economic problems with how our legal system currently tries to reduce discrimination and inequality. Courts often choose to consider evidence of a disparate adverse impact on minority groups to suffice to ban the use of particular information (such as criminal records) in the recruitment process. This current disparate-impact standard may cause more harm than good. Banning the use of information due to its disparate impact on a particular minority group may effectively broaden the discrimination to that entire group. When push comes to shove, the law of inadvertent consequences counsels caution.

Many policies remain in place not because they are effective but because they are politically convenient. Free markets often produce inefficient economic outcomes. In this case, government intervention can help enhance both equity and efficiency. Market failures occur from time to time due to information asymmetries, network effects, and externalities etc. Government intervention may not always be the right answer. However, government intervention plays an important role in numerous economic reforms and remedies etc, often in conjunction with free market forces, rather than in opposition to them.

Several studies delve into the effects of gender quotas in political representation. Requiring more women on the ballot both increases the representation of women in electoral office and then increases the average quality and competence of public leaders without evidence of any backlash from voters. Despite pervasive concerns, quotas do not lead to less competent women in office just because of their gender. In practice, female public leaders are as competent as most public leaders before the government introduces gender quotas for political representation. At the same time, these gender quotas can help increase average quality by crowding out less competent men (Besley et al, 2017). Increasing female representation further has long-term benefits in terms of changing voter views of female leaders in a positive light. With gender quotas, men experience female leadership, update their views about women as leaders, and improve their ability to screen female candidates on competence. As a result, gender quotas can help reduce reliance on gender-driven statistical discrimination. Moreover, gender quotas expand the pool of women for public leadership positions (O’Brien and Rickne, 2016). Female leaders can share their longer-run career aspirations and educational experiences with younger girls in accordance with the role model effect (Beaman et al, 2012). As these empirical examples suggest, sometimes government reforms and remedies that help reduce economic disparities often result in more efficient social outcomes because these reforms and remedies correct market failures.

With good intentions, politicians and technocrats can design new policies to correct market failures. Due to information asymmetries, externalities, and network effects etc, market failures often lead to inefficient economic outcomes. At the same time, incentives often affect human behaviors and social interactions. How do all these market players respond to economic reforms and remedies (in light of their extant preferences and incentives)? Instead of resigning ourselves to the mercy of market forces, politicians and technocrats can harness those market forces and incentives to create a more equitable world.

Thomas Sowell delves into how economists mull over the root causes of disparities in socioeconomic outcomes. In a negative light, Sowell cautions against particular government intervention in support of lower economic inequality. This government intervention may often inadvertently lead to negative consequences in the form of worse economic inequality in both wealth creation and income distribution. Several economic theories and policies can help move our global society toward equitable socioeconomic outcomes.

Thomas Sowell considers the common sources of economic inequality. In light of greater government intervention, Sowell first points out that not all inequality arises from discrimination. Sowell provides examples of how misattributing disparities to discrimination can result in subpar government intervention with wider disparities. Sowell further suggests that the government should stop trying to intervene in new markets. Here the government should allow the invisible hand of market forces to reduce economic inequality to efficient levels in the long run.

Sowell defines 3 key types of discrimination that can lead to disparities in economic outcomes. First, some discrimination sorts individuals accurately in light of relevant characteristics. Racial profiles often lead racial disparities in economic outcomes, and several other qualifications include gender, education, work history, and so on. Second, some discrimination sorts people on the basis of average group profiles. This statistical discrimination can often help gather enough information on relevant characteristics such as skills, risks, and information costs. Third, some taste-driven discrimination (or animus) occurs when decision-makers care about race itself but not race as a proxy for something else. Economists typically model this animus or taste discrimination as a cost to the decision-maker when he or she interacts with a person of color. The employer may derive negative utility from this interaction. In practice, Sowell compares and contrasts the uneven distribution of (un)favorable economic outcomes in the human population to the uneven distribution of natural disasters such as earthquakes, hurricanes, and tornadoes etc. Economic success often requires many prerequisites such as effort, intelligence, education, practice, and life experiences in countries and places with good inclusive institutions.

Sowell cannot rule out the second and third types of discrimination, and he spends much time arguing that most disparities emerge from the first type of discrimination. Banks, employers, and universities etc apply this first type of discrimination to sort applicants into specific groups with relevant characteristics. These characteristics include race, gender, education, work history, many other qualifications, and so on. These differences in economic opportunities cannot result from both the fault and responsibility of schools, employers, and other institutions. Also, these differences in economic opportunities are not natural disasters either. The government should direct us to address childhood disparities as the root causes of adult disparities. In practice, neglecting this public policy implication serves only to deny our power to change the status quo. Understanding those causes of racial and other disparities is key for designing effective economic policies that can shrink those disparities in due course.

This analytic essay cannot constitute any form of financial advice, analyst opinion, recommendation, or endorsement. We refrain from engaging in financial advisory services, and we seek to offer our analytic insights into the latest economic trends, stock market topics, investment memes, personal finance tools, and other self-help inspirations. Our proprietary alpha investment algorithmic system helps enrich our AYA fintech network platform as a new social community for stock market investors: https://ayafintech.network.

We share and circulate these informative posts and essays with hyperlinks through our blogs, podcasts, emails, social media channels, and patent specifications. Our goal is to help promote better financial literacy, inclusion, and freedom of the global general public. While we make a conscious effort to optimize our global reach, this optimization retains our current focus on the American stock market.

This free ebook, AYA Analytica, shares new economic insights, investment memes, and stock portfolio strategies through both blog posts and patent specifications on our AYA fintech network platform. AYA fintech network platform is every investor's social toolkit for profitable investment management. We can help empower stock market investors through technology, education, and social integration.

We hope you enjoy the substantive content of this essay! AYA!

Andy Yeh

Chief Financial Architect (CFA) and Financial Risk Manager (FRM)

Brass Ring International Density Enterprise (BRIDE) ©

Do you find it difficult to beat the long-term average 11% stock market return?

It took us 20+ years to design a new profitable algorithmic asset investment model and its attendant proprietary software technology with fintech patent protection in 2+ years. AYA fintech network platform serves as everyone's first aid for his or her personal stock investment portfolio. Our proprietary software technology allows each investor to leverage fintech intelligence and information without exorbitant time commitment. Our dynamic conditional alpha analysis boosts the typical win rate from 70% to 90%+.

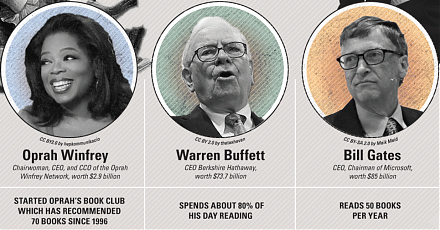

Our new alpha model empowers members to be a wiser stock market investor with profitable alpha signals! The proprietary quantitative analysis applies the collective wisdom of Warren Buffett, George Soros, Carl Icahn, Mark Cuban, Tony Robbins, and Nobel Laureates in finance such as Robert Engle, Eugene Fama, Lars Hansen, Robert Lucas, Robert Merton, Edward Prescott, Thomas Sargent, William Sharpe, Robert Shiller, and Christopher Sims.

Follow our Brass Ring Facebook to learn more about the latest financial news and fantastic stock investment ideas: http://www.facebook.com/brassring2013.

Follow AYA Analytica financial health memo (FHM) podcast channel on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCvntmnacYyCmVyQ-c_qjyyQ

Free signup for stock signals: https://ayafintech.network

Mission on profitable signals: https://ayafintech.network/mission.php

Model technical descriptions: https://ayafintech.network/model.php

Blog on stock alpha signals: https://ayafintech.network/blog.php

Freemium base pricing plans: https://ayafintech.network/freemium.php

Signup for periodic updates: https://ayafintech.network/signup.php

Login for freemium benefits: https://ayafintech.network/login.php

If any of our AYA Analytica financial health memos (FHM), blog posts, ebooks, newsletters, and notifications etc, or any other form of online content curation, involves potential copyright concerns, please feel free to contact us at service@ayafintech.network so that we can remove relevant content in response to any such request within a reasonable time frame.

2020-09-24 10:26:00 Thursday ET

Edge strategies help business leaders improve core products and services in a more cost-effective and less risky way. Alan Lewis and Dan McKone (2016)

2018-02-01 07:38:00 Thursday ET

U.S. senators urge the Trump administration with a bipartisan proposal to prevent the International Monetary Fund (IMF) from bailing out several countries t

2019-07-11 10:48:00 Thursday ET

France and Germany are the biggest beneficiaries of Sino-U.S. trade escalation, whereas, Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan suffer from the current trade stando

2018-10-25 10:36:00 Thursday ET

Trump tariffs begin to bite U.S. corporate profits from Ford and Harley-Davidson to Caterpillar and Walmart etc. U.S. corporate profit growth remains high a

2019-11-15 13:34:00 Friday ET

The Economist offers a special report that the new normal state of economic affairs shines fresh light on the division of labor between central banks and go

2019-04-30 07:15:00 Tuesday ET

Through our AYA fintech network platform, we share numerous insightful posts on personal finance, stock investment, and wealth management. Our AYA finte